Catching Archive Fever: Delving Into August Sander’s Archive

Elizabeth Smith

To cite this contribution:

Smith, Elizabeth. ‘Catching Archive Fever: Delving Into August Sander’s Archive’ . Currents Journal Issue One (2020), https://currentsjournal.net/Catching-Archive-Fever.

Download this article ︎︎︎EPUB ︎︎︎PDF

Course of study:

Bachelor of Arts (Honours) in History of Art, University of Western Australia

Keywords:

Archives; institutions; collections; art history; institutional critique; truth

Abstract:

Encompassing his entire career, August Sander’s photographic portraiture project People of the Twentieth Century remained unfinished at his death in 1964. Since then, this project and his archive of photographs has passed onto family and institutions. 24 collections across the world can claim to have a piece of the photographer’s work. Drawing on Derrida’s ‘Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression,’ this essay investigates the art historical practice taking place within Sander’s work. Even as institutions are devoted to communicating and preserving legitimacy and truth, this essay proposes how unstable those sentiments are. Can art history find a way to engage with its subject matter that opens the tradition out into the future?

August Sander, People Of The 20th Century (Seven Volume Set). Published by Harry N. Abrams, NY (2002) to mark the 125th anniversary of the photographer's birth. The set consists of Volume I: The Farmer; Volume II: The Skilled Tradesman; V olume III: The Woman; Volume IV: Classes and Professions; Volume V: Th e Artists; Volume VI: The City and Volume VII: The Last People.

In order to summon a cross-section of our time and of the German people, I’ve collected these photographs in portfolios and, in doing so, I’m starting with farmers and ending with representatives of the cultural aristocracy…Using absolute photography to frame the individual classes as well as their surroundings, I hope to provide a true psychology of our time and of our people.1

In this letter to the photography expert and collector Erich Stenger,2 August Sander (1876-1964) outlines the initial conceptions for an archive of photographic portraits of his contemporaries, the Menschen des 20. Jahrhunderts [People of the Twentieth Century]. This project eventually encompassed Sander’s entire career, and its scope and arrangement continue to attract a considerable amount of scholarship. The scope of this essay extends to the institutions that hold Sander’s work, specifically how People of the Twentieth Century is treated by various institutions and collections. But it also wants to leave the reader with a specific understanding of the archive, which is signposted throughout. The art historical practice taking place within Sander’s work, including at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, is rendered problematic at a conceptual level, which will be explicated in the following pages. Can art history find a way to engage with its subject matter that opens the tradition out into the future?

The word ‘archive’ has a very practical meaning as ‘a place where historical documents or public records are kept.’3 By extension, the archive is also a kind of prosthetic for memory, or a way to structure it. An archive allocates memory to an external place for protection, which creates the possibility to repeat and reproduce the archive because memory has now become tangible and systematised.4 In his 1995 text, “Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression”, Jacques Derrida proposed that the archive is unstable even as it is devoted to methodologies of communicating and preserving the truth, including how truth operates in this institution in a way that has legitimate meaning for those who use it.

As Carolyn Steedman points out in her text “Something She Called a Fever: Michelet, Derrida, and Dust (Or, in the Archives with Michelet and Derrida)” (2006), the arkhé is ‘inextricably bound up with the authority of beginnings.’5 This authority is described briefly in Derrida’s explanation of the operation of the Greek city-state, and where the documents were kept at the arkheion, the residence of the superior magistrate.6 Derrida’s titular fever, trouble, or sickness of the archive is ‘to do with its very establishment, which is the establishment of state power and authority.’7 Fever manifests itself in two ways. Fever first suggests a feeling of madness or disorder, a death drive or destruction drive. Effectively, the archive relies on this madness and the death drive to stabilise itself. The archive deals with the madness by putting to death that which does not correspond to it. In other words, it needs to have a selective memory and forget about what lies outside the archive. It annihilates live memory and seeks to order it under a systematic rationale. This destruction drive allows the archive to protect itself from external elements and to police its own borders, making it more readable for those who are using the archive.8 On the other hand, fever also denotes a need, ‘a burning with passion’9 for the archive. It signals:

an irrepressible desire to return to the origin, a homesickness, a nostalgia for the return to the most archaic place of absolute commencement.10

This kind of fever denotes a longing for the original archive; not the physical or external archive, but the origin point which lies before the archive and the point at which an archive could be constructed. This is the archive as authority bound up with the law, and, as a type of pathology, determining a history and discipline of ideas itself.

Keeping Derrida’s sense of the archive in mind, how can we now understand the portrait photographs of August Sander? This essay will consider People of the Twentieth Century as archival in form as well as in process. Specifically, it will be looking at the many reconstructions and reinterpretations of Sander’s project as well as its place within various family and museum collections. Derrida’s work can potentially shed new light on the project as it explores the psyche of archives, their makers, and their caretakers. It destabilises the mechanism of truth commonly bound to archives and reveals the delicate work that goes into constructing a ‘legitimate’ archival document. Most importantly, considering Sander’s work in Derrida’s sense of archiving can offer new scope for interpretation and thereby capture the continued magnetism and relevance of the project.

Sander organised his portraits with an implied hierarchy into occupational, social, and family arrangements so as to reflect the various elements of society and nominated seven categories: The Farmer, The Skilled Tradesman, The Woman, Classes and Professions, The Artists, The City, and The Last People. These seven groups, in turn, were subdivided into forty-five portfolios, with each portfolio illustrating a typological theme, such as Portfolio 12: The Technician and Inventor or Portfolio 19: The Scholar. In total, between 500 and 600 photographs formed part of the work.11 As the author of the project, Sander is the archon or keeper of the archive. According to Derrida, there is always more than one archon, but Sander inhabits the place of first archon or archivist:

The first archivist institutes the archive as it should be… not only in exhibiting the document, but in establishing it.12

Therefore, Sander is responsible for the order that People of the Twentieth Century will take, what photographs will be included, and the documents that are not appropriate and must be excluded from the project.13 Such exclusions in the first instance constituted photographs that were not portraits.

Sander chose ‘familiar visual grammars’14 such as a defined horizon line and a clear demarcation between foreground and background to make his portraits more legible and thus more suited to function as alleged objective documents of his time. Sander’s approach to taking photographs and staging his sitters is illustrated in a lecture he gave in 1931, entitled “Photography as a Universal Language”,

One can snap a shot or take a photograph; “to snap a shot” means reckoning with chance, and “to take a photograph” means working with contemplation —that is to comprehend something, or to bring an idea from a complex to a consummate composition.15

This contemplation that Sander speaks of references his consistent use of long exposure times lasting up to ten seconds,16 but also as a demand on his sitters to contemplate their engagement with the photo-taking process, stopping their activity and ‘assuming the pose they felt best represented their occupation for the camera.’ This approach reinforced Sander’s vision of producing trustworthy types and a ‘truthful’ document of the time.

In establishing the order of People of the Twentieth Century, the individual portraits are separate objects which have typological order imposed on them. Each sitter is named according to their trade, class, or profession. They are then subjected to a process of repetition and serialisation by being placed in a portfolio with other portraits, bound together under an overarching typological theme. These typological themes are then distributed across the seven volumes. As a result, Sander’s subjects’ transition from individuals to types, shedding their differences for unifying commonalities to achieve a complete and total portrait of the time. Sander’s method for organising his portraits in People of the Twentieth Century is ‘architectural,’17 building a typology ‘from individuals to portraits of couples and from there to portraits of families or clubs.’18 There is a uniformity in the presentation of each subject ‘usually shown in the environ of his work or life situation, and most are displayed in full-length or three-quarter portraits, always in a serious mood.’19 This repetitiveness apparent in Sander’s project signals a construction around a common theme and a ‘rhythm of accumulation’20 of knowledge.

However, for the typological portfolios to work, the viewer must forget or put to death the memory of something which lies outside the typology. In other words, the viewer must forget that they are individuals to effectively consume the unifying order and the overall archival typological framework of People of the Twentieth Century. Sander’s goal is to order and make tangible the objective fact of society through portraiture. By assigning roles to individuals, this unifies the viewer in understanding a system of meaning and truth instead of experiencing ambivalence and possible misidentification.

Sander had taken all photographs for the project before World War II and stopped producing new portraits in favour of searching instead, through his archives for images which might fill the gaps.21 He published two much abbreviated versions of People of the Twentieth Century: its initial manifestation, the photobook Face of Our Time (1929), and a second version, Deutschenspiegel, appeared shortly before his death.22 At eighty portraits, the Deutschenspiegel remains the most complete iteration of People of the Twentieth Century authorised by Sander himself.

Sander, as first archon, established the archive of People of the Twentieth Century according to his vision for a collection of portrait photographs depicting types illustrating the changing times. His studio (the arkheion) is where the project was organised. The arkheion is not a fixed location, but it is the residences at which that Sander worked in to construct People of the Twentieth Century throughout his career. The arkheion ‘marks this institutional passage from the private to the public, which does not always mean from the secret to the non-secret.’23 It marks where the photographs for Face of Our Time and Deutschenspiegel have passed through for public consumption. However, upon Sander’s death, the arkheion passed on to another institution—his family—who initially took on the role of interpreting and safeguarding his visual and written documents. The family adopted Sander’s organising principles for People of the Twentieth Century, as they sought to complete and publish his project in its entirety, thereby opening it to the public for consumption. Their actions, however, also opened the archive up to be unravelled now it was no longer in Sander’s hands.

In 1973, Sander’s son Gunther Sander published Men Without Masks: Faces of Germany 1910-1938, a selection of 230 portraits and oddly—considering the title of the publication—six landscapes taken by his father between 1910 and 1938. This book does not have the express purpose of reconstructing People of the Twentieth Century. Rather, it is an introduction to Sander, his life, and his career. The inclusion of a foreword by Golo Mann follows the structure of Face of Our Time which had included an essay by the writer Alfred Doeblin. Instead of the seven volumes as outlined by Sander for People of the Twentieth Century, Gunther Sander distributed the 230 photographs into five categories: Archetypes, Country Folk, Trades, Classes and Professions, Life, and Transience. While Gunther Sander attempted to organise each category into a portfolio structure, he only managed this in two of the categories: Trades, Classes and Professions which contains three portfolios, and Transience containing two. There is no specified number in each category. In Trades, Classes and Professions the first portfolio contains twenty-seven portraits, and the second portfolio contains fifty-nine. Gunther Sander prefaces each category with the labels of the portraits included in that category, but these labels are not included with the photographs. This suggests that the reader will have the labels as a guide but be able to pick out the different types simply by looking at the portraits.

The photographs are presented on different scales: some share a page, others are assigned their own page, while yet others spread across two pages. This messy arrangement seems completely arbitrary across each category. Yet, it also suggests a greater importance to some images than others, something which would have run contrary to the seriality and equal status implied in Sander’s original conception. As a result, the opportunity for order is severely diminished. Another editorial decision made by Gunther Sander was to present the photographs uncropped. For example, in Face of Our Time, the portrait of the jobless man focuses on the man’s features. Gunther Sander, in Men Without Masks includes the same photograph uncropped [see Fig. 1 and Fig. 2]. A harmless change intended to provide ‘the maximum of visual information’24 undoes the potential considerations made by Sander himself for organising the project. Furthermore, Gunther Sander was the first to identify and name Sander’s sitters, restoring the portrayed to an individual state and reducing their status as type. This was, of course, easiest to achieve in the case of publicly known figures, such as writers, musicians, or artists, such as Willi Bongard and Gottfried Brockmann, whom Sander had captioned Bohemians 1922-25 in Face of Our Time and People of the Twentieth Century. [Fig. 3] By labelling the same portrait ‘The Painters Gottfried Brockmann and Willi Bongard, 1924’ in his edition, Gunther Sander exposes his father’s work to an investigative process in which individuals stand in as overarching representatives for explaining August Sander’s People of the Twentieth Century as a whole, and thereby significantly weakens its serial structure, which loses necessity and significance. In his biography, Gunther Sander reveals himself to have been his father’s assistant, often present in meetings about the project:

My father refused to be influenced as to the arrangement of the work, however, and he only accepted concrete suggestions concerning possible subjects on the condition that the persons in question should appear without name or title. He wanted the photographs themselves to express what was missing in verbal descriptions and details.25

This demonstrates that Sander’s son was aware of Sander’s intentions for the project yet acted against his father’s principle of not naming sitters in the reconstruction. Overall, Gunther Sander’s early reconstruction of People of the Twentieth Century is not easily accessible, as it leaves the viewer overwhelmed with content and few organising prompts. The whole project, one might argue, is rendered unstable here. We can think of Gunther Sander as another archon or archivist who not only had the power to guard Sander’s documents, he also had the right to interpret them for the ‘operation of a system of law.’26 In other words, Gunther Sander decided how Sander’s work was to be read by the public.

The second version differs markedly. Published in 1986 and entitled August Sander: Citizens of the Twentieth Century: Portrait Photographs 1892-1952, it is a reconstruction of the project compiled from Sander’s notes and annotations by Gunther Sander in collaboration with Ulrich Keller, an art history professor from the University of California. In one large volume, it presented 431 portraits contained in forty-five portfolios, divided into seven sections, prefaced with an introductory essay by Keller which discusses Sander’s methods and the development of the project.27

In 1992, Sander’s entire oeuvre was purchased by the SK Stiftung Kultur der Sparkasse Koeln/Bonn, a cultural foundation in Cologne.28 As caretaker of the archive, it is ‘responsible for the academic research of Sander’s work and ensuring its public accessibility and posterity lending works to museums and managing reproduction rights in… publications.’29 The foundation contains the largest and most complete collection of Sander’s archive as a whole, comprising ‘10,700 original negatives, some 3,500 vintage prints, original correspondence, Sander’s private library as well as furniture, and parts of his photographic equipment.’30 In 2002, Susanne Lange, director of the photography collection of the Stiftung Kultur, Gabriele Conrath-Scholl, a research associate for the photographic collection, and Sander’s grandson, Gerd Sander, published the next version of People of the Twentieth Century. This is the largest reconstruction, containing 619 portraits, 150 more than the 1986 version, and it claims to be the most faithful to Sander’s intentions, basing itself on careful research of his annotations on photographs and other written notes.31 Like the Keller and Gunther Sander collaboration, it presents the portraits in forty-five portfolios. However, the seven categories are themselves divided into seven separate volumes.

The layout of the new edition is outlined in the preface to the seven volumes. Editor, Susanne Lange notes four decisions that were made for this reconstruction, including the ‘conscious decision’ not to ‘limit the number of photographs systematically to 12 per portfolio.’ Lange justifies this decision based upon the fact that Sander made the specification to have 12 portraits only in the Portfolio of Archetypes but did not reinforce it in later portfolios. Secondly, by consulting Sander’s notations, this edition was able to assign over 200 negatives ‘unequivocally’ to their portfolios. Thirdly, the images were cropped ‘on the basis of the existing original photographs’ to ‘preserve the authentic interpretation of the image as laid down by Sander’s own cropping.’ Finally, they chose to match the layout of the publication Face of Our Time, which allows the viewer to see each image as a ‘separate image first of all, and then as part of a pictorial continuum.’ Lange justifies this on the grounds that Sander’s photographs embody an ‘individual expressiveness’ as well as a ‘typological quality.’32 The Cologne edition also includes the annotations that Sander made on some of his portraits at the beginning of each volume, such as the note ‘Self-portrait marking the start of my project,’33 which Sander annotated alongside his self-portrait in Portfolio 42: Types and Figures of the City [Fig. 4].

These decisions to use Sander’s annotations and previous publications as a guide, justify their aim to recreate the project as authentically as possible, according to Sander’s vision. However, individual names are again restored to sitters and this goes against Sander’s intentions, and subsequently disturbs this claim to authenticity. Furthermore, giving the reader access to Sander’s notes means information is layered onto some individual photographs and thereby disrupts their seriality as equal parts to a larger whole. While these discrepancies exist, this edition is also aimed to further scholarship, allowing others who might not normally be able to visit the Sander archive, to conduct research on the project. Ultimately, in this publication and Gunther Sander’s, these additions alter the nature of the project, giving the reader access to information that Sander would likely not have used if he had completed the project himself, exposing what Derrida calls, a secret to its order,34 effectively changing the function of the archive from Sander’s vision. They are interpreting Sander’s work though and giving it a system under which it could operate legibly and legitimately.

Finally, in 2015, the New York Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) joined efforts to reconstruct the People of the Twentieth Century following their acquisition of a ‘complete’ set from the Sander family in 2015, printed from negative glass plates between 1990 and 1999. This is currently underway in the form of symposiums, inviting scholars to speak on a singular portfolio of their choice.35 These efforts to publish the archive are also accompanied by efforts to curate the archive, undertaken by institutions around the world.

As Derrida indicates in his text, and as the multiple reconstructions of Sander’s project by his family, The Stiftung Kultur, or the MoMA collection illustrate, there is a feverish desire for the archive. Furthermore, as Carolyn Steedman elucidates, this desire is not only in operating or using the archive, but also in owning it.36

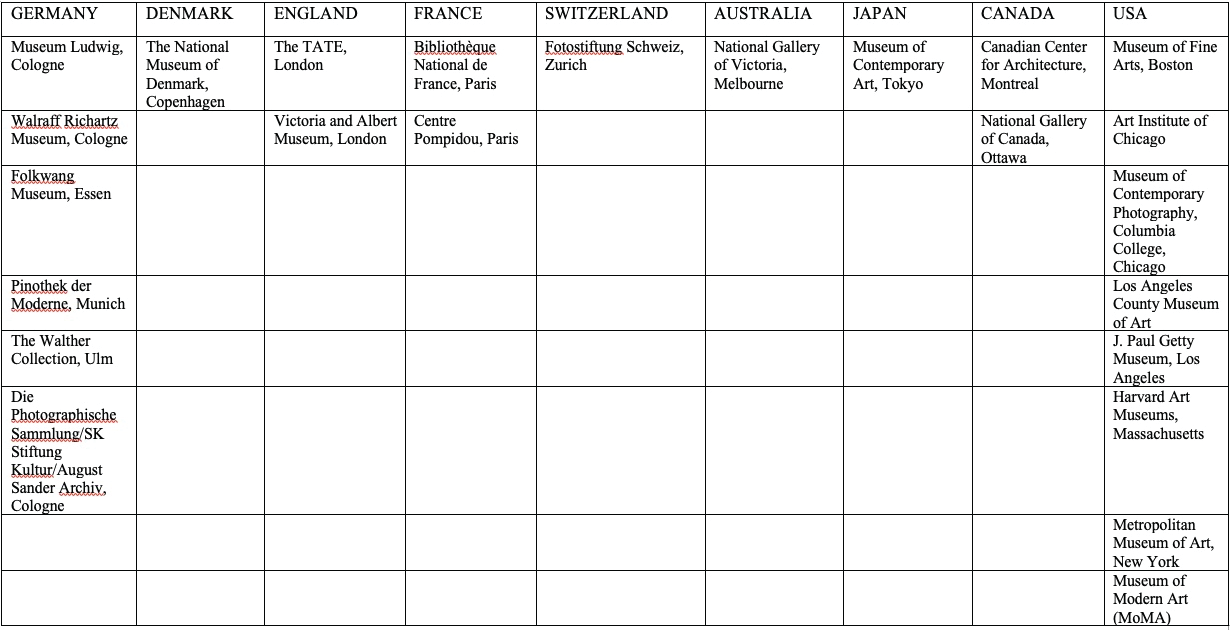

Currently, Sander’s work is held in about twenty-four collections. As a result, it now has as many arkheions or residences where his work is interpreted and used by several different archons. The list is as follows:

![]() 37

37

Each of these twenty-four collections house anywhere upwards of two photographs, (in the case of the Fotostiftung Schweiz in Switzerland)38 from People of the Twentieth Century. The largest collections can be found in four institutions across Europe and the United States: the Tate in London, The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles each own around 200 photographs, while MoMA now has the most with its recently acquired ‘complete’ set. Each collection is attracted to what could be termed a canonical group of Sander photographs that invariably includes images of Westerwald farmers or the Boxers, 1929 [Fig. 5]. And the attraction particularly of this last image is obvious: The Boxers have a theatrical presence, as the viewer consults the cheeky grin of the boxer on the right. It is not until the viewer looks down that they notice the shoelaces of the boxer on the left tied together and they can share in the joke. Yet, as a result, the original order of People of the Twentieth Century is often foregone for a collection of highlights which illustrates Sander’s career and artistic practice. It negates that People of the Twentieth Century was to be considered as a serial project, in which patterns and types take precedence, and which formed a distinct unit in Sander’s oeuvre. It is, at best, replaced with a new kind of seriality, one which conforms to a particular collection. So, for example, while the Harvard Museums has forty-nine photographs by Sander,39 and while these might build an understanding of Sander’s style, they cannot fully illustrate the intricate structure of the project. People of the Twentieth Century as a whole body of work is ontologically different across all institutions, meaning the way that viewers relate to these images is ‘determined by the form they assume in the various publications or exhibitions of his work, in which photographs… are ordered by editors, publishers, and curators.’40 Furthermore, the size of exhibition venues, as much as collection holdings or loan budgets usually condition such presentation of Sander’s project. Another example of how the archive is curated and how viewers relate differently to Sander’s archive is through the variation in titles of the photographs. Katherine Tubb highlights this variation in titles through the photograph of circus workers drinking tea.41 In the London Tate collection, the photograph is entitled Circus Workers, 1926-1932 [Fig. 6]. Yet, the MoMA collection calls it Indian Man and German Woman. These variations highlight how different collections interpret Sander’s photographs and change how the public relate to Sander’s images, emphasising the unrooted and unstable nature of People of the Twentieth Century as it stands today. Similarly, scholarship has frequently pointed out discrepancies contained within the overall project, honing in on the tendency of Sander’s types to move around, or to become what Miranda Wallace in her text “August Sander’s Photographic Archive: Fables of the Reconstruction” (2002), has termed ‘typologically mobile’.42 Austrian artist and writer, Raoul Hausmann, in “Raoul Hausmann as Dancer,” found in Portfolio 42: Types and Figures of the City, [Fig. 7] is one of the mobile figures. Firstly, because he is not a professional dancer, he is just modelling the role without being able to accurately fulfil that role outside of portfolio. Secondly, Hausmann also appears in various roles throughout the project. He is again featured as ‘Inventor and Dadaist’ in Portfolio 12: The Technician and Inventor, [Fig. 8] and once more standing between two women identified as Hedwig Mankiewitz and Vera Broïdo in parentheses, and entitled “The Dadaist Raoul Haussmann, 1929” in Portfolio 13: Woman and Man [Fig. 9]. This last portrait is extremely problematic for the order of types that Sander was constructing. It raises the question of whether Hausmann is cast in his role as a man or if his role is as he, Raoul Hausmann. As he is placed in a portfolio which looks specifically at these relationships between woman and man, the inclusion of Raoul Hausmann’s individual name in the title of the portrait upsets the transition to a type as it demonstrates his individuality rather than his gender. This problematises his place within the archive as an identifiable type, destabilising the technique of repetition which is supposed to stabilise the project.

Pointing out these discrepancies destroys the very fabric of the archive to construct order. It is not known if this was Sander’s intention. As Wallace points out:

These collecting and research practices have left People of the Twentieth Century not only fragmented, but open to considerable variation and interpretation by multiple cultural environments who decide which of Sander’s photographs justify or authenticate a particular experience of his work as a whole. As a result, the original authority of People of the Twentieth Century is lost, as its organising principles of seriality which helped to stabilise Sander’s project no longer function in these environments. As Derrida puts it, ‘what is no longer archived in the same way is no longer lived in the same way.’44

Hannah Shaw, a reporter for the most recent August Sander Project Symposium held at MoMA at the beginning of this year, finishes her report with some questions, most notably:

The question of how to get the most out of Sander lies at the heart of this essay. People of the Twentieth Century has a long legacy of interpretation and reconstruction and it seems fit to end on an analysis of its most recent and ongoing attempt at MoMA. Reading The August Sander Project webpage, the first paragraph not only reads that it was never completed, but that it ‘has never been exhibited in North America.’46 Furthermore, to celebrate this milestone, MoMA believes that a set of symposiums over a five-year period will demonstrate a

The investigative model that MoMA uses is based on the fact that a complete iteration of Sander’s works has never been exhibited in north America before. Furthermore, their deployment of various scholars to talk about Sander’s work repeat the same processes as those who have already engaged with his work and they also reveal the same inconsistencies as those who have previously undertaken scholarship on People of the Twentieth Century. Derrida believes that deconstruction is something healthy for institutions to go through as it is a means for their legitimacy and for their survival. This practice that MoMA is undertaking of looking at Sander’s work appears unable to uncover something new or interesting or different in four years’ worth of symposia. Moreover, these symposia at best, distribute a carefully curated survey of arguments and observations that have already been made about the work. How is MoMA as an institution giving People of the Twentieth Century more space to diversify and transform as a work other than the fact that it has never been exhibited in North America before? MoMA may be producing more content for People of the Twentieth Century, but if this work is so significant for the cultural value of MoMA’s modern art collection, its method of engagement is problematic. Its practices are suggestive of compartmentalising the project, not allowing it to grow and evolve.

Sander’s work in People of the Twentieth Century is kept safe and alive in multiple collections and through multiple reconstructions. However, it has also been exposed to the collections different ordering principles and additions through its reconstructions which destabilise the project’s original ordering principles. The way that collections across the world and the reconstructions have treated People of the Twentieth Century engages in an archive fever or ‘burning with passion.’48 In the case of the collections, they engage in a fever by having the desire to hold some of Sander’s work. This fragments the organising fabric of People of the Twentieth Century, establishing a different project all together. In the case of the reconstructions carried out by Sander’s son, Keller, and Lange and Conrath-Scholl from the Stiftung Kultur, Cologne, they serve a purpose of recreating the project, of following its organising principles. However, they are more skeptical of these ordering principles and as a result, have added to the work, individuals’ names, breaking down the structural memory that Sander had consigned to each individual when he chose to arrange them as types. By adding biographical details to the sitters, they are augmenting the very fabric of the People of the Twentieth Century as established by Sander. Starting with the individual portraits, Sander’s son, Keller, and Lange and Conrath-Scholl effectively undermine the system from its point of origin. These practices, it can be argued, are a form of deconstruction or critique of the project. They also add meaning to People of the Twentieth Century by interpreting it. They are potentially improving it and replacing the original with another. Derrida elucidates this:

The original People of the Twentieth Century may be rendered unstable by these choices, but it still means that its principles are being practiced and critiqued.

If we are going to uncover more about Sander’s work, if we want it to survive, we need to find a better way to engage with its fever, with its archival possibility. Sander’s work is not just incomplete, it is amorphous in nature. Are our institutions erasing that nature even, and especially in the process of producing it as a discernible work, as an archive of materiality? In other words, what do our institutions offer us when artwork enters into them? Are they giving artworks a space to breathe and be interpreted or are they closing them off, placing them in an archive to gather dust in the name of increasing a collections cultural value? That question is rendered ongoing from Derrida, Sander’s work, and the institutions themselves.

Figure details:

Please note, permission has not yet been granted to reproduce these figures so we have directed you to approximate reproductions online. We have noted when they have been catalogued differently.

Fig. 1: August Sander, Inmate of an asylum, 1926, Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur/August Sander Archiv, in August Sander and Gunther Sander, Men Without Masks: Faces of Germany 1910-1938 (Greenwich Connecticut, New York Graphic Society, 1973), 262. This figure is also viewable online at www.moma.org, catalogued under the alternative title Asylum Inmate.

Fig. 2: August Sander, Asylum Inmate, 1926-1930, Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur/August Sander Archiv, in Gabriele Conrath-Scholl and Susanne Lange, August Sander: People of the Twentieth Century, Volume 6: The City (Harry N. Abrams First Edition, 2002), 199. This figure is a cropped and more highly contrasted version of the above figure.

Fig. 3: August Sander, Bohemians, 1922-25, Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur/August Sander Archiv, in Gabriele Conrath-Scholl and Susanne Lange, August Sander: People of the Twentieth Century, Volume 6: The City (Harry N. Abrams First Edition, 2002), 185. This figure is also viewable online at www.moma.org, catalogued under the alternative title Bohemians [Willi Bongard and Gottfried Brockmann].

Fig. 4: August Sander, Photographer, 1925, Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur/August Sander Archiv, in Gabriele Conrath-Scholl and Susanne Lange, August Sander: People of the Twentieth Century, Volume 6: The City (Harry N. Abrams First Edition, 2002), 183. This figure is also viewable online at www.moma.org, catalogued under the alternative title Photographer [August Sander].

Fig. 5: August Sander, Boxers, 1929, Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur/August Sander Archiv in August Sander and Alfred Doeblin Antlitz der Zeit: sechzig Aufnahmen deutscher Menschen des 20. Jahrhunderts (Muenchen: Schirmer/Mosel, 1990), 43. This figure is also viewable online at www.moma.org.

Fig. 6: August Sander, Circus Workers/Indian Man and German Woman, 1926-1932, Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur/August Sander Archiv, in Gabriele Conrath-Scholl and Susanne Lange, August Sander: People of the Twentieth Century, Volume 3: The Woman (Harry N. Abrams First Edition, 2002), 71. This figure is also viewable online at www.moma.org, catalogued under the alternative title Indian Man and German Woman.

Fig. 7: August Sander, Raoul Hausmann as Dancer, 1929, Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur/August Sander Archiv, in Gabriele Conrath-Scholl and Susanne Lange, August Sander: People of the Twentieth Century, Volume 6: The City (Harry N. Abrams First Edition, 2002), 187. This figure is also viewable online at www.moma.org.

Fig. 8: August Sander, Inventor and Dadaist, 1929, Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur/August Sander Archiv, in Gabriele Conrath-Scholl and Susanne Lange, August Sander: People of the Twentieth Century, Volume 2: The Skilled Tradesman (Harry N. Abrams First Edition, 2002), 149. This figure is also viewable online at www.moma.org, catalogued under the alternative title Inventor and Dadaist [Raoul Hausmann].

Fig. 9: August Sander, The Dadaist Raoul Hausmann [with Hedwig Mankiewitz and Vera Broïdo], 1929, Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur/August Sander Archiv, in Gabriele Conrath-Scholl and Susanne Lange, August Sander: People of the Twentieth Century, Volume 3: The Woman (Harry N. Abrams First Edition, 2002), 49. This figure is also viewable online at www.moma.org.

Notes:

About the author:

Elizabeth Smith is a recent University of Western Australia graduate, receiving Honours in Art History in 2019. Over the past twelve months she has been developing her practice, including working with newly-formed, Perth-based artist-run-initiative, Pig Melon; has been part of Room01 Collective, an arts organisation which explores nascent arts practice in Western Australia; co-curated, with Aimee Dodds, the second iteration of Artsource’s (e)merging project; and, worked with The Lobby to develope an exhibition taking place in November 2020 as part of its emerging curatorial program. Liz hopes to continue to explore different opportunities within the arts as an independent curator and writer.

The layout of the new edition is outlined in the preface to the seven volumes. Editor, Susanne Lange notes four decisions that were made for this reconstruction, including the ‘conscious decision’ not to ‘limit the number of photographs systematically to 12 per portfolio.’ Lange justifies this decision based upon the fact that Sander made the specification to have 12 portraits only in the Portfolio of Archetypes but did not reinforce it in later portfolios. Secondly, by consulting Sander’s notations, this edition was able to assign over 200 negatives ‘unequivocally’ to their portfolios. Thirdly, the images were cropped ‘on the basis of the existing original photographs’ to ‘preserve the authentic interpretation of the image as laid down by Sander’s own cropping.’ Finally, they chose to match the layout of the publication Face of Our Time, which allows the viewer to see each image as a ‘separate image first of all, and then as part of a pictorial continuum.’ Lange justifies this on the grounds that Sander’s photographs embody an ‘individual expressiveness’ as well as a ‘typological quality.’32 The Cologne edition also includes the annotations that Sander made on some of his portraits at the beginning of each volume, such as the note ‘Self-portrait marking the start of my project,’33 which Sander annotated alongside his self-portrait in Portfolio 42: Types and Figures of the City [Fig. 4].

These decisions to use Sander’s annotations and previous publications as a guide, justify their aim to recreate the project as authentically as possible, according to Sander’s vision. However, individual names are again restored to sitters and this goes against Sander’s intentions, and subsequently disturbs this claim to authenticity. Furthermore, giving the reader access to Sander’s notes means information is layered onto some individual photographs and thereby disrupts their seriality as equal parts to a larger whole. While these discrepancies exist, this edition is also aimed to further scholarship, allowing others who might not normally be able to visit the Sander archive, to conduct research on the project. Ultimately, in this publication and Gunther Sander’s, these additions alter the nature of the project, giving the reader access to information that Sander would likely not have used if he had completed the project himself, exposing what Derrida calls, a secret to its order,34 effectively changing the function of the archive from Sander’s vision. They are interpreting Sander’s work though and giving it a system under which it could operate legibly and legitimately.

Finally, in 2015, the New York Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) joined efforts to reconstruct the People of the Twentieth Century following their acquisition of a ‘complete’ set from the Sander family in 2015, printed from negative glass plates between 1990 and 1999. This is currently underway in the form of symposiums, inviting scholars to speak on a singular portfolio of their choice.35 These efforts to publish the archive are also accompanied by efforts to curate the archive, undertaken by institutions around the world.

As Derrida indicates in his text, and as the multiple reconstructions of Sander’s project by his family, The Stiftung Kultur, or the MoMA collection illustrate, there is a feverish desire for the archive. Furthermore, as Carolyn Steedman elucidates, this desire is not only in operating or using the archive, but also in owning it.36

Currently, Sander’s work is held in about twenty-four collections. As a result, it now has as many arkheions or residences where his work is interpreted and used by several different archons. The list is as follows:

37

37Each of these twenty-four collections house anywhere upwards of two photographs, (in the case of the Fotostiftung Schweiz in Switzerland)38 from People of the Twentieth Century. The largest collections can be found in four institutions across Europe and the United States: the Tate in London, The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles each own around 200 photographs, while MoMA now has the most with its recently acquired ‘complete’ set. Each collection is attracted to what could be termed a canonical group of Sander photographs that invariably includes images of Westerwald farmers or the Boxers, 1929 [Fig. 5]. And the attraction particularly of this last image is obvious: The Boxers have a theatrical presence, as the viewer consults the cheeky grin of the boxer on the right. It is not until the viewer looks down that they notice the shoelaces of the boxer on the left tied together and they can share in the joke. Yet, as a result, the original order of People of the Twentieth Century is often foregone for a collection of highlights which illustrates Sander’s career and artistic practice. It negates that People of the Twentieth Century was to be considered as a serial project, in which patterns and types take precedence, and which formed a distinct unit in Sander’s oeuvre. It is, at best, replaced with a new kind of seriality, one which conforms to a particular collection. So, for example, while the Harvard Museums has forty-nine photographs by Sander,39 and while these might build an understanding of Sander’s style, they cannot fully illustrate the intricate structure of the project. People of the Twentieth Century as a whole body of work is ontologically different across all institutions, meaning the way that viewers relate to these images is ‘determined by the form they assume in the various publications or exhibitions of his work, in which photographs… are ordered by editors, publishers, and curators.’40 Furthermore, the size of exhibition venues, as much as collection holdings or loan budgets usually condition such presentation of Sander’s project. Another example of how the archive is curated and how viewers relate differently to Sander’s archive is through the variation in titles of the photographs. Katherine Tubb highlights this variation in titles through the photograph of circus workers drinking tea.41 In the London Tate collection, the photograph is entitled Circus Workers, 1926-1932 [Fig. 6]. Yet, the MoMA collection calls it Indian Man and German Woman. These variations highlight how different collections interpret Sander’s photographs and change how the public relate to Sander’s images, emphasising the unrooted and unstable nature of People of the Twentieth Century as it stands today. Similarly, scholarship has frequently pointed out discrepancies contained within the overall project, honing in on the tendency of Sander’s types to move around, or to become what Miranda Wallace in her text “August Sander’s Photographic Archive: Fables of the Reconstruction” (2002), has termed ‘typologically mobile’.42 Austrian artist and writer, Raoul Hausmann, in “Raoul Hausmann as Dancer,” found in Portfolio 42: Types and Figures of the City, [Fig. 7] is one of the mobile figures. Firstly, because he is not a professional dancer, he is just modelling the role without being able to accurately fulfil that role outside of portfolio. Secondly, Hausmann also appears in various roles throughout the project. He is again featured as ‘Inventor and Dadaist’ in Portfolio 12: The Technician and Inventor, [Fig. 8] and once more standing between two women identified as Hedwig Mankiewitz and Vera Broïdo in parentheses, and entitled “The Dadaist Raoul Haussmann, 1929” in Portfolio 13: Woman and Man [Fig. 9]. This last portrait is extremely problematic for the order of types that Sander was constructing. It raises the question of whether Hausmann is cast in his role as a man or if his role is as he, Raoul Hausmann. As he is placed in a portfolio which looks specifically at these relationships between woman and man, the inclusion of Raoul Hausmann’s individual name in the title of the portrait upsets the transition to a type as it demonstrates his individuality rather than his gender. This problematises his place within the archive as an identifiable type, destabilising the technique of repetition which is supposed to stabilise the project.

Pointing out these discrepancies destroys the very fabric of the archive to construct order. It is not known if this was Sander’s intention. As Wallace points out:

There are some images which disturb the suggestion that Sander wanted to establish a firmly defined typological model of society. Whether we can put this down to conscious editorial work or simply to the work of the photographer himself is unclear.43

These collecting and research practices have left People of the Twentieth Century not only fragmented, but open to considerable variation and interpretation by multiple cultural environments who decide which of Sander’s photographs justify or authenticate a particular experience of his work as a whole. As a result, the original authority of People of the Twentieth Century is lost, as its organising principles of seriality which helped to stabilise Sander’s project no longer function in these environments. As Derrida puts it, ‘what is no longer archived in the same way is no longer lived in the same way.’44

Hannah Shaw, a reporter for the most recent August Sander Project Symposium held at MoMA at the beginning of this year, finishes her report with some questions, most notably:

… how do we get the most out of Sander? Should we approach People of the Twentieth Century as a living document, one that is most powerfully interpreted through our contemporary moment? Or do we gain more when we focus on reading Sander’s work through the history that cast him?45

The question of how to get the most out of Sander lies at the heart of this essay. People of the Twentieth Century has a long legacy of interpretation and reconstruction and it seems fit to end on an analysis of its most recent and ongoing attempt at MoMA. Reading The August Sander Project webpage, the first paragraph not only reads that it was never completed, but that it ‘has never been exhibited in North America.’46 Furthermore, to celebrate this milestone, MoMA believes that a set of symposiums over a five-year period will demonstrate a

thorough consideration of the breadth and depth of Sander’s project that will resist any certain geopolitical or art historical moment, an approach that nods toward Sander’s own careful, 62-year exploration of his subjects.47

The investigative model that MoMA uses is based on the fact that a complete iteration of Sander’s works has never been exhibited in north America before. Furthermore, their deployment of various scholars to talk about Sander’s work repeat the same processes as those who have already engaged with his work and they also reveal the same inconsistencies as those who have previously undertaken scholarship on People of the Twentieth Century. Derrida believes that deconstruction is something healthy for institutions to go through as it is a means for their legitimacy and for their survival. This practice that MoMA is undertaking of looking at Sander’s work appears unable to uncover something new or interesting or different in four years’ worth of symposia. Moreover, these symposia at best, distribute a carefully curated survey of arguments and observations that have already been made about the work. How is MoMA as an institution giving People of the Twentieth Century more space to diversify and transform as a work other than the fact that it has never been exhibited in North America before? MoMA may be producing more content for People of the Twentieth Century, but if this work is so significant for the cultural value of MoMA’s modern art collection, its method of engagement is problematic. Its practices are suggestive of compartmentalising the project, not allowing it to grow and evolve.

Sander’s work in People of the Twentieth Century is kept safe and alive in multiple collections and through multiple reconstructions. However, it has also been exposed to the collections different ordering principles and additions through its reconstructions which destabilise the project’s original ordering principles. The way that collections across the world and the reconstructions have treated People of the Twentieth Century engages in an archive fever or ‘burning with passion.’48 In the case of the collections, they engage in a fever by having the desire to hold some of Sander’s work. This fragments the organising fabric of People of the Twentieth Century, establishing a different project all together. In the case of the reconstructions carried out by Sander’s son, Keller, and Lange and Conrath-Scholl from the Stiftung Kultur, Cologne, they serve a purpose of recreating the project, of following its organising principles. However, they are more skeptical of these ordering principles and as a result, have added to the work, individuals’ names, breaking down the structural memory that Sander had consigned to each individual when he chose to arrange them as types. By adding biographical details to the sitters, they are augmenting the very fabric of the People of the Twentieth Century as established by Sander. Starting with the individual portraits, Sander’s son, Keller, and Lange and Conrath-Scholl effectively undermine the system from its point of origin. These practices, it can be argued, are a form of deconstruction or critique of the project. They also add meaning to People of the Twentieth Century by interpreting it. They are potentially improving it and replacing the original with another. Derrida elucidates this:

By incorporating the knowledge which is deployed in reference to it, the archive augments itself, engrosses itself, it gains in auctoritas [authority]. But in the same stroke it loses the absolute and meta-textual authority it might claim to have. One will never be able to objectivise it while leaving no remainder. The archivist produces more archive, and that is why the archive is never closed. It opens out of the future.49

The original People of the Twentieth Century may be rendered unstable by these choices, but it still means that its principles are being practiced and critiqued.

If we are going to uncover more about Sander’s work, if we want it to survive, we need to find a better way to engage with its fever, with its archival possibility. Sander’s work is not just incomplete, it is amorphous in nature. Are our institutions erasing that nature even, and especially in the process of producing it as a discernible work, as an archive of materiality? In other words, what do our institutions offer us when artwork enters into them? Are they giving artworks a space to breathe and be interpreted or are they closing them off, placing them in an archive to gather dust in the name of increasing a collections cultural value? That question is rendered ongoing from Derrida, Sander’s work, and the institutions themselves.

Figure details:

Please note, permission has not yet been granted to reproduce these figures so we have directed you to approximate reproductions online. We have noted when they have been catalogued differently.

Fig. 1: August Sander, Inmate of an asylum, 1926, Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur/August Sander Archiv, in August Sander and Gunther Sander, Men Without Masks: Faces of Germany 1910-1938 (Greenwich Connecticut, New York Graphic Society, 1973), 262. This figure is also viewable online at www.moma.org, catalogued under the alternative title Asylum Inmate.

Fig. 2: August Sander, Asylum Inmate, 1926-1930, Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur/August Sander Archiv, in Gabriele Conrath-Scholl and Susanne Lange, August Sander: People of the Twentieth Century, Volume 6: The City (Harry N. Abrams First Edition, 2002), 199. This figure is a cropped and more highly contrasted version of the above figure.

Fig. 3: August Sander, Bohemians, 1922-25, Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur/August Sander Archiv, in Gabriele Conrath-Scholl and Susanne Lange, August Sander: People of the Twentieth Century, Volume 6: The City (Harry N. Abrams First Edition, 2002), 185. This figure is also viewable online at www.moma.org, catalogued under the alternative title Bohemians [Willi Bongard and Gottfried Brockmann].

Fig. 4: August Sander, Photographer, 1925, Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur/August Sander Archiv, in Gabriele Conrath-Scholl and Susanne Lange, August Sander: People of the Twentieth Century, Volume 6: The City (Harry N. Abrams First Edition, 2002), 183. This figure is also viewable online at www.moma.org, catalogued under the alternative title Photographer [August Sander].

Fig. 5: August Sander, Boxers, 1929, Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur/August Sander Archiv in August Sander and Alfred Doeblin Antlitz der Zeit: sechzig Aufnahmen deutscher Menschen des 20. Jahrhunderts (Muenchen: Schirmer/Mosel, 1990), 43. This figure is also viewable online at www.moma.org.

Fig. 6: August Sander, Circus Workers/Indian Man and German Woman, 1926-1932, Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur/August Sander Archiv, in Gabriele Conrath-Scholl and Susanne Lange, August Sander: People of the Twentieth Century, Volume 3: The Woman (Harry N. Abrams First Edition, 2002), 71. This figure is also viewable online at www.moma.org, catalogued under the alternative title Indian Man and German Woman.

Fig. 7: August Sander, Raoul Hausmann as Dancer, 1929, Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur/August Sander Archiv, in Gabriele Conrath-Scholl and Susanne Lange, August Sander: People of the Twentieth Century, Volume 6: The City (Harry N. Abrams First Edition, 2002), 187. This figure is also viewable online at www.moma.org.

Fig. 8: August Sander, Inventor and Dadaist, 1929, Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur/August Sander Archiv, in Gabriele Conrath-Scholl and Susanne Lange, August Sander: People of the Twentieth Century, Volume 2: The Skilled Tradesman (Harry N. Abrams First Edition, 2002), 149. This figure is also viewable online at www.moma.org, catalogued under the alternative title Inventor and Dadaist [Raoul Hausmann].

Fig. 9: August Sander, The Dadaist Raoul Hausmann [with Hedwig Mankiewitz and Vera Broïdo], 1929, Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur/August Sander Archiv, in Gabriele Conrath-Scholl and Susanne Lange, August Sander: People of the Twentieth Century, Volume 3: The Woman (Harry N. Abrams First Edition, 2002), 49. This figure is also viewable online at www.moma.org.

Notes:

-

Gabriele Conrath-Scholl, “Notes – Perspectives on the Work of August Sander,” in August Sander: Seeing, Observing and Thinking Photographs, ed. Gabriele Conrath-Scholl (Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson, 2009), 14.

- Ibid.

- Oxford English Dictionary, “archive, The,” accessed June 13, 2019, https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/10416?rskey=YcSQFU&result=1#eid.

- Daniel Kieckhefer, “archive,” The Chicago School of Media Theory, 2007, https://lucian.uchicago.edu/blogs/mediatheory/keywords/archive/.

- Carolyn Steedman, “Something She Called a Fever: Michelet, Derrida, and Dust (Or, in the Archives with Michelet and Derrida),” in Archives, Documentation, and Institutions of Social Memory, (University of Michigan Press, 2006), 4.

- Derrida and Prenowitz, “Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression,” 9.

- Steedman, “Something She Called a Fever: Michelet, Derrida, and Dust (Or, in the Archives with Michelet and Derrida), 4.

- Derrida and Prenowitz, “Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression,” 59.

- Ibid., 57.

- Derrida and Prenowitz, “Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression,” 57.

- August Sander, “Photography as a Universal Language” (1931), in August Sander: Seeing, Observing and Thinking, ed. Gabriele Conrath-Scholl (Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson, 2009), 28, Sander confirms this number of photographs in this radio lecture: “Menschen des 20. Jahrhunderts [People of the Twentieth Century] comprises around five or six hundred photographs…”

- Derrida and Prenowitz, “Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression,” 38.

- In regards to the usage of the word “exclusion” I mean anything that is not a portrait would be excluded from the project. For example, Sander is less likely to use landscapes for his project. Although, he does decide to include two in Portfolio 36: Streets and Street Life at the beginning of the portfolio. They depict firstly, a Cologne street in action, and the train line which runs through the heart of the city.

- Gretchen Wagner, “Vom Gesicht zum Gesicht,” in Athanor XXI, ed. Allys Palladino-Craig (2003), 57.

- August Sander, “Photography as a Universal Language” 1931, in August Sander: Seeing, Observing and Thinking, ed. Gabriele Conrath-Scholl (Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson, 2009), 30.

- Gabriele Betancourt-Nuñez, “Positions within the Photographic Dialogue,” in Portraits in Series: A Century of Photographs. Eds. Gabriele Betancourt-Nuñez and Ulrike Schneider. (Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, 2011), 15.

- George Baker, “Photography between Narrativity and Stasis: August Sander, Degeneration, and the Decay of the Portrait,” October, Vol. 76 (1996), 82.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Rosalind Krauss, “Photography’s Discursive Spaces: Landscape/View,” Art Journal, Vol. 42, No. 4, The Crisis in Discipline, (1982), 316.

- Gunther Sander, “Photographer Extraordinary,” in Men Without Masks: Faces of Germany 1910-1938, ed. Golo Mann and Gunther Sander (Greenwich, Connecticut: New York Graphic Society Ltd., 1973), 314.

- Miranda J. Wallace, “August Sander’s Photographic Archive: Fables of the Reconstruction,” Visual Resources, 18:2, (2002), 155.

- Derrida and Prenowitz, “Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression,” 10.

- Wallace, “August Sander’s Photographic Archive: Fables of the Reconstruction,” 157.

- Sander, “Photographer Extraordinary,” in Men Without Masks, 299.

- Carolyn Steedman, “Something She Called a Fever: Michelet, Derrida, and Dust (Or, in the Archives with Michelet and Derrida),” 4.

- Linda Keller, Ulrich Keller, and Gunther Sander, August Sander: Citizens of the Twentieth Century: Portrait Photographs (Cambridge MIT Press, 1986), 3.

- Die Photographische Sammlung, “August Sander (1876 -1964), accessed 30/05/2019, https://www.photographie-sk-kultur.de/en/august-sander/august-sander/

- Ibid.

- Hili Perlson, “Cologne Foundation Challenges Hauser & Wirth Over August Sander Estate,” artnet, February 17, 2017, accessed June 20, 2019, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/cologne-foundation-challenges-hauser-wirth-august-sander-864383.

- Gabriele Conrath-Scholl and Susanne Lange, August Sander: People of the Twentieth Century (Harry N. Abrams First Edition, 2002), 15.

- Susanne Lange, “Editorial preface to the new edition of August Sander’s work People of the 20th Century,” in August Sander: People of the 20th Century (Volume I) (Harry N. Abrams First Edition, 2002), 13.

- Gabriele Conrath-Scholl and Susanne Lange, August Sander: People of the 20th Century (Volume 6), 20.

- Derrida and Prenowitz, “Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression,” 11.

- Another symposium was held at the beginning of this year, January 24, 2020.

- Steedman, “Something She Called a Fever,” 4.

- “Über die August Sander Stiftung,” August Sander Stiftung, accessed June 20, 2019, https://augustsander.org/

- “Fotostiftung Schweiz, Sammlung Online,” Fotostiftung Schweiz, accessed June 20, 2019, https://fss.e-pics.ethz.ch/#1561161910218_4.

- “August Sander,” Harvard Art Museums, accessed June 20, 2019, https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/collections?q=august+sander.

- Wallace, “August Sander’s Photographic Archive: Fables of the Reconstruction,” 156.

- Katherine Tubb, “Face to Face? An Ethical Encounter with Germany’s Dark Strangers in August Sander’s People of the Twentieth Century,” Tate Papers, No. 19, (Spring, 2013), accessed January 16, 2019, https://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/19/face-to-face-an-ethical-encounter-with-germany-dark-strangers-in-august-sanders-people-of-the-twentieth-century.

- Wallace, “August Sander’s Photographic Archive: Fables of the Reconstruction”, 163.

- Wallace, ‘Fables of the Reconstruction,” 162.

- Derrida and Prenowitz, “Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression,” 18.

- Hannah Shaw, “The August Sander Project, Year Four: People of the Twentieth Century as Gesamtkunstwerk,” Assets, MoMA, January, 24, 2020, accessed May 20, 2020, https://assets.moma.org/d/pdfs/W1siZiIsIjIwMjAvMDEvMjQvNnRremV2dndyZ18yMDE5X0F1Z3VzdF9TYW5kZXJzX0Nocm9uaWNsZV9GSU5BTC5wZGYiXV0/2019_August_Sanders_Chronicle_FINAL.pdf?sha=1aae23bf53edde72

- “The August Sander Project,” MoMA, 2020, https://www.moma.org/calendar/programs/113.

- Tyler Green, “The August Sander Project: Beginning a Five-Year Exploration of Sander’s People of the Twentieth Century,” MoMA August Sander Project Blog, November 16, 2017, https://assets.moma.org/d/pdfs/W1siZiIsIjIwMTkvMDEvMjgvNjk4eTlodHhicV9BdWd1c3RfU2FuZGVyX0Vzc2F5MV9WMS5wZGYiXV0/August%20Sander%20Essay1_V1.pdf?sha=b9deffc99a80df7d

- Ibid., 57.

- Derrida and Prenowitz, “Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression,” 45.

Elizabeth Smith is a recent University of Western Australia graduate, receiving Honours in Art History in 2019. Over the past twelve months she has been developing her practice, including working with newly-formed, Perth-based artist-run-initiative, Pig Melon; has been part of Room01 Collective, an arts organisation which explores nascent arts practice in Western Australia; co-curated, with Aimee Dodds, the second iteration of Artsource’s (e)merging project; and, worked with The Lobby to develope an exhibition taking place in November 2020 as part of its emerging curatorial program. Liz hopes to continue to explore different opportunities within the arts as an independent curator and writer.

Currents is a collaboration between the Centre of Visual Art (CoVA) at the University of Melbourne and the School of Design, University of Western Australia, and is funded through the Schenberg International Arts Collaboration Program. The Advisory Board and Editorial Committee are comprised of staff and graduate students from across the University of Melbourne and the University of Western Australia.

Currents acknowledges the traditional owners and ongoing custodians of the land on which this journal is produced—the Boonwurung and Wurundjeri people of the Eastern Kulin Nation and Whadjuk people. We pay our respects to land, ancestors and Elders, and know that education involves working with their guidance to improve the lives of all.

ISSN 2652-8207

![]()

![]()

Currents acknowledges the traditional owners and ongoing custodians of the land on which this journal is produced—the Boonwurung and Wurundjeri people of the Eastern Kulin Nation and Whadjuk people. We pay our respects to land, ancestors and Elders, and know that education involves working with their guidance to improve the lives of all.

ISSN 2652-8207