The link, the limits between: performance and capture in the moving image

Jen Valender in conversation with Gabriella Hirst

To cite this contribution:

Valender, Jen. Interview with Gabriella Hirst. ‘The link, the limits between: performance and capture in the moving image’ . Currents Journal Issue Two (2021), https://currentsjournal.net/The-link-the-limits-between-performance-and-capture-in-the-moving-image

Download this interview ︎︎︎PDF

Jen Valender’s course of study:

Master of Fine Arts, Faculty of Fine Arts and Music, Univeristy of Melbourne

Image ^^^ Gabriella Hirst, Darling Darling (2021), two channel moving image installation 24:55, Commissioned by the Ian Potter Cultural Trust for the Ian Potter/ACMI Moving Image Commission 2020. Photograph: Felicity Jenkins, AGNSW.

April

9, 2021, a little after 10am. The sun, intense. The blinds, drawn. Noir-esque

strips of light fall across the screen as Zoom connects our call.

Gabriella Hirst — (moving about) I’m still kind of resetting myself up here. I’m staying in Sydney for… I don’t know. For an indeterminate amount of time. I’m subletting a room from a friend at the moment, so I’m kind of awkwardly, moving around their place trying to kind of settle in different corners. In between places.

Jen Valender — (from Melbourne) Of in between places… you live between London and Berlin. What brought you back to Australia? Why now?

I moved over to Berlin eight years ago, then moved to London to study, then back to Berlin where my partner lives because of Coronavirus, as it was a safer place to be. Well, it was in March [2020]… then I came back here for a couple of exhibitions: the ACMI Ian Potter, Moving Image Commission and The National. They were planned and then delayed and delayed and delayed. That was one reason, but of course as the year went on, not being able to get back and see family was affecting my whole life over there. So many people obviously feel this at the moment, but it changes everything, to not be able to get home. I was in Berlin for most of 2020.

You were creating the work for ACMI at that time?

I actually got the commission early 2019 and it was going to launch at the beginning of 2020. It got pushed back. I had made the majority of the film, I had the edit, I hadn’t done the sound or the grade by that time, which I was going to finish in the UK. It all became kind of impossible… Until it became possible!

Congratulations. How are you feeling now that it’s open to the public?

It feels good. I still feel I’m letting go of it. It’s been such a protracted process. I started this work, really, in 2018. I had the idea for it and came back to Australia, made a draft, had interviews and everything. But the quality was relatively poor, and it didn’t hold the [concept of the] work. Then, when I had the commission, I was able to do it in a way that suited the content. It really made the work what it is; what it couldn’t have been if it had been my usual way of making [with a zoom recorder and a little camera]. So, it was a really long process. After it opened at ACMI it didn’t feel real because the city went into lockdown the day after it opened. Other programs were cancelled around that. I was incredibly lucky and privileged to be able to open the same work again a month later as part of The National 2021 at AGNSW. I changed a few details also between that time to suit it to that particular space. It felt more complete then.

When I visited Darling Darling at ACMI, it was as if there were two stages and two bodies of performance happening. On one side, you’ve got the Barka Darling River landscape, and the AGNSW painting conservators performing on the other. Can you talk about the experience of those two sites?

I’ve been working on this project for so long… I haven’t had the space yet to be able to talk theoretically about my own performative relationship to that work. I feel when it’s a work, in which it’s only me and my camera, I can do that really fluidly. I’m still trying to form what that is for Darling Darling, because it was such a shift in my way of working. It involves so many people, it was a very resourced work. There are so many moving parts to a work when it gets scaled up, it’s quite difficult to locate myself within the performance. I see the work more as a gaze being implanted, to form how that place is perceived or represented, which I would understand as my own performance. So, I would bring that back to me, rather than how the land is performing. Because the land is understood completely differently depending on who’s looking at it and who’s experiencing it. One of the things that I’m still unpacking and trying to untangle is what it means for a non-Indigenous Australian person to go out on country and to capture [film].[1] The work is about a particular type of capture [in paintings] from the late 1800s, and how that form of capture lingers on. The lens continues that form of capture. I am the capturer and question where I positioned myself within that process. I don’t think there’s a clean answer to that.

It makes me think of when we’re working with others—be that land, people, animals or something else—it’s often wrapped up with ethics.

Absolutely.

Image ^^^ Gabriella Hirst, Darling Darling (2021), two channel moving image installation 24:55, Commissioned by the Ian Potter Cultural Trust for the Ian Potter/ACMI Moving Image Commission 2020. Stills courtesy of Gabriella Hirst.

As a non-Indigenous Australian person performing or capturing in different ways on the landscape, what were the ethical considerations you had to wade through before you began this project?

I did a lot of research. I did several site visits, I started working very closely with the amazing artist and activist, Elder Uncle Badger Bates—who advised me on specific areas that I should not film, for cultural reasons, and others that I should focus upon in order to have people witness the destruction taking place there. Uncle Bates explained to me what I was capturing in ways that provide a bit of shaking up to the sense of entitlement that I think is a big part of a Western artmaking ideology—to be able to go anywhere and capture anything. In terms of navigating the ethics of that, I did try to complicate what the boundaries of that tradition of capture are. By the same token, I position myself very much as a visitor and in a role of trying to sit in that uncomfortable space. To think about what that uncomfortable space is. I don’t know if that’s the first and foremost thing that people will get from the work, because there are different layers. Perhaps the primary thing is the care/lack of care absurdity that’s played out. I’m also preoccupied with where I sit within that and what does it mean for me to re-perform acts of capture. In terms of the ethics, I don’t know if one can re-perform something and for it be ethical. I have been doing this in my practice in different ways and I wonder whether it’s the right thing to be doing. I feel by complicating these archival categories of capture, or of power, by re-performing them in ways that maybe show some of the violence embedded within them, particularly in something that might be considered to be very benign—I think that’s worthwhile. That’s something that I can approach and feel comfortable approaching; it’s my place to try and unpack that. Whether that be through romantic landscape painting or, in other projects, looking at things that I find beautiful and serene. I try to dig underneath and ask: why? Rose gardening has been another project that I’m working on. I really dig into things in very concrete ways. In this other project, How to Make a Bomb, there’s an 8000-word essay that I’ve written to accompany the work. On the other hand, I have works that are a lot vaguer, they’re not situated within a particular body of research. They’re more situated within this interest in capture and control.

Recently, I started reading Ariella Aïsha Azoulay and she talks a lot about a kind of entitlement, within the idea of what art is—to go places and to take—and how that follows through in the camera. The impulse of creative-taking is something that I always grew up with—the artistic ‘license’—that you can make whatever you make and capture whatever you want. That’s something which feels at the core of a romanticised idea about making. That’s a really interesting place to straddle. Maybe the actual act of creative expression in its own right, is really ethically flawed if it’s fundamentally based on an entitlement to take—it’s a concrete colonial impulse. There’s a lot to unpack there. On the other hand, how do you then contradict that and continue making?

It’s an interesting, messy and fecund area where you could really get lost and tangled up.

Maybe that’s okay—to get lost.

I feel that problematising is what’s happening behind the screen in art most of the time.

Mmmmmm.

In terms of when you were speaking about performing—when in the past it would be yourself performing in the work. In those instances, do you feel it’s performance that’s being—to use your term—‘captured’ by film? Or is it visual material that is being created for the film? It’s the ultimate question: is it film or performance that is being documented?

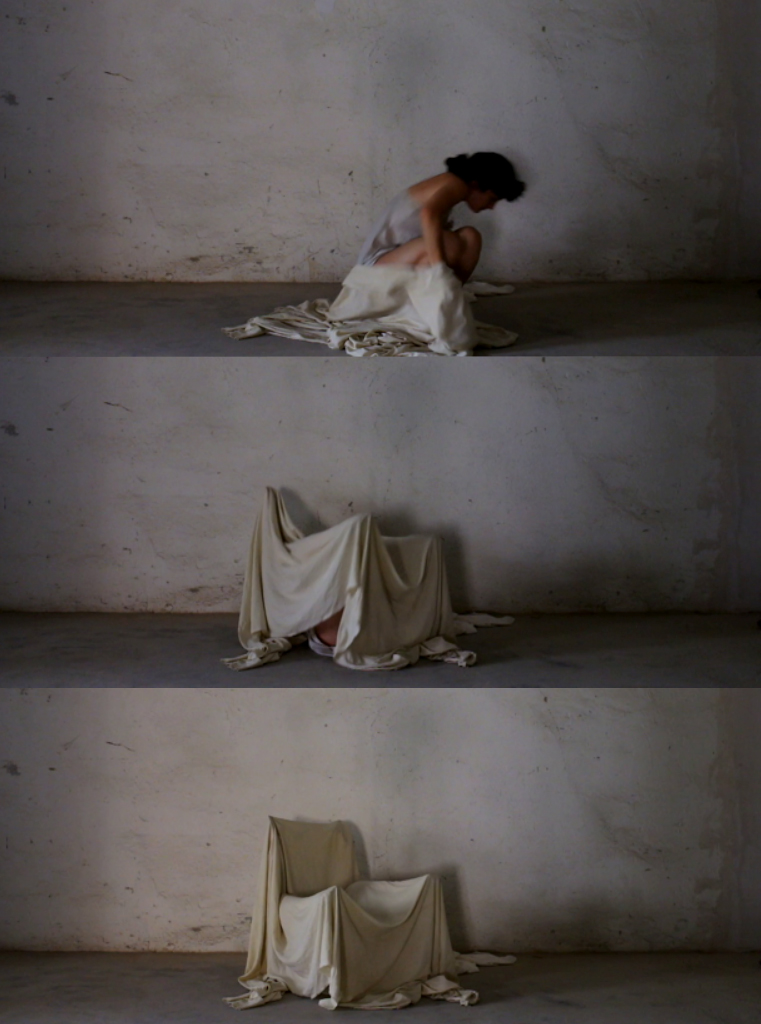

I think it’s a blurring of those two. It’s both. I think the slippage between those two is what’s really fascinating. I’ve had this conversation with a couple of painters. A friend, Ellie McGarry, was explaining her process to me, and how she feels as if she’s always in rehearsal. She’s painting, constantly in rehearsal, then, eventually, she does a performance. She doesn’t know where it is, where the link, the limits between the performance and capture are, it’s very hazy. But when it comes to a work like Interlude, that was very much a study to do something else. It kind of crystallised a lot of things, where it was just me with my little camera—it’s still my favourite camera, even though it really doesn’t get much bitrate. But I still go back to it, because it’s immediate. The work [Interlude] is a very short, almost 70s-ish performance, where I go underneath a sheet and become slowly hidden; shrouded, as if becoming this chair/object, and then holding that for as long as possible. The work slips between being an object and a person, between a performance and a still [image]. That’s something that I really was exploring, and I’m still exploring, to some extent, through Darling Darling. But I haven’t been able to unpack that yet. I’ve often come up with works, imagining them as a performance and then documenting them and then finding that there’s actually a very strong relationship with the camera there. It’s not that I look at it and then I decide, ‘Oh, this works better as a video’. I was already making it for video. It’s an interesting question, because I accidentally started working with film.

Some of your works aren’t specifically moving image in their outcome, yet still have some kind of performative element. How to Make a Bomb, for instance, sees the roses performing in situ, growing in the gallery. Did the performative element come from making films? Or was performance something that’s always been there, in the background, in some way?

Until I went back to university to do an MFA, I didn’t consider what I was doing as performance for some reason. The filming came later, definitely the filming was a means to perform. When I did my undergrad, I remember making kinetic sculptures and wanting them to exist within a space and then making a film. I studied painting and photography and was making images through a camera lens: composing. That slowly became more than a means of recording.

I’ve been making performance for years without calling it performance, and not knowing exactly what I was searching for in that—I think it’s something to do with a liveness. Particularly when I started making work that had long protracted research behind it. Trying to hold on to a liveliness and the excitement in making, and also perhaps romanticising the artistic process by thinking that it needed to always be very alive, and not realising exactly what that means. I think I stopped painting because I started to find it deeply boring. The thing that I was missing in that was the performative element, which I know that people who really work on it, find it within it [painting]—they get there. But I was finding it really boring. I started moving to other mediums that felt more live, and perhaps in hindsight, that’s what I was looking for—that kind of space, where you’re performing, when you’re making and less present. You’re not thinking as much when you are making. I find that quite hard to do. I am constantly trying to analyse what I’m making. But I want both. I want to be able to have performance making, not consideration, yet I also want to be considerate in what I’m doing—I want a balance between the two. Because I think total abandonment within a creative process proves unethical. The more I research into these fields of total abandon within a Western cultural expression, these romantic paintings, the more I realised that they’re wrapped up in the perpetuation of violence. I remember going out to Hill End as a painting student, which is a painting colony that still somehow exists in New South Wales. It was a beautiful place, but I remember there being this thing about painters there going off into the bush and it was very romantic. You know, the whole place is beautiful, everyone’s cooking really lovely food and there are lovely artist residencies there—but the focus of the place is very much on post 1788, settler colonialist and gold rush histories, without the focus on the Indigenous Australian relationship to country in that place. There’s something dangerous in a pure ‘falling’ into making without being considerate and without doing research. So, I don’t know. I feel that. I want that. But I also want to be able to think deeply and make at the same time. I’ve been looking for that through moments of performance in a way. I don’t know if that’s one thing. But that’s one answer.

Images ^^^ Gabriella Hirst, Interlude (2017), Single channel video, 6:50. Stills courtesy of Gabriella Hirst and How To Make A Bomb (2018-2021), Supported by The Old Waterworks and Arts Council England. Photograph: Andrei Vasilenko at CAC Vilnius.

Do you feel you’re performing as yourself in the works? Or is there some kind of method or character, or is it something else?

No, it’s me… it depends on which work. In Force Majeure, which was this painting in a storm work that I made in 2015, the research behind that was looking into a bunch of different historical figures, including Iso Rae, a white female painter from Australia, who had gone to Europe in the late 1800s and moved to an artist colony in France. Everyone else had gone home when World War One broke out, except her and her sister in this seaside village where they were painting, which became an army barracks. They stayed on and kept painting sunsets and I found that really interesting, the bizarreness of that. I was researching and thinking about her. Also at that point, I had been given a scholarship to go over and live in Europe, so I was thinking about what it means to send someone, somewhere—to send someone from Australia to Europe to make art.

I

was also looking at, Ivan Aivazovsky, a Russian court painter who was famous

for painting storms—huge canvases of storms at sea. He would do that from the

comfort of the court in St. Petersburg. Again, it’s this idea of how close you

can be to something destructive and still make. I was thinking about those

people when I was performing in that particular work. I also had a friend of

mine come with me to this particular place to film and I had a cinematographer

who came with me. We kept waiting. We had very little budget and we’re in a

seaside town in northern Germany, on the Island Rugen, where Caspar David

Friedrich would go to paint. We were there for over a week, and then another

week trying to find a storm. Eventually, they had to go back to their lives. So,

they left. To film, I had a camera that I had strapped to a tree. No one else was

there. That’s when it happened. That’s the take. First of all, that was when

the weather happened to come. But I think there’s also something about not

having people’s gaze on you and the intimacy of the camera’s gaze and being

able to forget about the camera’s gaze when you’re in a situation—where it’s you

and the camera, you can get to a point perhaps where you can forget that the

camera is there, and you can be performing. That’s what happened in that

work. That’s why I stuck with that take.

When I see that work, it doesn’t feel like something that you were waiting for. It feels spontaneous.

It’s that moment. Almost when you can forget that it’s a performance.

And you’re living it…

Definitely.

![]()

![]()

Image ^^^ Gabriella Hirst, Force Majeure (2016), Single channel video 14:50, Commissioned by the Australian Centre of Contemporary Art, Photograph: Andrew Curtis.

When you perform in your own work, does that ever come across as a sort of self-consciousness or an indulgence?

It really depends on the work and who you are within the work. I’ve started to develop a belated allergy to works which treat oneself as Human A within a work. That’s something that I feel I’m quite sceptical of now. Even if the work is personal, it ends up lacking in the critique of what it means to use yourself as Person A—as the neutral—as if your body is neutral, which it isn’t. That’s something that I’m working on, in terms of being self-conscious and would be concerned of.

The most recent thing I’ve made, which isn’t even a work, it’s a performative thing that keeps the practice going—which I hadn’t done since the pandemic started, because I didn’t have the energy…. There are these plants that are from my grandparents place that I became fascinated with because they only bloom overnight and then they die. They are night-blooming cereus. I’d heard, when I was a child, that you’d have to wait up to see them. When I was living in the UK, my grandparent’s house was being sold. For some reason, I really fixated on these plants and started writing about them. I went back when I returned to Australia and for the first time, I use 16mm and I filmed the house, and I filmed that plant. I felt using 16 mil was a way that I could really blur filming and performance because there’s a scarcity embedded within it. For me, at least that first time using such light sensitive, expensive materials, there was a precarity that I rarely consider as a maker. I think 16 mil is a way that I could work in terms of performative filmmaking.

That plant itself bloomed when I was back here. I went out with my digital camera and my phone and my phone’s light and was filming it—I felt I had to film it, because it’s this plant that I’ve been waiting to see for so long, and I needed to bear witness to it, and filming it would solidify that. I, whilst I was filming, became aware of the violence of filming it. That it was, perhaps, the violence of trying to record something instead of witnessing… it kind of became this strange performative activity where I was filming it whilst destroying it, or something like that. It’s this footage that I have, and I, I’m really excited by it. I don’t know what it is, but I need to go back to it. I don’t feel any self-consciousness in doing that, because it’s such a personal story. It might not actually connect to anyone, because it’s very personal and abstract. Hopefully, it would. Hopefully, there’s something within the kind of material itself, that will translate to something underneath about the violence of witnessing, that other people might be able to connect to. But I don’t feel any self-consciousness. If I was using my whole body (only my hands are filmed), it would feel different.

Can you talk a bit more about this term ‘Person A’; what does that mean to you in your practice?

Recognising that everyone’s body is politically loaded and if you are recording a body, and showing it, you’re not neutral. To treat yourself as a body as neutral is a problem. There’s a long history of white people, in particular, treating themselves as the subject, whilst anyone who doesn’t conform to that is the ‘other’. That’s what I mean by Person A. That doesn’t mean I wouldn’t use my own body, and I definitely will use my body again, but it’s trying to have an awareness of that. The location of my body—which could also have been my body behind the camera, as well. It’s particularly poignant when it comes to representing your own body, I think. What do you think?

It’s incredibly hard to be the subject and analyser at the same time, but I think it’s also incredibly necessary. I’m curious about how to grapple with that problem myself.

I think it’s something that we grapple with and we try it out. There’s no set answer. Also, I feel I’ll probably make works and not always show them. I have a whole library full of performance films. They are little private performances and maybe they will become an archive of shorts at some point. But they’re more the performances that keep the practice going.

There’s an interesting relationship between filming and conservation. Filming, in a way, conserves a moment in time or a performance.

Absolutely. It’s a witnessing and, therefore, a recording of a witnessing. I use the word witnessing not to mean to live and experience, but to be a witness to something and to testify for its existence. Also, to consider that the camera is a witness and asking what makes the cut? What is burned in?

It could be argued that your practice is driven by concepts or forces that are clashing or rubbing up against each other in some way. Can you talk about that formula and what might be driving it? This method of pairing?

That’s something that has become more apparent in recent years from an interest in finding structural links between things. I do big mind maps, big drawings, where I know there’s some connection. For instance, the atom bomb rose project was about finding that material and knowing that there’s something in that I can’t quite figure out. There’s something violent within that plant that I don’t feel displaying that material as it is explains that. It’s about teasing out the hidden violences between/within things, or the hidden contradictions, when something seemingly benign is not necessarily what it seems. I think that’s something I’m kind of intrigued by at the moment. I have other ideas for projects that operate on a similar principle. Eventually, I’ll probably move in a different direction. Though I do think there’s something about placing two different, perhaps unexpected, materials together that has the opportunity to produce new knowledge in a nuanced way. Like basic montage theory—by placing two images together your mind makes its own narrative of what joins them. It creates a grey space where you can make your own conclusions between them.

Going back to Darling Darling, when an artwork has an environmental theme or an environmental critique or claim it often enters an interesting space of contradiction, in that the work comes with a level of waste or consumption associated with its production. Did that critique or problem come up for you and your work? And if so, how did you reason with it?

It’s very difficult to reason with. I flew to make this work. I flew twice – that’s contradictory and it’s anti-ethical. But I don’t feel that discounts, necessarily what the work is saying, because the work is not purely an environmental cry for conservation or care. It’s more of a scrutiny. It’s a way of scrutinising structures of care, structures of value, structures of hierarchy. It’s interesting, I was speaking with Charles Lawler, who is a technician at AGNSW about the work. He said he sat down and watched the work properly for the first time. The main thing that came out of it for him was how absurd the whole thing is. I really like his take on it, because we all end up being little cogs in this big machine of making and doing our little thing and carrying on with our little project. Much like the conservation side [of that work], we’re all doing our little tasks, doing our jobs—the absurdity of that, considering the destruction of the habitat that we need to survive in, the absurdity of us continuing on with our jobs, and how it can seem as if there’s very little way out. That’s not a cop out. I think it’s very difficult not to. I tried to be upfront with that in the work, in my own coded way. There’s a little SD card in the work which has been gold leafed. That was a way of wrapping myself up within the process and this art history—that I’m not separate from the art history that I’m critiquing. I’m not separate at all from the machine of art making that continues to be complicit in habitat destruction and world destruction and ideologies of damage. In this work, I’m trying to look at the structural issues underneath. Going forward, I will not be flying across the world to make work. But I guess for this work, to follow it through and to make it required some of that contradictory making. It’s a difficult question, though, because I feel conflicted about it.

It’s very human to have that sort of conflicted friction in the work.

I think it was also a surprise to me how resource heavy it is to make a work like that. The travel costs, the batteries for the camera, bringing a cinematographer out into far regional New South Wales, etc... all of these things that ended up being very resource heavy. I’m used to operating quite lightly, but still, you know, between different countries. It was a surprise to realise what it can take to make that sort of work. I was sceptical of that, whilst I was making I had doubts whether I was going about it in the right way. But I think we always have doubts when we’re making something in a way for the first time, and I’m really glad I followed through with it. I had a lot of amazing people to guide me, a wonderful team of collaborators and supporters, and friends who I asked for advice. Because I don’t think the work could actually express its message, if it was me and my camera. It would be a very different work. Maybe that’s okay, maybe I will make a very different work next time. It’s interesting—big, shiny moving image works come with a certain way of working. You can obviously break the mould and make them in your own way, but I feel that sometimes you’ve got to know the mould before you try and break it.

I’ll end on a lighter question. Are there any references in your career or artists that you keep coming back to when you’re making works? And from those influences (dead or alive), who would you invite to your next opening?

I feel they’ve changed a lot in recent years... Who would be yours?

I like the idea of Žižek turning up, perhaps getting drunk and spitting through his lisp at people, creating a bit of a scene in the gallery.

There’s an Italian director, who I really love at the moment, Alice Rohrwacher, who made the film Lazzaro Felice [Happy as Lazzaro]. I’ve been obsessed with that film for a while. It’s a surreal, magical realist, beautiful film. Her work is incredible.

My answer used to be someone like, Ragnar Kjartansson, because I really love his work. But I also don’t feel like I would really want that feedback... I think also, some really amazing artist friends—an artist called Andrea Canapa, who I met when I first went overseas. She lives in Berlin and is from Peru. We call one another and talk. Or Laura Hindmarsh… I think there’s about five artists, friends who I’ve had, who I call up regularly, and we talk through our issues, ideas, we work through what we’re working on, and ask: is this too provocative or not provocative enough? We care about one another’s practices and we’re not competitive. We care about one another. I actually feel, I know, this is a cheesy thing to say, but they’re the only people that I would want there.

It’s a rare, beautiful thing to have a community like that, where you are not competing.

Three of them are from German scenes, then there are people that I studied with. My Master’s course was called ‘Media Studies’, but a lot of it was performance. A lot of people hadn’t performed before and we were really vulnerable. Many of us did really uncertain performances as part of it. But when you do uncertain performances, you’re vulnerable in front of people. I remember doing a performance once in a shower. I wasn’t sure about it and I was really nervous. I did it twice in a shower at a public opening. The first time around, I thought, ‘oh, that really sucked’. Then the second time around, I looked up and three of my really close friends had come and it was this miserable night in the far end of deep South London. It made it. I think it’s those people that make it.

I have a friend who introduced me to making performance and she’s a performance artist with a capital P. A. She introduces herself as a performance artist. She’s from Estonia and studied Estonian performance art. She’s researched heavily into what performance art in that part of the world has meant politically and is the first person that I did a performance with, that would be considered as a performance. I asked, ‘can we do it when there’s not anyone around?’ I felt too vulnerable. So, we filmed it and that was a thrilling experience. I think that was a really pivotal moment—when someone said, ‘you can do this’. Then when I went to study in London, someone was putting on a performance art night within our cohort at a pub nearby. I did a performance of singing and I’d always been really scared to sing in public. But it felt like the right community, I could do that and be vulnerable, but also be okay. Another artist friend was there and she ended up doing a performance where she wore her pyjamas and rolled across the floor. Ever since then she has said, ‘oh, it was terrible’, but it wasn’t. It was a really great thing to put yourself in, we did things that made us really scared. The singing was terrible. I ended up going there and re-performing it later as a film, which has been the thing that’s been shown since then. But the actual performance at the spot was so vulnerable that I didn’t know what to think about it. I almost needed to make a film about it so that I could think about it. It’s those moments where you feel you have the support to actually make yourself vulnerable in that way and make the performance that you’re doing privately all the time in your practice and make it public to really push you.

If you are pushing all the time, if you’re nervous and you’re taking a risk, you might be doing something right. Something worth doing.

Exactly.

About the interviewee:

Gabriella Hirst (she/her) was born and grew up on Cammeraygal land and is currently living between Berlin and London. She works primarily with moving image, performance, and with the garden as a site of critique and care. Gabriella’s practice and research explores connections between various manifestations of capture and control - spanning plant taxonomies, landscape painting, art conservation and nuclear history. Gabriella recently launched Darling Darling, the 2020 ACMI/Ian Potter Moving Image Commission, which is currently showing at ACMI and AGNSW. Her upcoming projects include An English Garden at Estuary 2021, Essex, and ‘Tip of the Iceberg’ at Focal Point Gallery, UK. Gabriella is currently an associate lecturer in Media Studies with the Royal College of Art, School of Architecture in London.

About the interviewer:

Jen Valender is an Australasian artist and writer from Aotearoa based in Narrm Melbourne whose practice-led research explores the relationship between moving image, sound and psyche. She uses cinematic devices, performance lectures and reflexive writing methods to sculpt undercurrents of relational ethics and poetic problematics that are surfacing in her practice. Jen is a recipient of the Next Wave Precinct Art Prize and the Ian Potter Museum Miegunyah Research Project Award. She holds a BA (Sociology) from Victoria University of Wellington, NZ and a BFA (Hons) from Monash University and the Victorian College of the Arts. Jen is currently an MFA (visual arts) research candidate at the VCA, University of Melbourne.

When I see that work, it doesn’t feel like something that you were waiting for. It feels spontaneous.

It’s that moment. Almost when you can forget that it’s a performance.

And you’re living it…

Definitely.

Image ^^^ Gabriella Hirst, Force Majeure (2016), Single channel video 14:50, Commissioned by the Australian Centre of Contemporary Art, Photograph: Andrew Curtis.

When you perform in your own work, does that ever come across as a sort of self-consciousness or an indulgence?

It really depends on the work and who you are within the work. I’ve started to develop a belated allergy to works which treat oneself as Human A within a work. That’s something that I feel I’m quite sceptical of now. Even if the work is personal, it ends up lacking in the critique of what it means to use yourself as Person A—as the neutral—as if your body is neutral, which it isn’t. That’s something that I’m working on, in terms of being self-conscious and would be concerned of.

The most recent thing I’ve made, which isn’t even a work, it’s a performative thing that keeps the practice going—which I hadn’t done since the pandemic started, because I didn’t have the energy…. There are these plants that are from my grandparents place that I became fascinated with because they only bloom overnight and then they die. They are night-blooming cereus. I’d heard, when I was a child, that you’d have to wait up to see them. When I was living in the UK, my grandparent’s house was being sold. For some reason, I really fixated on these plants and started writing about them. I went back when I returned to Australia and for the first time, I use 16mm and I filmed the house, and I filmed that plant. I felt using 16 mil was a way that I could really blur filming and performance because there’s a scarcity embedded within it. For me, at least that first time using such light sensitive, expensive materials, there was a precarity that I rarely consider as a maker. I think 16 mil is a way that I could work in terms of performative filmmaking.

That plant itself bloomed when I was back here. I went out with my digital camera and my phone and my phone’s light and was filming it—I felt I had to film it, because it’s this plant that I’ve been waiting to see for so long, and I needed to bear witness to it, and filming it would solidify that. I, whilst I was filming, became aware of the violence of filming it. That it was, perhaps, the violence of trying to record something instead of witnessing… it kind of became this strange performative activity where I was filming it whilst destroying it, or something like that. It’s this footage that I have, and I, I’m really excited by it. I don’t know what it is, but I need to go back to it. I don’t feel any self-consciousness in doing that, because it’s such a personal story. It might not actually connect to anyone, because it’s very personal and abstract. Hopefully, it would. Hopefully, there’s something within the kind of material itself, that will translate to something underneath about the violence of witnessing, that other people might be able to connect to. But I don’t feel any self-consciousness. If I was using my whole body (only my hands are filmed), it would feel different.

Can you talk a bit more about this term ‘Person A’; what does that mean to you in your practice?

Recognising that everyone’s body is politically loaded and if you are recording a body, and showing it, you’re not neutral. To treat yourself as a body as neutral is a problem. There’s a long history of white people, in particular, treating themselves as the subject, whilst anyone who doesn’t conform to that is the ‘other’. That’s what I mean by Person A. That doesn’t mean I wouldn’t use my own body, and I definitely will use my body again, but it’s trying to have an awareness of that. The location of my body—which could also have been my body behind the camera, as well. It’s particularly poignant when it comes to representing your own body, I think. What do you think?

It’s incredibly hard to be the subject and analyser at the same time, but I think it’s also incredibly necessary. I’m curious about how to grapple with that problem myself.

I think it’s something that we grapple with and we try it out. There’s no set answer. Also, I feel I’ll probably make works and not always show them. I have a whole library full of performance films. They are little private performances and maybe they will become an archive of shorts at some point. But they’re more the performances that keep the practice going.

There’s an interesting relationship between filming and conservation. Filming, in a way, conserves a moment in time or a performance.

Absolutely. It’s a witnessing and, therefore, a recording of a witnessing. I use the word witnessing not to mean to live and experience, but to be a witness to something and to testify for its existence. Also, to consider that the camera is a witness and asking what makes the cut? What is burned in?

It could be argued that your practice is driven by concepts or forces that are clashing or rubbing up against each other in some way. Can you talk about that formula and what might be driving it? This method of pairing?

That’s something that has become more apparent in recent years from an interest in finding structural links between things. I do big mind maps, big drawings, where I know there’s some connection. For instance, the atom bomb rose project was about finding that material and knowing that there’s something in that I can’t quite figure out. There’s something violent within that plant that I don’t feel displaying that material as it is explains that. It’s about teasing out the hidden violences between/within things, or the hidden contradictions, when something seemingly benign is not necessarily what it seems. I think that’s something I’m kind of intrigued by at the moment. I have other ideas for projects that operate on a similar principle. Eventually, I’ll probably move in a different direction. Though I do think there’s something about placing two different, perhaps unexpected, materials together that has the opportunity to produce new knowledge in a nuanced way. Like basic montage theory—by placing two images together your mind makes its own narrative of what joins them. It creates a grey space where you can make your own conclusions between them.

Going back to Darling Darling, when an artwork has an environmental theme or an environmental critique or claim it often enters an interesting space of contradiction, in that the work comes with a level of waste or consumption associated with its production. Did that critique or problem come up for you and your work? And if so, how did you reason with it?

It’s very difficult to reason with. I flew to make this work. I flew twice – that’s contradictory and it’s anti-ethical. But I don’t feel that discounts, necessarily what the work is saying, because the work is not purely an environmental cry for conservation or care. It’s more of a scrutiny. It’s a way of scrutinising structures of care, structures of value, structures of hierarchy. It’s interesting, I was speaking with Charles Lawler, who is a technician at AGNSW about the work. He said he sat down and watched the work properly for the first time. The main thing that came out of it for him was how absurd the whole thing is. I really like his take on it, because we all end up being little cogs in this big machine of making and doing our little thing and carrying on with our little project. Much like the conservation side [of that work], we’re all doing our little tasks, doing our jobs—the absurdity of that, considering the destruction of the habitat that we need to survive in, the absurdity of us continuing on with our jobs, and how it can seem as if there’s very little way out. That’s not a cop out. I think it’s very difficult not to. I tried to be upfront with that in the work, in my own coded way. There’s a little SD card in the work which has been gold leafed. That was a way of wrapping myself up within the process and this art history—that I’m not separate from the art history that I’m critiquing. I’m not separate at all from the machine of art making that continues to be complicit in habitat destruction and world destruction and ideologies of damage. In this work, I’m trying to look at the structural issues underneath. Going forward, I will not be flying across the world to make work. But I guess for this work, to follow it through and to make it required some of that contradictory making. It’s a difficult question, though, because I feel conflicted about it.

It’s very human to have that sort of conflicted friction in the work.

I think it was also a surprise to me how resource heavy it is to make a work like that. The travel costs, the batteries for the camera, bringing a cinematographer out into far regional New South Wales, etc... all of these things that ended up being very resource heavy. I’m used to operating quite lightly, but still, you know, between different countries. It was a surprise to realise what it can take to make that sort of work. I was sceptical of that, whilst I was making I had doubts whether I was going about it in the right way. But I think we always have doubts when we’re making something in a way for the first time, and I’m really glad I followed through with it. I had a lot of amazing people to guide me, a wonderful team of collaborators and supporters, and friends who I asked for advice. Because I don’t think the work could actually express its message, if it was me and my camera. It would be a very different work. Maybe that’s okay, maybe I will make a very different work next time. It’s interesting—big, shiny moving image works come with a certain way of working. You can obviously break the mould and make them in your own way, but I feel that sometimes you’ve got to know the mould before you try and break it.

I’ll end on a lighter question. Are there any references in your career or artists that you keep coming back to when you’re making works? And from those influences (dead or alive), who would you invite to your next opening?

I feel they’ve changed a lot in recent years... Who would be yours?

I like the idea of Žižek turning up, perhaps getting drunk and spitting through his lisp at people, creating a bit of a scene in the gallery.

There’s an Italian director, who I really love at the moment, Alice Rohrwacher, who made the film Lazzaro Felice [Happy as Lazzaro]. I’ve been obsessed with that film for a while. It’s a surreal, magical realist, beautiful film. Her work is incredible.

My answer used to be someone like, Ragnar Kjartansson, because I really love his work. But I also don’t feel like I would really want that feedback... I think also, some really amazing artist friends—an artist called Andrea Canapa, who I met when I first went overseas. She lives in Berlin and is from Peru. We call one another and talk. Or Laura Hindmarsh… I think there’s about five artists, friends who I’ve had, who I call up regularly, and we talk through our issues, ideas, we work through what we’re working on, and ask: is this too provocative or not provocative enough? We care about one another’s practices and we’re not competitive. We care about one another. I actually feel, I know, this is a cheesy thing to say, but they’re the only people that I would want there.

It’s a rare, beautiful thing to have a community like that, where you are not competing.

Three of them are from German scenes, then there are people that I studied with. My Master’s course was called ‘Media Studies’, but a lot of it was performance. A lot of people hadn’t performed before and we were really vulnerable. Many of us did really uncertain performances as part of it. But when you do uncertain performances, you’re vulnerable in front of people. I remember doing a performance once in a shower. I wasn’t sure about it and I was really nervous. I did it twice in a shower at a public opening. The first time around, I thought, ‘oh, that really sucked’. Then the second time around, I looked up and three of my really close friends had come and it was this miserable night in the far end of deep South London. It made it. I think it’s those people that make it.

I have a friend who introduced me to making performance and she’s a performance artist with a capital P. A. She introduces herself as a performance artist. She’s from Estonia and studied Estonian performance art. She’s researched heavily into what performance art in that part of the world has meant politically and is the first person that I did a performance with, that would be considered as a performance. I asked, ‘can we do it when there’s not anyone around?’ I felt too vulnerable. So, we filmed it and that was a thrilling experience. I think that was a really pivotal moment—when someone said, ‘you can do this’. Then when I went to study in London, someone was putting on a performance art night within our cohort at a pub nearby. I did a performance of singing and I’d always been really scared to sing in public. But it felt like the right community, I could do that and be vulnerable, but also be okay. Another artist friend was there and she ended up doing a performance where she wore her pyjamas and rolled across the floor. Ever since then she has said, ‘oh, it was terrible’, but it wasn’t. It was a really great thing to put yourself in, we did things that made us really scared. The singing was terrible. I ended up going there and re-performing it later as a film, which has been the thing that’s been shown since then. But the actual performance at the spot was so vulnerable that I didn’t know what to think about it. I almost needed to make a film about it so that I could think about it. It’s those moments where you feel you have the support to actually make yourself vulnerable in that way and make the performance that you’re doing privately all the time in your practice and make it public to really push you.

If you are pushing all the time, if you’re nervous and you’re taking a risk, you might be doing something right. Something worth doing.

Exactly.

- To ‘capture’, in the context of this work, is to contain a location or an experience pictorially, to extract phenomena visually within a painted frame or the confined visual space of a camera’s lens.

About the interviewee:

Gabriella Hirst (she/her) was born and grew up on Cammeraygal land and is currently living between Berlin and London. She works primarily with moving image, performance, and with the garden as a site of critique and care. Gabriella’s practice and research explores connections between various manifestations of capture and control - spanning plant taxonomies, landscape painting, art conservation and nuclear history. Gabriella recently launched Darling Darling, the 2020 ACMI/Ian Potter Moving Image Commission, which is currently showing at ACMI and AGNSW. Her upcoming projects include An English Garden at Estuary 2021, Essex, and ‘Tip of the Iceberg’ at Focal Point Gallery, UK. Gabriella is currently an associate lecturer in Media Studies with the Royal College of Art, School of Architecture in London.

About the interviewer:

Jen Valender is an Australasian artist and writer from Aotearoa based in Narrm Melbourne whose practice-led research explores the relationship between moving image, sound and psyche. She uses cinematic devices, performance lectures and reflexive writing methods to sculpt undercurrents of relational ethics and poetic problematics that are surfacing in her practice. Jen is a recipient of the Next Wave Precinct Art Prize and the Ian Potter Museum Miegunyah Research Project Award. She holds a BA (Sociology) from Victoria University of Wellington, NZ and a BFA (Hons) from Monash University and the Victorian College of the Arts. Jen is currently an MFA (visual arts) research candidate at the VCA, University of Melbourne.

Currents is a collaboration between the Centre of Visual Art (CoVA) at the University of Melbourne and the School of Design, University of Western Australia, and is funded through the Schenberg International Arts Collaboration Program. The Advisory Board and Editorial Committee are comprised of staff and graduate students from across the University of Melbourne and the University of Western Australia.

Currents acknowledges the traditional owners and ongoing custodians of the land on which this journal is produced—the Boonwurung and Wurundjeri people of the Eastern Kulin Nation and Whadjuk people. We pay our respects to land, ancestors and Elders, and know that education involves working with their guidance to improve the lives of all.

ISSN 2652-8207

![]()

![]()

Currents acknowledges the traditional owners and ongoing custodians of the land on which this journal is produced—the Boonwurung and Wurundjeri people of the Eastern Kulin Nation and Whadjuk people. We pay our respects to land, ancestors and Elders, and know that education involves working with their guidance to improve the lives of all.

ISSN 2652-8207