A

Fugitive Subjectivity: Choi Yan Chi

蔡仞姿

and experimental art of Hong Kong,

1970-1989

Genevieve Trail

To cite this contribution:

Trail, Genevieve. ‘A Fugitive Subjectivity: Choi Yan Chi 蔡仞姿 and experimental art of Hong Kong, 1970-1989’. Currents Journal, Archipelagic Encounters (2021), https://currentsjournal.net/a-fugitive-subjectivity

Download this article ︎︎︎PDF

Keywords:

Hong Kong, performance art, Tian'anmen, 1997 handover, illegibility, indeterminacy, installation art, environmental art, structuralist theatre, postmodern dance, interdisciplinarity, cultural identity

Abstract: In July of 1989, artist Choi Yan Chi collaboratively staged a performance work entitled Object-act-ivities 東西遊戲.. Originally developed in order to investigate potential relationships between subjects and objects, such formal concerns were overnight made shallow and inadequate by the Tian’anmen Square Massacre of June 4, 1989, an event which clarified the full implications of the scheduled return of the territory’s sovereignty to mainland China in 1997. Subsequent to this event, the tone and nature of experimental art in Hong Kong shifted irrevocably, as artists began to reinvest in issues of local cultural identity. Choi's development up until this inflection point records the emergence of an artistic subjectivity that arose in Hong Kong during the 1970s-1980s, expressed in tendencies to deconstruction, anti-illusionism, interdisciplinarity and fragmentation and explored via new mediums of performance, video and environmental installation. Foregrounding this trajectory, this paper will argue that by the end of the 1980s, the fugitive and illegible expressions of subjectivity apparent in Choi's work, and more broadly characteristic of experimental art of the period, had been curtailed by the urgencies of Hong Kong’s political horizon and its demands for the coherent narration of Hong Kong as subject.

[Figure 5] Choi Yan Chi, Sabrina Mee Ying Fung, Sunny Pang, Willy Tsao, and Yoshiko Waki, As Slow As Possible: An Evening of Music Art Dance 慢之極 (maan zi gik), performance still, 1988. Courtesy of Choi Yan Chi.

Between 1986-1989, artist Choi Yan Chi

蔡仞姿 (b. 1949) collaboratively

staged three action-based works: Paintings by Choi Yan Chi and Works of Art

in Dialogue with Poetry and Dance 與蔡仞姿畫作的對話(梁秉鈞新詩 彭錦耀舞蹈)

(Pu Cai Jan-tsi waa tsok dik deoi waa (Loeng bing-gwan san si Paang Gam-jiu mou

dou) in 1986; As

Slow As Possible 慢之極(Maan tsi gik) in 1988, and lastly Object-act-ivities 東西遊戲 (Dung sai jau hei) in 1989. These events were characteristic

of the interdisciplinary and performance-led art that bloomed in Hong Kong

during this decade, initiated by the return of a generation of young

creatives who had studied overseas in Europe and North America. In Choi’s

trajectory from painting to installation and collaborative performance projects

it is possible to see a persistent interest in rendering the boundaries between

artwork and environment ambiguous, as well as employing performance as a means

to facilitate individuated, unscripted and candid encounters between people and

objects. Choi’s interests reflect a particular sensibility that emerged in Hong

Kong from the mid-to-late 1970s through the 1980s. At this time large numbers

of creatives engaged in a global discursive milieu sought to disentangle

themselves from an imperative to realise a local modernist vernacular that, from

the 1960s, had substantially been bound to the progressive revision or

reconfiguration of philosophies and aesthetics of Chinese painting 國畫

(gwok waa). Efforts to escape the burden of

producing an (internally and/or externally) legible cultural identity saw the emergence

of a loosely constellated set of aesthetic values often explored via new and

culturally detached mediums of performance, video, and installation. These can

be broadly characterised as tendencies to deconstruction, interdisciplinarity,

amateurism and the repudiation of narrative, illusion and expressionism. The

1980s saw a period of radical and formal experimental activities, the tone and

nature of which were shifted irrevocably by the events of June 4, 1989. Subsequently,

new uncertainties vis-à-vis Hong Kong’s scheduled return to China in 1997

compelled widespread re-engagement with issues of local cultural identity. This

paper engages with the works of Choi Yan Chi as a site to tentatively map an artistic

subjectivity and the conditions of its emergence and its dispersal, one which

can be differentiated both from earlier artistic desires for a local idiom contiguous

to the Chinese cultural tradition while being particular to Hong Kong, as well

as the later political turn of the 1990s with its investment in the establishment

of a coherent Hong Kong identity. The predominant art historical imperative to

narrate Hong Kong through the 1990s suggests that the urgencies of the

territory’s political horizon may have curtailed the development of a more

fragmented, decentralised and deliberately illegible site of subjectivity, as

the need for social and cultural cohesion bound such indeterminacy into Hong

Kong as subject.

Hong Kong is not well represented in global, or even regional art histories, in any period. Within contemporary art, the scant attention that the territory has received in large part coagulates around the 1997 ‘handover’ of Hong Kong’s sovereignty from Britain to the People’s Republic of Chine (PRC), an event which fixed Hong Kong as a postcolonial anomaly.1 It is a locale for which processes of ‘decolonisation’ following the end of British administration evolved entirely without the usual concomitant accretions of autonomy (with the effects of this disenfranchisement on the local populace now coming to the fore in alarming ways). Indeed, as art historian Lai Mei Lin has noted, ‘If not for the issue of the 1997 handover, Hong Kong art would have been neglected for much longer.’2 A desire to apprehend the type of cultural production that might emerge out of such a distinct historical context, however, has tended to produce an overreliance on socio-political factors as the causal mechanism for contemporary visual culture, rendering earlier periods of more apolitical artistic innovation effectively invisible. A frequently advanced position in critical and commercial discourses has been that prior to the period of self-reflection and narration that arose in the 1990s in response to the looming prospect of reabsorption into the mainland (described by Ackbar Abbas as the ‘immanence of its disappearance’3), nothing all that interesting was happening in Hong Kong. Writing on the role of China, Taiwan and Hong Kong in the development of global conceptual practice, art historian Gao Minglu, for example, suggests that with the sole exception of avant-garde theatre group Zuni Icosahedron, cultural production in Hong Kong over the 1970s-1980s offered a ‘bleak picture’.4 Choi’s work of this period refutes such a perspective, exemplifying the diffuse and networked uptake of collaborative experimentation in fields of music, poetry, dance, photography, video and theatre through the 1980s, in which the experimentation of Zuni was integral but not isolated.

The emergence of these newly collaborative performative forms was in no small part due to the significant number of young artists who returned to Hong Kong from having trained in various Euro-North American institutions in the late 1970s and early 1980s, a pedagogic sojourn made necessary by a lack of local tertiary offerings.5 A generation of artists, dancers, filmmakers and choreographers, including Josh Hon 韓偉康, Antonio Mak 麥顯揚, Yank Wong 黃仁逵, Wong Wo Bik 王禾璧, Oscar Ho Hing-kay何慶基, Johnson Chang Tsong-zung 張頌仁, Sunny Pang 彭錦耀, Willy Tsao 曹誠淵, and Michael Chen 陳贊雲, arrived to Hong Kong eager to ‘smash the frames’ of their own creative practices, and to establish a particular kind of artistic community amenable to their new experimental modes of creative expression.6 For many of these returning young artists, Hong Kong offered a kind of blank slate; an opportunity to start from ground zero in the development of a community and context for contemporary art. This is not to say that Hong Kong had been devoid of artistic experimentation prior to the 1980s.7 However, the practice and conceptualisation of what art was and how it might function remained in many ways preoccupied with the issue of Hong Kong’s cultural identity, circumscribed, as it had long been, by the imaginary of East meets West and expressed in various artistic attempts to either harmonise or reproduce this dialectical tension.8 Such concerns would re-emerge in ways far less constrained by either Eastern or Western cultural traditions in the 1990s in the face of Hong Kong’s political crises, expressed through installation work that engaged with specificities of place and material culture, as well as socially-engaged and activist forms of performance art. Generally disinterested in such identity-based concerns, if not seeking to actively circumvent them, these young artists arrived in Hong Kong eager to deconstruct the traditional boundaries between artistic disciplines and media that had remained stubbornly in place.

As a teacher in the early 1970s, Choi Yan Chi took evening classes with the highly influential ink painter Lui Shou-kwan 呂壽琨 (1919-75). With his encouragement she moved to the United States in 1972 to pursue an education in art. Studying at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), from 1974-78, Choi is reported to have been proximate to both feminist and performance traditions, attending lectures and viewing works by the likes of Marcia Tucker, Judy Chicago, Laurie Anderson, Lucy Lippard and Chris Burden.9 However, she seems to have remained somewhat constrained by a matrix of expectations whereby her American teachers and colleagues demanded, on the one hand, the performance of a repressed Asian femininity, and on the other that she denude her works of any culturally specific markers in order to achieve a kind of “universalism” compelled by Modernism’s formal purity.10 At the same time, Choi grappled with a sense of cultural duty to the perpetuation of Chinese aesthetics, taking it as a personal ‘responsibility’ to ‘help steer Chinese contemporary art in certain directions’.11 Such feelings of obligation were undoubtedly an inheritance from senior generations of Hong Kong artists who, from the 1950s, began to be engrossed by efforts to realise a modern idiom indigenous to Hong Kong, culturally resourced by the Chinese civilisation from which the majority of them heralded, and enriched by Hong Kong’s cosmopolitan cultural milieu.12 The search for an art form particular to Hong Kong saw the proliferation of artist groups and societies through the 1960s, as artists took up positions on the aesthetic and philosophical principles by which Chinese art should be modernised and renewed into the future. The competing approaches adopted by artists to address the issue of how to make the forms and tenets of Chinese art both locally and internationally relevant manifested in differentiated positions on the significance of material-versus-conceptual continuity, as well as the manner by which to incorporate Chinese and Western signifiers, with disjunction/difference variously harmonised or accentuated.13 Of course, not all artists at this time were working in ink, nor were they necessarily all equally preoccupied with these issues. However, the New Ink Painting Movement, led by Lui Shou Kwan and ascendent within the Hong Kong Museum of Art was nevertheless the zeitgeist of the 1960s and 1970s, central to the construction of a local art genealogy.

Although Choi was interested in engaging with some of the conceptual elements of Chinese painting (her works, even through the 1980s, feature obscured Chinese script, and in some cases utilise a format that intimates the hanging scroll of traditional Chinese painting) she was inhospitable to the use of materials that might explicitly rehearse an essentialised cultural identity. Choi reports that she became exhausted by the efforts of artists such as Lui Shou-kwan and those associated with the New Ink Painting Movement, perceiving their ink revivalism as a kind of root-finding cultural nationalism.14 In a similar vein, she felt the work of the numerous Chicago Imagists associated with the SAIC during her time there to be somewhat distasteful; a group that co-opted the space of the canvas for the ‘boorish’ and ‘unrestrained’ venting of personal emotion.15

![]()

[Figure 1] Choi Yan Chi, Summer 夏 (haa), 1975, paint and plastic sheeting, dimensions unknown. Courtesy of the artist.

Against such identarian and neo-expressionist concerns, Choi began to work in a more minimalist fashion. By removing representational content from her work and leveraging the cultural indeterminacy of mediums such as silk screen and photography, Choi sought to emancipate herself from an impulse to use each new piece of information or idea as an augmentation of the Chinese cultural tradition.16 Nevertheless she recalls being criticised for the inclusion of Chinese script within her work as an element illegible to her American colleagues.17 Influenced by the silkscreen and combine paintings of Robert Rauschenberg that she had seen in the early 1970s, Choi completed Summer 夏 (haa) [Figure 1] in 1975. Choi used Rauschenberg’s image transfer technique to work directly onto the wall, before covering the entire space of the work with plastic sheeting, which she then worked on further.18 In other works of the same period, Choi applied plaster to the wall to literally build a painting up from its support, or, as in Erosion III (1976) punched a hole through the painting and into the wall, conjoining the work with its structural support.19 Summer was the first work that Choi had been able to complete since she had arrived in Chicago in 1974.20 This breakthrough precipitated her series ‘From the Wall to the Floor’, a title clearly explicating her desire to liberate mark making from the rectilinear constraints of its conventional frame. In Summer, the lack of any framing device and the simultaneous presence within the work of layers that are both literally on the wall, and off or on top of it, are embryonic manifestations of an interest in the relationship between the artwork and its context. These interests continued to preoccupy Choi throughout her career and would be encouraged by the similarly deconstructive concerns of her collaborators upon her return to Hong Kong.

![]()

![]() [Figure 2]

Choi Yan Chi, Light and Shadow 山中拾掇 (saan zung sap zyut), 1985, wood, paint and fabric, dimensions variable.

Installation view, An Extension into Space, Hong Kong Arts Centre, 1985. Courtesy of the artist.

[Figure 2]

Choi Yan Chi, Light and Shadow 山中拾掇 (saan zung sap zyut), 1985, wood, paint and fabric, dimensions variable.

Installation view, An Extension into Space, Hong Kong Arts Centre, 1985. Courtesy of the artist.

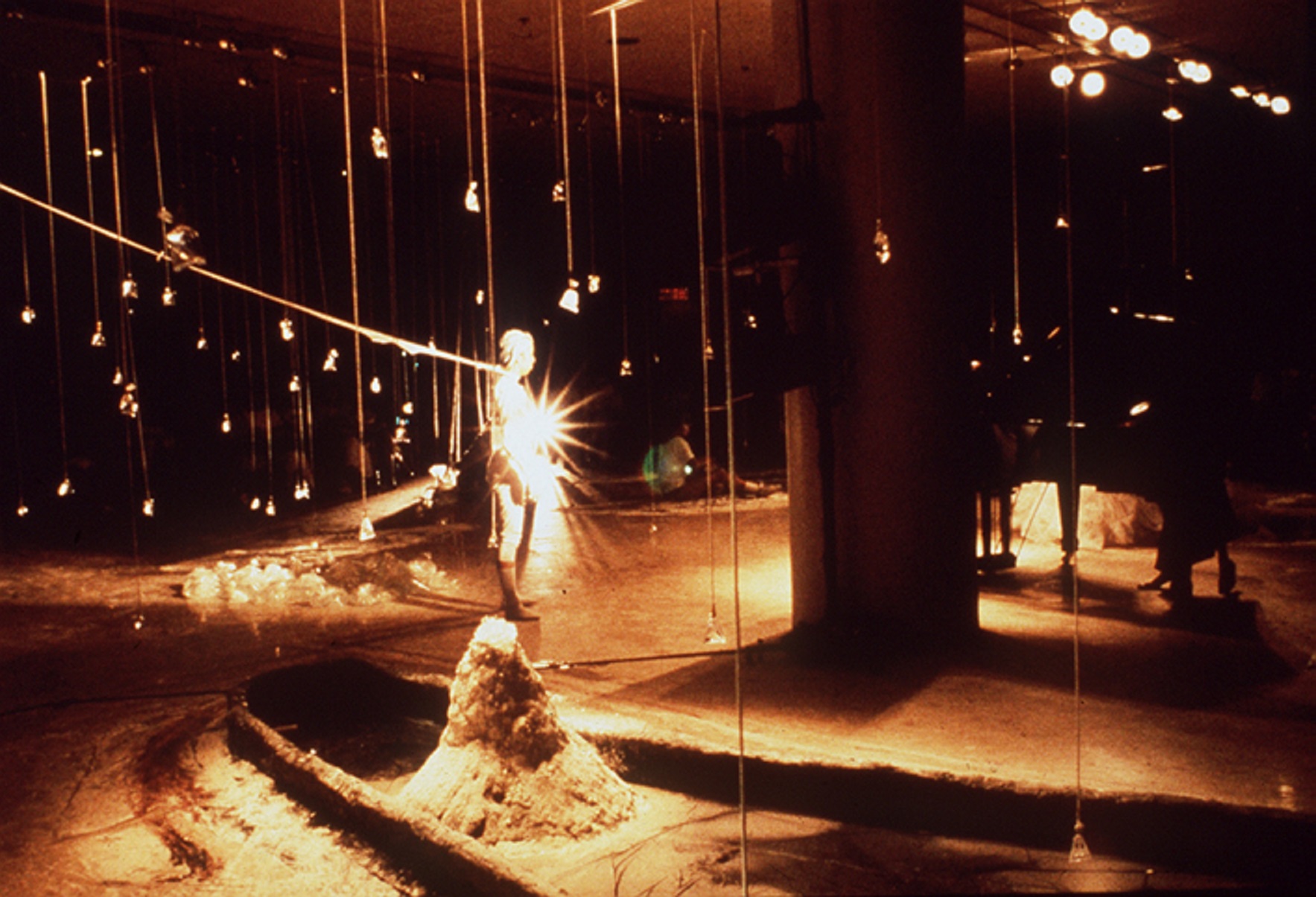

A decade later, Choi had returned to Hong Kong and had directed her attention to environmental installation. In 1985 the Hong Kong Arts Centre held a solo exhibition of her work, An Extension into Space 空間內外(hung gaan noi ngoi), a first for the Arts Centre. In fact, so novel was the prospect of an exhibition of installation art of this scale in Hong Kong that Choi recalls the curators working to figure out the appropriate translation from the English word “installation” into Chinese script (装置 tsong tsi) in the lead up to the show.21 For the exhibition Choi created three site-specific installations: Stepping into a Space 形彩之外 (jing choi tsi ngoi), Light and Shadow 山中拾掇 (saan tsung sap uyut)[Figure 2],andLight Adventure 光影樂(gwong ying lok) [Figure 3]. Employing distinct formal strategies, each work leveraged the material qualities of constituent elements (mirrors, gauze, slides and fragmented timber) to activate their surroundings; variously dilating, rupturing, splitting, refracting, and doubling space. The installations thereby displaced or removed the discrete boundaries of the traditional art object and reconfigured the artwork as a spatial environment, with the viewer fully implicated within the parameters of the work. Within these installations, the audience is acknowledged as an active and generative participant in the construction of space. Speaking of Light and Shadow, for example, Choi expressed an explicit interest in reversing the traditional roles of artwork and spectator as they are typically construed within theatre or performance by creating a work in which perception actively fluctuates in relation to the mobility of the viewer rather than that of the artwork.22 Materials are recognised as able to in themselves affect, engender, or immerse an audience. This is in keeping with Choi’s own definition of environmental art as that in which ‘the viewer is involved in the space of lighting, sound, and colour, and the spirit and body are integrated into the surrounding environment.’23 The emphasis on visual contingency as provoked by the material qualities of the works means that each installation is experienced specifically and variably, based on the position of the individual. The absence of representational content reinforces this differentiated effect. Possibilities are suggested, but the meaning of the work ultimately remains indeterminate. Lacking any didactic element, the environmental installations provide a generic space which can be tabulated against individual encounters. In this way, the works of An Extension into Space circumvent universal or universalising meaning in a manner that is perhaps reflective of Choi’s own rejection of expectations that art be used as a vehicle for the expression of a coherent identity or narrative, experienced both in Hong Kong and in the U.S.

![]()

[Figure 3] Choi Yan Chi, Light Adventure 光影樂 (gwong jing lok), 1985, mirror, dimensions unknown. Installation view, An Extension into Space, Hong Kong Arts Centre, 1985. Courtesy of the artist.

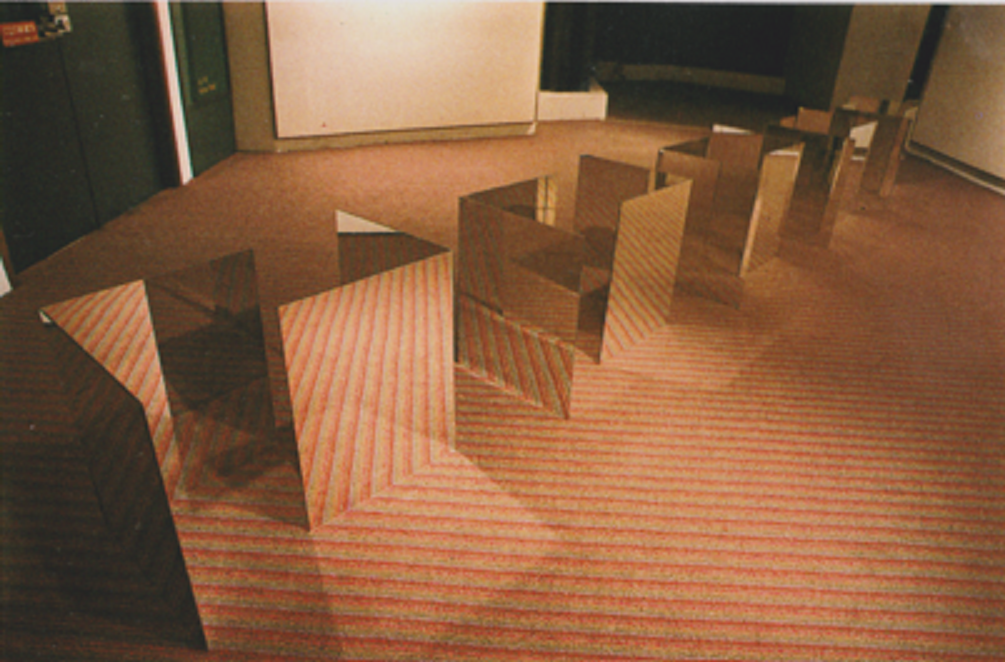

The development of Choi’s principles of movement and immersion that are expressed within these installation works of 1985 can be credited in part to her involvement with the experimental theatre group Zuni Icosahedron from 1980 onwards. Founded in 1982 by Danny Yung 榮念曾 and James Wong 王銳顯, Zuni worked at the intersection of performance, video, sound, and installation, and were significant in providing an open and experimental context in which artists were able to collaborate, as well as orienting artists towards elements of space, time, and movement. At the invitation of Danny Yung, Choi contributed a theatre installation to Part III: Questions of a four-part cycle of structuralist theatre events titled Journey to the East 中國旅程: 問題 (tsung gwok leoi cing: man tai) [Figure 4], written by Yung and staged at the Hong Kong Arts Centre over 1980-81. For this work, Choi constructed moveable gauze screens onto which she projected slides and drawings by artist Yank Wong, which together formed a translucent and layered environment for dancers from the recently formed City Contemporary Dance Company (CCDC). Journey to the East was a collaboration between over twenty young artists from various disciplines and is significant as both the ‘the earliest local presentation of non-textual/non-narrative conceptual performance’ in Hong Kong, as well as the first large-scale example of what was to become an enduring interest in interdisciplinary and performance-based art events in the territory through the 1980s in particular.24 Journey to the East, described by academic Rosella Ferrari as an ‘assemblage of visual and aural signifiers of the PRC’25, deployed a range of episodes, images, and symbols drawn from contemporaneous news events and cultural forms from Hong Kong as well as China. These were not used as a source of narrative content but rather formed a disjointed set of images, words and points of reference that aimed to produce variegated and idiosyncratic projective associations.26 While this content could easily be read as related to the 1997 handover, the discussion of which began in the early 1980s with Margaret Thatcher’s visit to Beijing in 1982 to meet with then-leader Deng Xiaoping, it may also have been motivated by study tours of Hong Kong artists to mainland China that had become relatively commonplace by the early 1980s, ushering in a period of anachronistic nostalgia for the mainland. The performance cycle, which radically deconstructed compositional norms of theatrical performance in order to interrogate its purpose and parameters, disassembled elements of time, space, gesture, dialogue, monologue, and audience, isolating and detaching them from any organising schema of theme or plotline in order to allow for the clear observation of the characteristics of a single constituent element, as well as the effect of their variable combinations. Sentences strung together in structures that superficially resemble conventions of monologue and dialogue were generally unconnected by meaning, which deliberately pulled the audience out of the world of the work to signpost what was happening on stage (‘I am now ready to stand up and walk into the frame to complete the work’); or they described recent banal events in a straightforward manner (‘On November 7th last year, in the small theatre of the Arts Centre, a person was sleeping on the ground. It was very dark, and noticeably quiet…some aeroplane sounds’); or lectured the audience on issues related to art (‘Modern people accept, or are forced to accept, the image of an artist, that is, an artist has absolute freedom and the absolute right to do things intuitively…’).27 Instead of delivering a plot line, message or lesson, the performance elements, in particular the use of projected photographic slides, text and audio recorded voiceover, aimed to produce resonances in the audience, opening out a conceptual space within the work for the associating minds of viewers to expand into. Such a structure constituted a differentiated invitation to complete the work, obliging audience members to actively work to relate the elements to each other, as well as to their own memory. Sequential elements unlinked except for their co-occurrence in time and space also required the audience to continuously shift their attention, emulating the cognitive experience of the “real world”, and making them deliberately aware of the means by which the work aimed to elicit a reaction rather than sublimating this manipulation into plot. Journey to the East prototyped a number of tendencies that would come to characterise performance art through the 1980s, and which Choi would also take up, namely the use of video and installation as theatrical sets; literal, non-virtuosic and non-expressive movements; and a deconstruction or deferral of didactic meaning through non-linear and anti-narrative scripting. Many of these features drew heavily from postmodern dance of the 1960s to 1980s, an approach to dance portended by the work of Merce Cunningham, and broadly characterised by Roger Copeland in 1983 as ‘works that utilize pedestrian, unstylized, or found movement; works that can be successfully performed by people who possess no formal dance training; works that conceive of choreography as the execution of a "task" assigned to the performer, works that are rigorously anti-illusionistic; and works that unfold in objective or clock-time rather than a theatrically-condensed or musically-abstract time.’28 In Zuni’s works, however, movement is so generic and so pedestrian as to make ‘dance’ a somewhat irrelevant term.

![]()

[Figure 4] Zuni Icosahedron, Journey to the East: Questions中國旅程: 問題 (tsung gwok leoi cing: man tai), performance stills, 1980. Courtesy of Choi Yan Chi.

Hong Kong is not well represented in global, or even regional art histories, in any period. Within contemporary art, the scant attention that the territory has received in large part coagulates around the 1997 ‘handover’ of Hong Kong’s sovereignty from Britain to the People’s Republic of Chine (PRC), an event which fixed Hong Kong as a postcolonial anomaly.1 It is a locale for which processes of ‘decolonisation’ following the end of British administration evolved entirely without the usual concomitant accretions of autonomy (with the effects of this disenfranchisement on the local populace now coming to the fore in alarming ways). Indeed, as art historian Lai Mei Lin has noted, ‘If not for the issue of the 1997 handover, Hong Kong art would have been neglected for much longer.’2 A desire to apprehend the type of cultural production that might emerge out of such a distinct historical context, however, has tended to produce an overreliance on socio-political factors as the causal mechanism for contemporary visual culture, rendering earlier periods of more apolitical artistic innovation effectively invisible. A frequently advanced position in critical and commercial discourses has been that prior to the period of self-reflection and narration that arose in the 1990s in response to the looming prospect of reabsorption into the mainland (described by Ackbar Abbas as the ‘immanence of its disappearance’3), nothing all that interesting was happening in Hong Kong. Writing on the role of China, Taiwan and Hong Kong in the development of global conceptual practice, art historian Gao Minglu, for example, suggests that with the sole exception of avant-garde theatre group Zuni Icosahedron, cultural production in Hong Kong over the 1970s-1980s offered a ‘bleak picture’.4 Choi’s work of this period refutes such a perspective, exemplifying the diffuse and networked uptake of collaborative experimentation in fields of music, poetry, dance, photography, video and theatre through the 1980s, in which the experimentation of Zuni was integral but not isolated.

The emergence of these newly collaborative performative forms was in no small part due to the significant number of young artists who returned to Hong Kong from having trained in various Euro-North American institutions in the late 1970s and early 1980s, a pedagogic sojourn made necessary by a lack of local tertiary offerings.5 A generation of artists, dancers, filmmakers and choreographers, including Josh Hon 韓偉康, Antonio Mak 麥顯揚, Yank Wong 黃仁逵, Wong Wo Bik 王禾璧, Oscar Ho Hing-kay何慶基, Johnson Chang Tsong-zung 張頌仁, Sunny Pang 彭錦耀, Willy Tsao 曹誠淵, and Michael Chen 陳贊雲, arrived to Hong Kong eager to ‘smash the frames’ of their own creative practices, and to establish a particular kind of artistic community amenable to their new experimental modes of creative expression.6 For many of these returning young artists, Hong Kong offered a kind of blank slate; an opportunity to start from ground zero in the development of a community and context for contemporary art. This is not to say that Hong Kong had been devoid of artistic experimentation prior to the 1980s.7 However, the practice and conceptualisation of what art was and how it might function remained in many ways preoccupied with the issue of Hong Kong’s cultural identity, circumscribed, as it had long been, by the imaginary of East meets West and expressed in various artistic attempts to either harmonise or reproduce this dialectical tension.8 Such concerns would re-emerge in ways far less constrained by either Eastern or Western cultural traditions in the 1990s in the face of Hong Kong’s political crises, expressed through installation work that engaged with specificities of place and material culture, as well as socially-engaged and activist forms of performance art. Generally disinterested in such identity-based concerns, if not seeking to actively circumvent them, these young artists arrived in Hong Kong eager to deconstruct the traditional boundaries between artistic disciplines and media that had remained stubbornly in place.

As a teacher in the early 1970s, Choi Yan Chi took evening classes with the highly influential ink painter Lui Shou-kwan 呂壽琨 (1919-75). With his encouragement she moved to the United States in 1972 to pursue an education in art. Studying at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), from 1974-78, Choi is reported to have been proximate to both feminist and performance traditions, attending lectures and viewing works by the likes of Marcia Tucker, Judy Chicago, Laurie Anderson, Lucy Lippard and Chris Burden.9 However, she seems to have remained somewhat constrained by a matrix of expectations whereby her American teachers and colleagues demanded, on the one hand, the performance of a repressed Asian femininity, and on the other that she denude her works of any culturally specific markers in order to achieve a kind of “universalism” compelled by Modernism’s formal purity.10 At the same time, Choi grappled with a sense of cultural duty to the perpetuation of Chinese aesthetics, taking it as a personal ‘responsibility’ to ‘help steer Chinese contemporary art in certain directions’.11 Such feelings of obligation were undoubtedly an inheritance from senior generations of Hong Kong artists who, from the 1950s, began to be engrossed by efforts to realise a modern idiom indigenous to Hong Kong, culturally resourced by the Chinese civilisation from which the majority of them heralded, and enriched by Hong Kong’s cosmopolitan cultural milieu.12 The search for an art form particular to Hong Kong saw the proliferation of artist groups and societies through the 1960s, as artists took up positions on the aesthetic and philosophical principles by which Chinese art should be modernised and renewed into the future. The competing approaches adopted by artists to address the issue of how to make the forms and tenets of Chinese art both locally and internationally relevant manifested in differentiated positions on the significance of material-versus-conceptual continuity, as well as the manner by which to incorporate Chinese and Western signifiers, with disjunction/difference variously harmonised or accentuated.13 Of course, not all artists at this time were working in ink, nor were they necessarily all equally preoccupied with these issues. However, the New Ink Painting Movement, led by Lui Shou Kwan and ascendent within the Hong Kong Museum of Art was nevertheless the zeitgeist of the 1960s and 1970s, central to the construction of a local art genealogy.

Although Choi was interested in engaging with some of the conceptual elements of Chinese painting (her works, even through the 1980s, feature obscured Chinese script, and in some cases utilise a format that intimates the hanging scroll of traditional Chinese painting) she was inhospitable to the use of materials that might explicitly rehearse an essentialised cultural identity. Choi reports that she became exhausted by the efforts of artists such as Lui Shou-kwan and those associated with the New Ink Painting Movement, perceiving their ink revivalism as a kind of root-finding cultural nationalism.14 In a similar vein, she felt the work of the numerous Chicago Imagists associated with the SAIC during her time there to be somewhat distasteful; a group that co-opted the space of the canvas for the ‘boorish’ and ‘unrestrained’ venting of personal emotion.15

[Figure 1] Choi Yan Chi, Summer 夏 (haa), 1975, paint and plastic sheeting, dimensions unknown. Courtesy of the artist.

Against such identarian and neo-expressionist concerns, Choi began to work in a more minimalist fashion. By removing representational content from her work and leveraging the cultural indeterminacy of mediums such as silk screen and photography, Choi sought to emancipate herself from an impulse to use each new piece of information or idea as an augmentation of the Chinese cultural tradition.16 Nevertheless she recalls being criticised for the inclusion of Chinese script within her work as an element illegible to her American colleagues.17 Influenced by the silkscreen and combine paintings of Robert Rauschenberg that she had seen in the early 1970s, Choi completed Summer 夏 (haa) [Figure 1] in 1975. Choi used Rauschenberg’s image transfer technique to work directly onto the wall, before covering the entire space of the work with plastic sheeting, which she then worked on further.18 In other works of the same period, Choi applied plaster to the wall to literally build a painting up from its support, or, as in Erosion III (1976) punched a hole through the painting and into the wall, conjoining the work with its structural support.19 Summer was the first work that Choi had been able to complete since she had arrived in Chicago in 1974.20 This breakthrough precipitated her series ‘From the Wall to the Floor’, a title clearly explicating her desire to liberate mark making from the rectilinear constraints of its conventional frame. In Summer, the lack of any framing device and the simultaneous presence within the work of layers that are both literally on the wall, and off or on top of it, are embryonic manifestations of an interest in the relationship between the artwork and its context. These interests continued to preoccupy Choi throughout her career and would be encouraged by the similarly deconstructive concerns of her collaborators upon her return to Hong Kong.

A decade later, Choi had returned to Hong Kong and had directed her attention to environmental installation. In 1985 the Hong Kong Arts Centre held a solo exhibition of her work, An Extension into Space 空間內外(hung gaan noi ngoi), a first for the Arts Centre. In fact, so novel was the prospect of an exhibition of installation art of this scale in Hong Kong that Choi recalls the curators working to figure out the appropriate translation from the English word “installation” into Chinese script (装置 tsong tsi) in the lead up to the show.21 For the exhibition Choi created three site-specific installations: Stepping into a Space 形彩之外 (jing choi tsi ngoi), Light and Shadow 山中拾掇 (saan tsung sap uyut)[Figure 2],andLight Adventure 光影樂(gwong ying lok) [Figure 3]. Employing distinct formal strategies, each work leveraged the material qualities of constituent elements (mirrors, gauze, slides and fragmented timber) to activate their surroundings; variously dilating, rupturing, splitting, refracting, and doubling space. The installations thereby displaced or removed the discrete boundaries of the traditional art object and reconfigured the artwork as a spatial environment, with the viewer fully implicated within the parameters of the work. Within these installations, the audience is acknowledged as an active and generative participant in the construction of space. Speaking of Light and Shadow, for example, Choi expressed an explicit interest in reversing the traditional roles of artwork and spectator as they are typically construed within theatre or performance by creating a work in which perception actively fluctuates in relation to the mobility of the viewer rather than that of the artwork.22 Materials are recognised as able to in themselves affect, engender, or immerse an audience. This is in keeping with Choi’s own definition of environmental art as that in which ‘the viewer is involved in the space of lighting, sound, and colour, and the spirit and body are integrated into the surrounding environment.’23 The emphasis on visual contingency as provoked by the material qualities of the works means that each installation is experienced specifically and variably, based on the position of the individual. The absence of representational content reinforces this differentiated effect. Possibilities are suggested, but the meaning of the work ultimately remains indeterminate. Lacking any didactic element, the environmental installations provide a generic space which can be tabulated against individual encounters. In this way, the works of An Extension into Space circumvent universal or universalising meaning in a manner that is perhaps reflective of Choi’s own rejection of expectations that art be used as a vehicle for the expression of a coherent identity or narrative, experienced both in Hong Kong and in the U.S.

[Figure 3] Choi Yan Chi, Light Adventure 光影樂 (gwong jing lok), 1985, mirror, dimensions unknown. Installation view, An Extension into Space, Hong Kong Arts Centre, 1985. Courtesy of the artist.

The development of Choi’s principles of movement and immersion that are expressed within these installation works of 1985 can be credited in part to her involvement with the experimental theatre group Zuni Icosahedron from 1980 onwards. Founded in 1982 by Danny Yung 榮念曾 and James Wong 王銳顯, Zuni worked at the intersection of performance, video, sound, and installation, and were significant in providing an open and experimental context in which artists were able to collaborate, as well as orienting artists towards elements of space, time, and movement. At the invitation of Danny Yung, Choi contributed a theatre installation to Part III: Questions of a four-part cycle of structuralist theatre events titled Journey to the East 中國旅程: 問題 (tsung gwok leoi cing: man tai) [Figure 4], written by Yung and staged at the Hong Kong Arts Centre over 1980-81. For this work, Choi constructed moveable gauze screens onto which she projected slides and drawings by artist Yank Wong, which together formed a translucent and layered environment for dancers from the recently formed City Contemporary Dance Company (CCDC). Journey to the East was a collaboration between over twenty young artists from various disciplines and is significant as both the ‘the earliest local presentation of non-textual/non-narrative conceptual performance’ in Hong Kong, as well as the first large-scale example of what was to become an enduring interest in interdisciplinary and performance-based art events in the territory through the 1980s in particular.24 Journey to the East, described by academic Rosella Ferrari as an ‘assemblage of visual and aural signifiers of the PRC’25, deployed a range of episodes, images, and symbols drawn from contemporaneous news events and cultural forms from Hong Kong as well as China. These were not used as a source of narrative content but rather formed a disjointed set of images, words and points of reference that aimed to produce variegated and idiosyncratic projective associations.26 While this content could easily be read as related to the 1997 handover, the discussion of which began in the early 1980s with Margaret Thatcher’s visit to Beijing in 1982 to meet with then-leader Deng Xiaoping, it may also have been motivated by study tours of Hong Kong artists to mainland China that had become relatively commonplace by the early 1980s, ushering in a period of anachronistic nostalgia for the mainland. The performance cycle, which radically deconstructed compositional norms of theatrical performance in order to interrogate its purpose and parameters, disassembled elements of time, space, gesture, dialogue, monologue, and audience, isolating and detaching them from any organising schema of theme or plotline in order to allow for the clear observation of the characteristics of a single constituent element, as well as the effect of their variable combinations. Sentences strung together in structures that superficially resemble conventions of monologue and dialogue were generally unconnected by meaning, which deliberately pulled the audience out of the world of the work to signpost what was happening on stage (‘I am now ready to stand up and walk into the frame to complete the work’); or they described recent banal events in a straightforward manner (‘On November 7th last year, in the small theatre of the Arts Centre, a person was sleeping on the ground. It was very dark, and noticeably quiet…some aeroplane sounds’); or lectured the audience on issues related to art (‘Modern people accept, or are forced to accept, the image of an artist, that is, an artist has absolute freedom and the absolute right to do things intuitively…’).27 Instead of delivering a plot line, message or lesson, the performance elements, in particular the use of projected photographic slides, text and audio recorded voiceover, aimed to produce resonances in the audience, opening out a conceptual space within the work for the associating minds of viewers to expand into. Such a structure constituted a differentiated invitation to complete the work, obliging audience members to actively work to relate the elements to each other, as well as to their own memory. Sequential elements unlinked except for their co-occurrence in time and space also required the audience to continuously shift their attention, emulating the cognitive experience of the “real world”, and making them deliberately aware of the means by which the work aimed to elicit a reaction rather than sublimating this manipulation into plot. Journey to the East prototyped a number of tendencies that would come to characterise performance art through the 1980s, and which Choi would also take up, namely the use of video and installation as theatrical sets; literal, non-virtuosic and non-expressive movements; and a deconstruction or deferral of didactic meaning through non-linear and anti-narrative scripting. Many of these features drew heavily from postmodern dance of the 1960s to 1980s, an approach to dance portended by the work of Merce Cunningham, and broadly characterised by Roger Copeland in 1983 as ‘works that utilize pedestrian, unstylized, or found movement; works that can be successfully performed by people who possess no formal dance training; works that conceive of choreography as the execution of a "task" assigned to the performer, works that are rigorously anti-illusionistic; and works that unfold in objective or clock-time rather than a theatrically-condensed or musically-abstract time.’28 In Zuni’s works, however, movement is so generic and so pedestrian as to make ‘dance’ a somewhat irrelevant term.

[Figure 4] Zuni Icosahedron, Journey to the East: Questions中國旅程: 問題 (tsung gwok leoi cing: man tai), performance stills, 1980. Courtesy of Choi Yan Chi.

The active questioning and

dialogic context in which Journey to the East was developed encapsulates

the energetic desire of this period to expand the boundaries of what might be

considered art, and the role of intermedia collaboration as a tool towards this

effort. Of Journey to the East Choi recalls that ‘heated arguments and

discussions were aroused over artistic approaches, directions and ideologies’ and

that ‘questions on the relationship between art and audience, society and the

establishment were put forth for discussions.’29 Choi was

intrigued by the use of movement and space, and by the way in which the

performers were forced to adjust their own work in response to the addition of

her installations as an element within the piece. Such lines of enquiry fed

into Choi’s existing concerns with environments and spatialisation, directing her

attention towards the potential of interdisciplinary collaboration as a means

to bring her work more fully into a spatial and temporal register. Her

subsequent movements into installation art proper, as well as, as we will see,

a kind of performance art that centred on unscripted and idiosyncratic phenomenological

encounters between bodies and objects, position her experiments with

collaboration and open horizontal exchange in the context of theatre as central

to her own artistic development as well as to that of installation and

performance art in the territory more generally.

Action-based Works, 1986-1989

In the late 1980s, Choi began to develop action-based events, as her efforts to spatialise the painting field became translated into more embodied forms. In 1986, she staged Paintings by Choi Yan Chi and Works of Art in Dialogue with Poetry and Dance, creating artworks in response to the poetry of Leung Ping-kwan 梁秉鈞, which were in turn activated by the dance of Sunny Pang. Two years later, in 1988, she collaborated on As Slow As Possible (慢之極 maan zi gik): An Evening of Music Art Dance [Figure 5]at the invitation of pianist Sabrina Mee Ying Fung 馮美瑩, and with dancers and choreographers Sunny Pang, Willy Tsao, and Yoshiko Waki. The performance’s title is in reference to eponymous piece of music by Fluxus composer John Cage, ASLSP, a work for piano written in 1985, and reworked for the organ in 1987. In Cage’s original composition, the title ASLSP stands for ‘As Slow(ly) and Soft(ly) as Possible’, and aside from this broadly inaugurating instruction, dynamics and tempo are free.30 The event was offered as a tribute to water, a thematic reflected in the installation items which included small plastic bags of water (the kind used to transport fish), a concrete well, and a television continuously screening water related imagery. A block of ice marked time as it melted. Choi also contributed a pile of white gauze, which, in an escalation of her previous use of the material, performers interacted with as a now completely disassembled painterly surface. This clear invocation of Cage’s work decisively indicates Choi’s interest in his aesthetic philosophy, in particular his elevation of environmental and ambient sound and compositional processes of chance and indeterminacy. Cage, was of course, also intrinsic to the development of postmodern dance through his longstanding collaboration with Cunningham. Cage had given a lecture at the SAIC in October of 1977 while Choi was a student there and it is feasible to assume that she attended.31 Unfortunately, due to the paucity of material documenting this period of Choi’s life, the specificities of her intellectual encounters remain, at this stage of research, somewhat speculative. In any case, she would certainly have been exposed to his, as well as other Fluxus theories during her time in Chicago. A far more direct link to Cage’s work emerges through the involvement of avant-garde pianist Sabrina Fung, who, having studied in Vienna and Canada, moved to New York with Andrew Culver in the late 1970s in order to get to know Cage. Culver, who Fung later married, was Cage’s creative assistant for eleven years and visited Hong Kong on a number of occasions.32

Choi and her collaborators were interested in producing a structuring architecture within which performers were free to elaborate idiosyncratic gestures that would exist as generative building blocks comprising the larger event. Although a number of predetermined elements (namely the musical score and the installation that formed the performance environment) tabulated the work, within these parameters a high degree of lateral autonomy was afforded. Individual performers existed as independent and dispersed elements that were nevertheless responding to and encountering each other within a common set of environmental inputs. Such a model respects the integrity of the individual as a discrete entity endowed with agency, but nevertheless understands the individual ultimately as a sociable element whose relational instantiation makes them susceptible to influence and variation in response to an encounter with other elements. Individuals are pliable, maintaining their own boundaries whilst also being open to vision and suggestion as the work progresses. This is a playful model not dissimilar to that of the Fluxus art-game, which ‘gives the rules without the exact details’, instead offering a ‘range of possibilities’ in order to respect both the factor of chance and the agency of actors.33 Choi deliberately selected objects for installation that she felt lent themselves to such activation and play by performers. Crucially, by declining to script relationships between individuals and things, the work remained open to an infinite number of chance interpenetrations and evolutions.34 This duality of structure and improvisation or impromptu-ness alludes to Cage’s practice of constructing ‘freedom within limitations’, as seen in compositions in which the temporal arrangement was pre-set and the content left indeterminate, or vice versa with precise sonic materials provided but their usage left open to interpretation by other actors.35 Choi may also have been influenced by the visual scores of Zuni Icosahedron which, similarly, made use of precise time slots or intervals in order to demarcate different sections of the work. In comparison to Journey to the East, however, in Choi’s performance works objects played a far more significant role, at least equal to that of the performers. Significantly, the process-based and indeterminate nature of such a model necessarily relies on a heightened awareness of fellow participants and their actions. A requisite form of intersubjective attention that works to bind actors in an ecology of feedback, as the progression of the event hinges on each being attuned and open to the gestural propositions of others, and equally, to environmental elements of object and sound that surround them.

![]()

[Figure 6] Choi Yan Chi, Chiang Afa, Kung Chishing, Lau Chingping, Leung Mantao, Leung Pingkwan, Mui Cheukyin and Yau Ching, Object-act-ivities 東西遊戲 (dung sai jau hei), performance still, 1989. Courtesy of Choi Yan Chi.

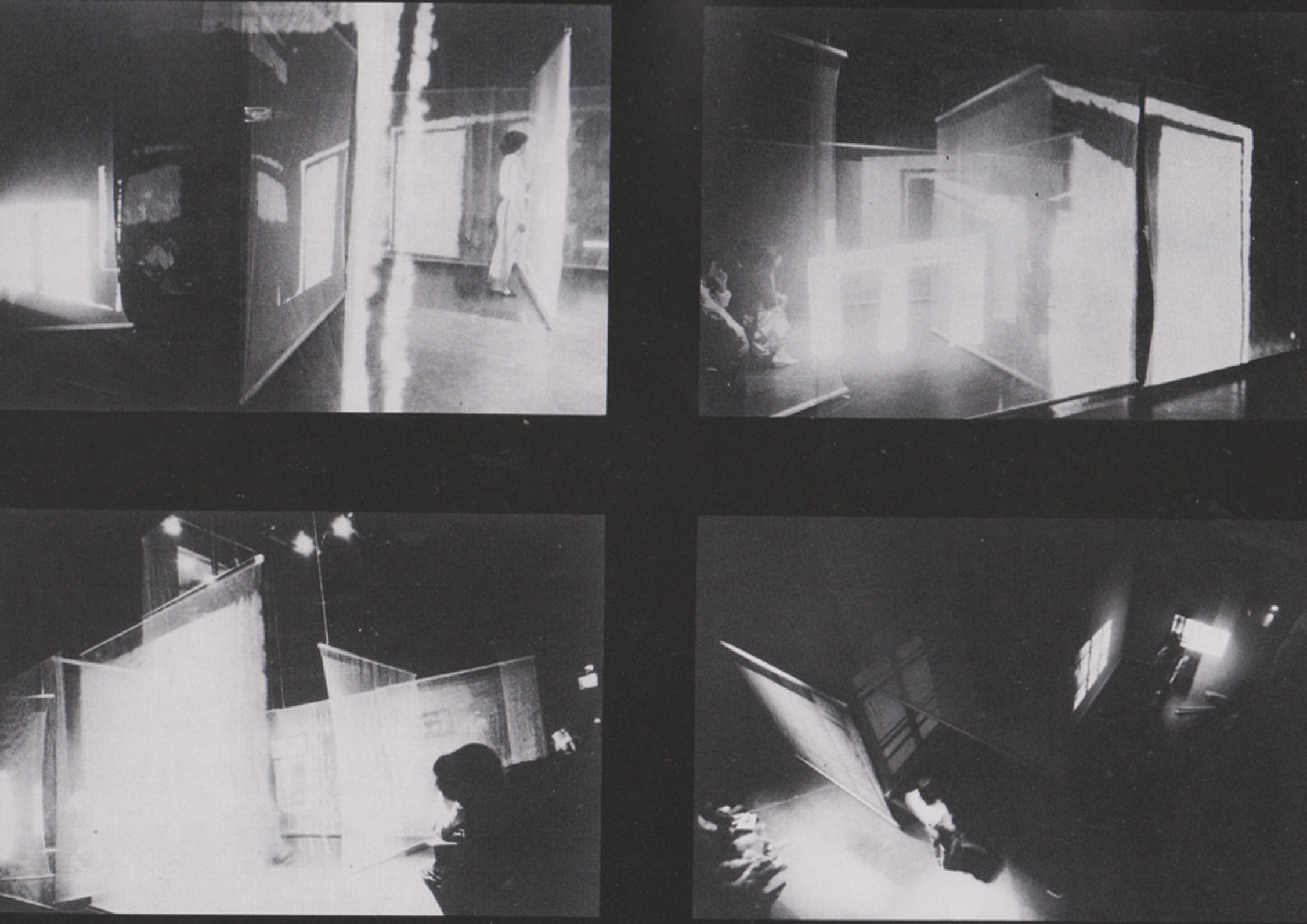

The third and final of these performance events, Object-act-ivities[Figure 6], was originally developed by Choi, with Chiang Afa, 鄭志銳, Kung Chishing, 龔志成, Lau Chingping, 劉清平, Leung Mantao, 梁文道, Leung Pingkwan, 也斯, Mui Cheukyin, 梅卓燕 and Yau Ching, 游靜in the spring of 1989 and, similarly to ASLSP, aimed to investigate the interactive possibilities between various art forms. The objective of the work was to produce an assemblage of words, installation, dance and music, whereby artworks, words and actors would ‘proceed in parallelism, without the need for scripted actions or the director’s effort to unify.’36 That is, with each different element existing as its own discrete strand of action that would encounter, interpenetrate, enliven the others by chance, rather than any one being composed for, or set to the other to form a complementary organic whole. In the wake of the June 4 massacre of 1989, however, such a focus on purely formal concerns overnight became shallow and inadequate. Where ASLSP had employed some degree of structural and thematic signposting, for Object-act-ivitiesall conceptual frameworks were abandoned completely, and the work and its emotional valence was left to unfold in an entirely spontaneous manner. As the actions and gestures emerged improvisationally during the performance, the work became, Choi explains, ‘a perfect receptacle for emotive venting’; a space that allowed for a communal experience of mourning.37 Audience members, milling freely through the Civic Centre and amongst the performers, joined the actions at various points.

For many residents of Hong Kong, the June 4 Massacre had clarified the full implications of the scheduled return of the territory’s sovereignty to mainland China in 1997, precipitating widespread social anxiety. So, while the signing of the Sino-British Joint Declaration on Hong Kong’s future in 1984 may have set the clock for the Handover, it was 1989 that unequivocally determined its mood. Accordingly, many of the gestural actions of Object-act-ivities can be seen to relate to the enactment of oppression and control. The most conspicuous of these is a sequence wherein one performer, Yau Ching, uses strips of white fabric to bind a figure who is wrapped, mummy-like in white, to a wall [Figure 7, 8, 9]. As Yau pins a corner of the white bandage to the wall the bound figure struggles, trying to pull away. The fabric only has so much give, and, reaching the end of its elasticity, the figure is yanked abruptly backwards, their body smacking into the wall over and again. Amplifying this air of claustrophobia is the installation of items of furniture that are in some way deformed or distorted, performative movements that are puppet-like and jagged in nature, and repeated actions of dis- and re-assemblage; interventions into the imaginary of the everyday domestic that allude both to feelings of turbulence, as well as the impending manipulation of Hong Kong’s interior by the distant hands of the Chinese state.38

![]()

![]()

![]() [Figure 7, 8, 9]

Choi Yan Chi, Chiang Afa, Kung Chishing, Lau Chingping, Leung Mantao, Leung Pingkwan, Mui Cheukyin and Yau Ching, Object-act-ivities 東西遊戲 (dung sai jau hei), performance still, 1989. Courtesy of Choi Yan Chi.

[Figure 7, 8, 9]

Choi Yan Chi, Chiang Afa, Kung Chishing, Lau Chingping, Leung Mantao, Leung Pingkwan, Mui Cheukyin and Yau Ching, Object-act-ivities 東西遊戲 (dung sai jau hei), performance still, 1989. Courtesy of Choi Yan Chi.

Despite the formal interest from which the work emerged and the distinct absence of any efforts to cohere the actions of individual performers into a direct or didactic comment on the events of Tian’anmen, Object-act-ivities nevertheless assumed an affective load grounded in the local emotional valence of that historical moment (both personal and collective); absorbing and reflecting timbre of mood and purgation of grief. The ascension of emotion in the work of an artist who had, until this point, been generally disinclined to engage with art’s expressive capacities is unsurprising. The recurrent precepts around which the event and its older siblings had been organised—of autonomy within structure, openness to the living environment, and abstinence from didactic compositional organisation or harmony—naturally attended to and indeed amplified the idiosyncratic gestures of individual performers (and audience members). As well as grief, what emerges, almost incidentally from the work, is a subtle rebuke of the events of June 4 as an attentive intersubjective encounter between people and objects, which protested the banal obedience and unnatural synchronicity that is the prerequisite of all such events of large-scale state sanctioned violence.

It is precisely the indeterminacy of the work that enabled such an eventuation. Object-act-ivities relied on an agonistic, as opposed to consensus based, model of negotiation; elevating plural expression, asynchronicity, and contestation over meaning and action. This horizontal model extended to the relationship of the work with its audience and its environment, where immersive strategies developed by Choi initially within the context of her installation practice assume the viewer as an element generative of the entire environment, rather than as a disinterested subject to be communicated to, or for knowledge to be directed towards. These fundamentally sociable and open-ended structures necessarily leave the work open to elements of chance and contingency, and lead to an action actively constituted by the plural articulations of, and encounters between, its participants, while also being open to the time and space in which it emerged. Within the context of the heavy historic moment in which it was realised, Object-act-ivitiesalmost inevitably absorbed and reflected an endemic atmosphere of fear and bereavement. With its clear presupposition of agency within community, the work might on the one hand be read as a rehearsal for a democracy that was not to come; or on the other, as the active instantiation of a community through a practice of intersubjective/objective curiosity, or even care, even in the face of its foreclosure.

After this period, Choi began to focus more substantially on installation as an expressive practice, turning away from her interest in environmental immersion and spatialisation to begin her Drowned Cycle (1989-97), for which the artist submerged books in water, and later oil within fish tanks. For many artists of Choi’s cohort, Tian’anmen was a sticking point, from which some were able to move on, both in their art practices and in their lives, and others were not.39 From the 1990s onwards, both performance and installation art in Hong Kong can be seen to take something of a ‘local turn’, as artists progressively oriented their addresses to local audiences and concerns.40 In performance this manifested in increasingly prevalent impulses to protest, activism, and community-based interventions focused on the preservation or reclamation of cultural heritage.41 The comparable tendency in installation was an engagement with highly localised aspects of Hong Kong culture including found detritus and local materials; visual/verbal puns of Cantonese language; and the excavation or fabrication of local histories.42 For Choi then, as for Hong Kong in general, the 1980s was a high water mark for a particular kind of performance art, a decade in which this, and other new art forms were largely driven by a deconstructive concern, which subsequent to 1989 and the anxiety that Tian’anmen infused into Hong Kong’s public consciousness was increasingly supplanted by more pressing cultural and political matters, as Hong Kong was forced to reckon with the looming 1997 handover date and the need to shore up a local cultural identity as defence against this process. Beginning with Drowned Cycle, Choi turned in the 1990s to an undercurrent of muted and embalmed grief that coiled through Hong Kong’s domestic spaces in the aftermath of Tian’anmen. It is telling that it was this body of work that was internationally ratified through its inclusion in the First Asia Pacific Triennial (APT) of 1993. The ‘overt funeral symbolism’43 of Drowned Cycle, in which the placement of books in oil or water stands as metaphor for the decomposition of memory and of culture as well as, conversely, their preservation through entombment, is legible as a statement about Hong Kong’s political plight, one which affirmed an existing set of beliefs held by the West about the nature of China and its relationship to its subjects.44The inclusion of Drowned II in the 1993 APT foreshadowed a flare of interest in Hong Kong and its cultural production that was to peak around the handover, wherein an interest in art that could be understood to disclose something of Hong Kong’s intrinsic nature (vis-à-vis it’s political condition) functionally eclipsed these earlier, more opaque and indeterminate forms of cultural expression, relegating artworks that resist coherent narration to a place outside of the story of Hong Kong.

Notes:

About the contributor: Genevieve Trail is a doctoral candidate at the University of Melbourne. Her research is concerned with the development of interdisciplinary performance, video and environmental art in Hong Kong from 1970-1989. She was the recent recipient of the Ursula Hoff Art History Scholarship and Eugenie La Gerche Scholarship, and has been published in journals including Di’van: A Journal of Accounts, Art + Australia, Art Monthly Australasia and Photofile.

Action-based Works, 1986-1989

In the late 1980s, Choi began to develop action-based events, as her efforts to spatialise the painting field became translated into more embodied forms. In 1986, she staged Paintings by Choi Yan Chi and Works of Art in Dialogue with Poetry and Dance, creating artworks in response to the poetry of Leung Ping-kwan 梁秉鈞, which were in turn activated by the dance of Sunny Pang. Two years later, in 1988, she collaborated on As Slow As Possible (慢之極 maan zi gik): An Evening of Music Art Dance [Figure 5]at the invitation of pianist Sabrina Mee Ying Fung 馮美瑩, and with dancers and choreographers Sunny Pang, Willy Tsao, and Yoshiko Waki. The performance’s title is in reference to eponymous piece of music by Fluxus composer John Cage, ASLSP, a work for piano written in 1985, and reworked for the organ in 1987. In Cage’s original composition, the title ASLSP stands for ‘As Slow(ly) and Soft(ly) as Possible’, and aside from this broadly inaugurating instruction, dynamics and tempo are free.30 The event was offered as a tribute to water, a thematic reflected in the installation items which included small plastic bags of water (the kind used to transport fish), a concrete well, and a television continuously screening water related imagery. A block of ice marked time as it melted. Choi also contributed a pile of white gauze, which, in an escalation of her previous use of the material, performers interacted with as a now completely disassembled painterly surface. This clear invocation of Cage’s work decisively indicates Choi’s interest in his aesthetic philosophy, in particular his elevation of environmental and ambient sound and compositional processes of chance and indeterminacy. Cage, was of course, also intrinsic to the development of postmodern dance through his longstanding collaboration with Cunningham. Cage had given a lecture at the SAIC in October of 1977 while Choi was a student there and it is feasible to assume that she attended.31 Unfortunately, due to the paucity of material documenting this period of Choi’s life, the specificities of her intellectual encounters remain, at this stage of research, somewhat speculative. In any case, she would certainly have been exposed to his, as well as other Fluxus theories during her time in Chicago. A far more direct link to Cage’s work emerges through the involvement of avant-garde pianist Sabrina Fung, who, having studied in Vienna and Canada, moved to New York with Andrew Culver in the late 1970s in order to get to know Cage. Culver, who Fung later married, was Cage’s creative assistant for eleven years and visited Hong Kong on a number of occasions.32

Choi and her collaborators were interested in producing a structuring architecture within which performers were free to elaborate idiosyncratic gestures that would exist as generative building blocks comprising the larger event. Although a number of predetermined elements (namely the musical score and the installation that formed the performance environment) tabulated the work, within these parameters a high degree of lateral autonomy was afforded. Individual performers existed as independent and dispersed elements that were nevertheless responding to and encountering each other within a common set of environmental inputs. Such a model respects the integrity of the individual as a discrete entity endowed with agency, but nevertheless understands the individual ultimately as a sociable element whose relational instantiation makes them susceptible to influence and variation in response to an encounter with other elements. Individuals are pliable, maintaining their own boundaries whilst also being open to vision and suggestion as the work progresses. This is a playful model not dissimilar to that of the Fluxus art-game, which ‘gives the rules without the exact details’, instead offering a ‘range of possibilities’ in order to respect both the factor of chance and the agency of actors.33 Choi deliberately selected objects for installation that she felt lent themselves to such activation and play by performers. Crucially, by declining to script relationships between individuals and things, the work remained open to an infinite number of chance interpenetrations and evolutions.34 This duality of structure and improvisation or impromptu-ness alludes to Cage’s practice of constructing ‘freedom within limitations’, as seen in compositions in which the temporal arrangement was pre-set and the content left indeterminate, or vice versa with precise sonic materials provided but their usage left open to interpretation by other actors.35 Choi may also have been influenced by the visual scores of Zuni Icosahedron which, similarly, made use of precise time slots or intervals in order to demarcate different sections of the work. In comparison to Journey to the East, however, in Choi’s performance works objects played a far more significant role, at least equal to that of the performers. Significantly, the process-based and indeterminate nature of such a model necessarily relies on a heightened awareness of fellow participants and their actions. A requisite form of intersubjective attention that works to bind actors in an ecology of feedback, as the progression of the event hinges on each being attuned and open to the gestural propositions of others, and equally, to environmental elements of object and sound that surround them.

[Figure 6] Choi Yan Chi, Chiang Afa, Kung Chishing, Lau Chingping, Leung Mantao, Leung Pingkwan, Mui Cheukyin and Yau Ching, Object-act-ivities 東西遊戲 (dung sai jau hei), performance still, 1989. Courtesy of Choi Yan Chi.

The third and final of these performance events, Object-act-ivities[Figure 6], was originally developed by Choi, with Chiang Afa, 鄭志銳, Kung Chishing, 龔志成, Lau Chingping, 劉清平, Leung Mantao, 梁文道, Leung Pingkwan, 也斯, Mui Cheukyin, 梅卓燕 and Yau Ching, 游靜in the spring of 1989 and, similarly to ASLSP, aimed to investigate the interactive possibilities between various art forms. The objective of the work was to produce an assemblage of words, installation, dance and music, whereby artworks, words and actors would ‘proceed in parallelism, without the need for scripted actions or the director’s effort to unify.’36 That is, with each different element existing as its own discrete strand of action that would encounter, interpenetrate, enliven the others by chance, rather than any one being composed for, or set to the other to form a complementary organic whole. In the wake of the June 4 massacre of 1989, however, such a focus on purely formal concerns overnight became shallow and inadequate. Where ASLSP had employed some degree of structural and thematic signposting, for Object-act-ivitiesall conceptual frameworks were abandoned completely, and the work and its emotional valence was left to unfold in an entirely spontaneous manner. As the actions and gestures emerged improvisationally during the performance, the work became, Choi explains, ‘a perfect receptacle for emotive venting’; a space that allowed for a communal experience of mourning.37 Audience members, milling freely through the Civic Centre and amongst the performers, joined the actions at various points.

For many residents of Hong Kong, the June 4 Massacre had clarified the full implications of the scheduled return of the territory’s sovereignty to mainland China in 1997, precipitating widespread social anxiety. So, while the signing of the Sino-British Joint Declaration on Hong Kong’s future in 1984 may have set the clock for the Handover, it was 1989 that unequivocally determined its mood. Accordingly, many of the gestural actions of Object-act-ivities can be seen to relate to the enactment of oppression and control. The most conspicuous of these is a sequence wherein one performer, Yau Ching, uses strips of white fabric to bind a figure who is wrapped, mummy-like in white, to a wall [Figure 7, 8, 9]. As Yau pins a corner of the white bandage to the wall the bound figure struggles, trying to pull away. The fabric only has so much give, and, reaching the end of its elasticity, the figure is yanked abruptly backwards, their body smacking into the wall over and again. Amplifying this air of claustrophobia is the installation of items of furniture that are in some way deformed or distorted, performative movements that are puppet-like and jagged in nature, and repeated actions of dis- and re-assemblage; interventions into the imaginary of the everyday domestic that allude both to feelings of turbulence, as well as the impending manipulation of Hong Kong’s interior by the distant hands of the Chinese state.38

Despite the formal interest from which the work emerged and the distinct absence of any efforts to cohere the actions of individual performers into a direct or didactic comment on the events of Tian’anmen, Object-act-ivities nevertheless assumed an affective load grounded in the local emotional valence of that historical moment (both personal and collective); absorbing and reflecting timbre of mood and purgation of grief. The ascension of emotion in the work of an artist who had, until this point, been generally disinclined to engage with art’s expressive capacities is unsurprising. The recurrent precepts around which the event and its older siblings had been organised—of autonomy within structure, openness to the living environment, and abstinence from didactic compositional organisation or harmony—naturally attended to and indeed amplified the idiosyncratic gestures of individual performers (and audience members). As well as grief, what emerges, almost incidentally from the work, is a subtle rebuke of the events of June 4 as an attentive intersubjective encounter between people and objects, which protested the banal obedience and unnatural synchronicity that is the prerequisite of all such events of large-scale state sanctioned violence.

It is precisely the indeterminacy of the work that enabled such an eventuation. Object-act-ivities relied on an agonistic, as opposed to consensus based, model of negotiation; elevating plural expression, asynchronicity, and contestation over meaning and action. This horizontal model extended to the relationship of the work with its audience and its environment, where immersive strategies developed by Choi initially within the context of her installation practice assume the viewer as an element generative of the entire environment, rather than as a disinterested subject to be communicated to, or for knowledge to be directed towards. These fundamentally sociable and open-ended structures necessarily leave the work open to elements of chance and contingency, and lead to an action actively constituted by the plural articulations of, and encounters between, its participants, while also being open to the time and space in which it emerged. Within the context of the heavy historic moment in which it was realised, Object-act-ivitiesalmost inevitably absorbed and reflected an endemic atmosphere of fear and bereavement. With its clear presupposition of agency within community, the work might on the one hand be read as a rehearsal for a democracy that was not to come; or on the other, as the active instantiation of a community through a practice of intersubjective/objective curiosity, or even care, even in the face of its foreclosure.

After this period, Choi began to focus more substantially on installation as an expressive practice, turning away from her interest in environmental immersion and spatialisation to begin her Drowned Cycle (1989-97), for which the artist submerged books in water, and later oil within fish tanks. For many artists of Choi’s cohort, Tian’anmen was a sticking point, from which some were able to move on, both in their art practices and in their lives, and others were not.39 From the 1990s onwards, both performance and installation art in Hong Kong can be seen to take something of a ‘local turn’, as artists progressively oriented their addresses to local audiences and concerns.40 In performance this manifested in increasingly prevalent impulses to protest, activism, and community-based interventions focused on the preservation or reclamation of cultural heritage.41 The comparable tendency in installation was an engagement with highly localised aspects of Hong Kong culture including found detritus and local materials; visual/verbal puns of Cantonese language; and the excavation or fabrication of local histories.42 For Choi then, as for Hong Kong in general, the 1980s was a high water mark for a particular kind of performance art, a decade in which this, and other new art forms were largely driven by a deconstructive concern, which subsequent to 1989 and the anxiety that Tian’anmen infused into Hong Kong’s public consciousness was increasingly supplanted by more pressing cultural and political matters, as Hong Kong was forced to reckon with the looming 1997 handover date and the need to shore up a local cultural identity as defence against this process. Beginning with Drowned Cycle, Choi turned in the 1990s to an undercurrent of muted and embalmed grief that coiled through Hong Kong’s domestic spaces in the aftermath of Tian’anmen. It is telling that it was this body of work that was internationally ratified through its inclusion in the First Asia Pacific Triennial (APT) of 1993. The ‘overt funeral symbolism’43 of Drowned Cycle, in which the placement of books in oil or water stands as metaphor for the decomposition of memory and of culture as well as, conversely, their preservation through entombment, is legible as a statement about Hong Kong’s political plight, one which affirmed an existing set of beliefs held by the West about the nature of China and its relationship to its subjects.44The inclusion of Drowned II in the 1993 APT foreshadowed a flare of interest in Hong Kong and its cultural production that was to peak around the handover, wherein an interest in art that could be understood to disclose something of Hong Kong’s intrinsic nature (vis-à-vis it’s political condition) functionally eclipsed these earlier, more opaque and indeterminate forms of cultural expression, relegating artworks that resist coherent narration to a place outside of the story of Hong Kong.

Notes:

- The introspective mood that emerged during this period

at the prospect of imminent reabsorption into mainland China provided a context

around which theoretical frameworks on the territory’s identity could be

clarified, prompting a spate of research and exhibition making by scholars

including Ackbar Abbas, David Clarke and Rey Chow who variously hypothesised

Hong Kong as border(line), transition point, bridge, marginal, liminal, hybrid

and/or disappearing, concepts for which the intellectual landscape of

postcolonialism was generative. For Hong Kong as a culture of ‘disappearance’ see Ackbar M. Abbas, Hong Kong: Culture

and the Politics of Disappearance (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota

Press, 1997); as harmoniously and disjunctively hybrid see David J. Clarke, Hong

Kong Art: Culture and Decolonization (Duke University Press, 2002); and as

a marginal space of productive 'para-sitical intervention' see Rey Chow, Writing

Diaspora: Tactics of Intervention in Contemporary Cultural Studies (Indiana

University Press, 1993), 16.In the context of Hong

Kong, the theory of cultural hybridity must also be read in relation to clear

antecedents in Hong Kong’s familiar discourse of East-meets-West, a construct

that can be dated to at least the early 20th century when it was

frequently employed in contemporaneous descriptions of the Lingnan School, a

school of painting from Canton whose artists were heavily influenced by the

Japanese movement of Nihonga in adopting elements of Western influence. Frank Vigneron, I like Hong Kong: Art and Deterritorialization(Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, 2010), 93.

- Mei Lin Lai, “Lui Shou Kwan & Modern Ink Painting” (Ph.D. Thesis,

Sydney, University of Sydney, 2011), 13–14.

- Abbas, Hong Kong, 7.

- Minglu Gao, “Conceptual Art with Anticonceptual Attitude: Mainland China,

Taiwan, and Hong Kong,” in Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin,

1950s-1980s, ed. László Beke et al. (New York: Queens Museum of

Art, 1999), 130.

- During this period, the only degree program in Fine Arts available in Hong Kong

was offered by the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK). Short courses were

available in the Extra-mural Departments of CUHK, the University of Hong Kong

and Hong Kong Polytechnic (now Hong Kong Polytechnic University).

- Choi Yan

Chi, “Am I Turning Right?,” in [Re-] Fabrication: Choi Yan-Chi’s 30 Years,

Paths of Inter-Disciplinarity in Art, ed. Linda Lai, Exh. Cat., (Hong Kong: Para Site Art Space, 2006), 28.

- The Modern Ink Painting Movement, which by 1975 had come to dominate Hong Kong,

reconfigured Chinese Ink Painting in radical ways, producing new kinds of

stylised abstraction (as seen in the work of Ng Yiu-chung and Cheng Wei-kwok )

and gestural expressionism (as practised by Irene Chou and Lawrence Tam)

- Clarke, Hong Kong Art.

- Linda Lai, “Prologue for Epilogue:

Entrapment, or Rhizomes in the Process of Making,” in [Re-] Fabrication:

Choi Yan-Chi’s 30 Years, Paths of Inter-Disciplinarity in Art, ed. Linda

Lai, Exh. Cat., (Hong Kong: Para Site Art Space, 2006), 44; Mathew Turner,

“Fugitive Pieces,” in [Re-] Fabrication: Choi Yan-Chi’s 30 Years, Paths of

Inter-Disciplinarity in Art, ed. Linda Lai (Hong Kong: Para Site Art Space,

2006), 59.

- Choi Yan Chi, “Am I Turning Right?,” 27.

- Choi Yan

Chi, 27.

- Leung Poshan Anthony, Stories of Hong Kong Artists—Interview

Manuscripts from 1998 (Hong Kong: Art Asia Pacific Holdings, 2019), 254.

- Clarke, Hong Kong Art.

- Linda Lai, ed., [Re-] Fabrication:

Choi Yan-Chi’s 30 Years, Paths of Inter-Disciplinarity in Art, Exh. Cat.,

(Hong Kong, 2006), 153.

- Choi Yan Chi, in Johnson Chang, “A

Painted Space,” in An Extension into Space, Exh. Cat., (Hong Kong: Hong

Kong Arts Centre, 1985), unpaginated.

- An Extension into Space: An Installation

Work by Choi Yan Chi, Exh. Cat., (Hong Kong: Hong Kong Arts Centre, 1985).

- The Chinese script that Choi used within her work of this period was taken from

poetry sent to her by Hon Chi Fun (1922-2019), a key modernist artist in Hong

Kong whom Choi began a relationship with in the 1970s.

- Lai, [Re-] Fabrication, 141.

- Chang, “A Painted Space.”

- Lai, [Re-] Fabrication, 141.

- Choi Yan Chi, “Am I Turning Right?,” 31.

- Choi Yan Chi, 31.

- Choi Yan Chi, in Lai, [Re-]

Fabrication, 192.

- Rossella Ferrari, Transnational Chinese Theatres: Intercultural

Performance Networks in East Asia, Transnational Theatre Histories (Cham:

Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), 75.

- Ferrari, 76.

- Pan Dak Zung 潘德忠 and Ling Gaa Man 凌嘉敏, “A

Theoritical Work about ... «中國旅程» [Journey to the East],” trans.

Valerie Wanling Liu, 學院字花, no. 1 (March 1981): 33.

- Pan Dak Zung 潘德忠 and Ling Gaa Man 凌嘉敏, “A

Theoritical Work about ... «中國旅程» [Journey to the East].”

- Roger Copeland, “Postmodern Dance Postmodern Architecture

Postmodernism,” Performing Arts Journal 7, no. 1 (1983): 31–32.

- Choi Yan Chi, “Hong Kong Contemporary Arts,” Update, University

of Toronto, 96 1995; in, Lai, [Re-] Fabrication, 269.

- John Cage

Trust, “ASLSP,” John Cage Complete Works, accessed March 29, 2021,

https://johncage.org/pp/John-Cage-Work-Detail.cfm?work_ID=30.

- Fluxus artist Joseph Beuys also gave a lecture as part of SAIC’s

Visiting Artist Program in 1974, and installation and site-specific artist

Robert Irwin did so in 1978. It is possible to see the imprint of both of these

artists on Choi’s work.

- Sabrina Fung, e-mail message to author, August 30, 2021.

- Dick Higgins, A Dialectic of Centuries: Towards a Theory

of the New Arts (New York: Printed Editions, 1978), 20–21; quoted in Craig

Saper, “Fluxus as Laboratory,” in The

Fluxus Reader, ed. Ken Friedman (Chicester, West Sussex; New York: Academy