In conversation with Ashley Perry

To cite this contribution:

Eaton, Jeremy and Fliedner, Kelly. Interview with Ashley Perry. ‘Memory Bank 2021’. Currents Journal Issue Two (2021), https://currentsjournal.net/Currents-in-conversation-Ashley-Perry

Download this interview ︎︎︎PDF

Ashley Perry’s course of study:

Master of Fine Arts, Faculty of Fine Arts and Music, Univeristy of Melbourne

Image ^^^ Ashley Perry, We will keep this for you, (2017), looped video.

Jeremy Eaton [JE]: So, to begin, I'm really

interested to hear where you are up to with your research and the arc that your

research has taken over the Masters period?

Ashley Perry [AP]: I started my masters in 2019 and then I took leave last year due to things that occurred pre-COVID. My research project started off broadly looking at the internet, and the intersection of Indigenous experience with post-internet discourse. As I got further into the research, I moved away from that, and I returned to work that I was doing into archives, looking at repatriation and discussions about repatriation. This also considered the practical realisations that came out of that exploration, and so my research this year has been homing in on and focusing on museological approaches to repatriation alongside artistic approaches. I’ve been thinking through these ideas in terms of my own artwork alongside the work of other artists who make works in this area, including Christian Thompson and Julie Gough.

JE: Can you give us some examples of how artistic repatriation functions?

AP: I've been trying to look at a whole bunch of different approaches to it. So, Christian Thompson has a really interesting approach. It includes a spiritual form of repatriation, which is about excising the stories from objects. This may not be exactly how he would talk about it, but I see the excised stories of objects as something that can then be returned to their specific community’s. In a way it potentially separates some of the aura, the Walter Benjamin kind, from the object to actually reclaim the essence of the thing to give back to the community. It acts to heal, but also unpacks what that process might be for the community. Whereas I think Julie Gough has a slightly different approach, in terms of considering the connection to Country, all the locations or histories that an object is from, and what those connections are geographically and politically.

I think my approach to repatriation processes is perhaps a bit more in-line with that kind of approach. This includes criticizing, or engaging with, the processes of histories, stories and methods that have, and could take place. I also work from a position that knows there are limitations to what art can do in this field.

JE: That’s amazing, I think about your material and media approaches to this idea, given you use a lot of technology, which I think it is interesting, especially in the context of thining about memory. I wonder if you could talk about your approach and the methods you use, especially if you're talking about ancestral knowledge and objects, how do these contemporary media forms and approaches to historical objects intersect with each other and your critical perspective?

AP: For some context, I am a Goenpul person from Quandamooka Country, the islands off the southeast coast of Queensland, but I do live on the Countries of the Kulin Nations and so I think this distance from my Country has really informed the way I engage with archives and collections as well. Also, from previous experiences, engaging with collections as an emerging artist, means that it is difficult to generate institutional interest in what I could bring to those spaces. This really made me interested in what the public access and opportunities are. What is an institution actually making available to the public? And not just someone who is a prestigious artist or researcher who can access that material through those privileged access pathways. And so, I think, for me, it was a process of looking at these collections from the outside and asking: Well, what is the public display of these objects? What information is on their website? Or do they have an archive that's accessible? What information is being recorded there? And then working from those relatively accessible vantage points and looking at a whole bunch of different institutions from university collections to National Archives, libraries, museums, even personal websites (blogs), I was able to build my own archive pulled from all these different sources that are related to cultural stories. In particular, I was looking at material from Southeast Queensland, specifically from my Country. Although, an object that was collected in Southeast Queensland was often documented in a particular way that did not specify where that object was from. My process became a way to capture objects from my Mob, but also from other surrounding Countries as well.

This archive I’ve pulled together, then becomes a springboard where I can look through those stories and find things that get reworked into different artworks. So, works like the digital 3D modeling pieces are made by pulling out either stories of objects that don't have documentation of them, or there's maybe a different type of record of a particular object that I can then unpack and remake and some of these stories then turn into sculptural installations.

![]()

![]()

Image ^^^ Ashley Perry, Reformation (2019-21). Steel, monitors, three channel looped video. Exhibited in ‘The Image is not Nothing (Concrete Archives)’, Melbourne's Living Museum of the West.

JE: Considering artistic repatriation and what you’re talking about, and this may be incorrect framing, but I think your practical approach of collating and drawing together narratives and ephemera informs the way you develop forms, and you distil this material into an image from something that had otherwise been dispersed or diffused, and I think that's a really fascinating approach to reclaiming an object.

Kelly Fliedner [KF]: And I find what you were saying about the problems with public access really interesting too. Because as an emerging practitioner you, me or others often struggle to get access to collections that we're interested in. You can, to a degree, leverage your time within the institution to gain access to things that you wouldn't otherwise get access to. But then, once you're in the institution and understand how institutions actually work, you can quickly see that they're often very poorly resourced from within as well, and so that stifles engagement even once you're in. At the University of WA the Berndt Collection is housed, it's one of the largest collections of Indigenous and First Nations anthropological objects anywhere in the world, it's kind of amazing. And yet it's so poorly resourced by the university that there are not sufficient Indigenous practitioners put in place to caretake the actual collection itself. They haven't been able to archive the objects that they have with any kind of cultural specificity and they give any individual object over to someone who is interested in it, and so it's a very frustrating system. But unfortunately, it just takes a lot of resources. Have you experienced that yourself?

AP: Yes, I have two notes on that. I've done a little bit of work with the little North Stradbroke Island Historical Museum, where my family's from and it's always quite interesting. I think working there and seeing the kinds of limited funding that they're working with, for example they have part time roles, by splitting a full-time role, across two people and you know, the struggles that they go through with the limitations that they're working with. And I think from the work that I've done in other institutions as well, you can see there are funding limitations and that impacts their ability to create access or bring people in to work with the objects. And so I don't think it's exclusively the issue of those collections or the institutions themselves, but maybe part of a larger issue. On the other hand I also think institutions perform access too. One experience that was quite formative for me was spending about six months getting in contact with Queensland Museum about accessing their collections and it was always a dead end. You know, responses would stop and then when I arrived at the museum without having access to it, there was this huge display area where they were promoting how accessible their objects and stories are to the community. Like huge banners and posters, and a lot of marketing and promotional resources had gone into performing how accessible their collections are, which is contrary to my experience. But there is also an ‘insider’ form of access too, because a couple weeks later when I was working on other projects a person was like, ‘oh no, I know the curator from there, I'll put you in contact’ and that's how you get in. So, it's quite interesting how the mechanism of that all operates, the informal versus formal, and the performative aspects of these spaces.

JE: Have you had any of these collecting institutions re-encounter your work after you have taken on aspects of their collections, or have you managed to re-enter the institutions with your work in some way?

AP: I haven’t no. A part of a work I have been working on is about submitting objects to institutions to insert them into their collections. But I am yet to get to that part of the process in the project’s life-cycle. These objects I've been working on are compound, small sculptures that have computer components and programming that enacts particular actions within an institution setting. The first one I produced is a surveillance object that takes photos if it's plugged in and archives them to be sent back to a collection to then be reviewed—to give an actual picture of what's inside an institution. The idea was that these could be sent into an institution to help assist with a process of repatriation. I believe you've seen them Jeremy, they are kind of humorous things and I think a lot of the institutions I would like to send them to have collection practices that emphasise historical objects or pieces with a very particular aesthetic. I think the aesthetics of these objects is to challenge that.

![]()

Image ^^^ Ashley Perry, Reconnaissance Object (2019). Epoxy resin, pigment, steel, brass, bronze, Raspberry Pi 3 Model B+, Raspberry Pi Camera Board and wax.

Ashley Perry [AP]: I started my masters in 2019 and then I took leave last year due to things that occurred pre-COVID. My research project started off broadly looking at the internet, and the intersection of Indigenous experience with post-internet discourse. As I got further into the research, I moved away from that, and I returned to work that I was doing into archives, looking at repatriation and discussions about repatriation. This also considered the practical realisations that came out of that exploration, and so my research this year has been homing in on and focusing on museological approaches to repatriation alongside artistic approaches. I’ve been thinking through these ideas in terms of my own artwork alongside the work of other artists who make works in this area, including Christian Thompson and Julie Gough.

JE: Can you give us some examples of how artistic repatriation functions?

AP: I've been trying to look at a whole bunch of different approaches to it. So, Christian Thompson has a really interesting approach. It includes a spiritual form of repatriation, which is about excising the stories from objects. This may not be exactly how he would talk about it, but I see the excised stories of objects as something that can then be returned to their specific community’s. In a way it potentially separates some of the aura, the Walter Benjamin kind, from the object to actually reclaim the essence of the thing to give back to the community. It acts to heal, but also unpacks what that process might be for the community. Whereas I think Julie Gough has a slightly different approach, in terms of considering the connection to Country, all the locations or histories that an object is from, and what those connections are geographically and politically.

I think my approach to repatriation processes is perhaps a bit more in-line with that kind of approach. This includes criticizing, or engaging with, the processes of histories, stories and methods that have, and could take place. I also work from a position that knows there are limitations to what art can do in this field.

JE: That’s amazing, I think about your material and media approaches to this idea, given you use a lot of technology, which I think it is interesting, especially in the context of thining about memory. I wonder if you could talk about your approach and the methods you use, especially if you're talking about ancestral knowledge and objects, how do these contemporary media forms and approaches to historical objects intersect with each other and your critical perspective?

AP: For some context, I am a Goenpul person from Quandamooka Country, the islands off the southeast coast of Queensland, but I do live on the Countries of the Kulin Nations and so I think this distance from my Country has really informed the way I engage with archives and collections as well. Also, from previous experiences, engaging with collections as an emerging artist, means that it is difficult to generate institutional interest in what I could bring to those spaces. This really made me interested in what the public access and opportunities are. What is an institution actually making available to the public? And not just someone who is a prestigious artist or researcher who can access that material through those privileged access pathways. And so, I think, for me, it was a process of looking at these collections from the outside and asking: Well, what is the public display of these objects? What information is on their website? Or do they have an archive that's accessible? What information is being recorded there? And then working from those relatively accessible vantage points and looking at a whole bunch of different institutions from university collections to National Archives, libraries, museums, even personal websites (blogs), I was able to build my own archive pulled from all these different sources that are related to cultural stories. In particular, I was looking at material from Southeast Queensland, specifically from my Country. Although, an object that was collected in Southeast Queensland was often documented in a particular way that did not specify where that object was from. My process became a way to capture objects from my Mob, but also from other surrounding Countries as well.

This archive I’ve pulled together, then becomes a springboard where I can look through those stories and find things that get reworked into different artworks. So, works like the digital 3D modeling pieces are made by pulling out either stories of objects that don't have documentation of them, or there's maybe a different type of record of a particular object that I can then unpack and remake and some of these stories then turn into sculptural installations.

Image ^^^ Ashley Perry, Reformation (2019-21). Steel, monitors, three channel looped video. Exhibited in ‘The Image is not Nothing (Concrete Archives)’, Melbourne's Living Museum of the West.

JE: Considering artistic repatriation and what you’re talking about, and this may be incorrect framing, but I think your practical approach of collating and drawing together narratives and ephemera informs the way you develop forms, and you distil this material into an image from something that had otherwise been dispersed or diffused, and I think that's a really fascinating approach to reclaiming an object.

Kelly Fliedner [KF]: And I find what you were saying about the problems with public access really interesting too. Because as an emerging practitioner you, me or others often struggle to get access to collections that we're interested in. You can, to a degree, leverage your time within the institution to gain access to things that you wouldn't otherwise get access to. But then, once you're in the institution and understand how institutions actually work, you can quickly see that they're often very poorly resourced from within as well, and so that stifles engagement even once you're in. At the University of WA the Berndt Collection is housed, it's one of the largest collections of Indigenous and First Nations anthropological objects anywhere in the world, it's kind of amazing. And yet it's so poorly resourced by the university that there are not sufficient Indigenous practitioners put in place to caretake the actual collection itself. They haven't been able to archive the objects that they have with any kind of cultural specificity and they give any individual object over to someone who is interested in it, and so it's a very frustrating system. But unfortunately, it just takes a lot of resources. Have you experienced that yourself?

AP: Yes, I have two notes on that. I've done a little bit of work with the little North Stradbroke Island Historical Museum, where my family's from and it's always quite interesting. I think working there and seeing the kinds of limited funding that they're working with, for example they have part time roles, by splitting a full-time role, across two people and you know, the struggles that they go through with the limitations that they're working with. And I think from the work that I've done in other institutions as well, you can see there are funding limitations and that impacts their ability to create access or bring people in to work with the objects. And so I don't think it's exclusively the issue of those collections or the institutions themselves, but maybe part of a larger issue. On the other hand I also think institutions perform access too. One experience that was quite formative for me was spending about six months getting in contact with Queensland Museum about accessing their collections and it was always a dead end. You know, responses would stop and then when I arrived at the museum without having access to it, there was this huge display area where they were promoting how accessible their objects and stories are to the community. Like huge banners and posters, and a lot of marketing and promotional resources had gone into performing how accessible their collections are, which is contrary to my experience. But there is also an ‘insider’ form of access too, because a couple weeks later when I was working on other projects a person was like, ‘oh no, I know the curator from there, I'll put you in contact’ and that's how you get in. So, it's quite interesting how the mechanism of that all operates, the informal versus formal, and the performative aspects of these spaces.

JE: Have you had any of these collecting institutions re-encounter your work after you have taken on aspects of their collections, or have you managed to re-enter the institutions with your work in some way?

AP: I haven’t no. A part of a work I have been working on is about submitting objects to institutions to insert them into their collections. But I am yet to get to that part of the process in the project’s life-cycle. These objects I've been working on are compound, small sculptures that have computer components and programming that enacts particular actions within an institution setting. The first one I produced is a surveillance object that takes photos if it's plugged in and archives them to be sent back to a collection to then be reviewed—to give an actual picture of what's inside an institution. The idea was that these could be sent into an institution to help assist with a process of repatriation. I believe you've seen them Jeremy, they are kind of humorous things and I think a lot of the institutions I would like to send them to have collection practices that emphasise historical objects or pieces with a very particular aesthetic. I think the aesthetics of these objects is to challenge that.

Image ^^^ Ashley Perry, Reconnaissance Object (2019). Epoxy resin, pigment, steel, brass, bronze, Raspberry Pi 3 Model B+, Raspberry Pi Camera Board and wax.

JE: It is interesting to think about this appeal to the institution and the

broader way you’re navigating that space, different collections and

histories, whilst maintaining these different approaches simultaneously, and it raises

a question of who the potential audience for this work is, and how do you envisage their own memories and experiences inflecting their encounter with

your work?

AP: I think my works operate in a few different ways. When people from my community encounter one of the installations that might have parts that specifically relate to my Mob or the Country that I’m from, many of the members of my community are quite familiar with the references to cultural practices. They will have a particular relationship to the work. At the same time there's a lot of different experiences that people could have with the work as well. They connect with other parts of history and other communities, especially their relationship to institutional collections, ideas of historical framing and repatriation as well. I think there's a number of different ways that people can connect to and experience my work, and I think I'm quite open for how that can shift for different people. In terms of the objecs I was just talking about, a lot of people connect them to the idea of surveillance for instance, or an uncomfortable feeling of being watched.

JE: I recently worked with Léuli [Eshrāghi] and ia has this idea that I’m really drawn to that looks at ancestral knowledge and memory as a type of futurity. I find that sense of temporal movement and process really engaging and I think about some of your technological approaches as an interface for how different people and your Mob could encounter your work and ancestral knowledges — it produces this interesting confluence of different temporal registers all occurring at once.

AP: That is interesting because I've always been critical of the way people say that Indigenous culture is a living culture but then under the umbrella of this idea, they don’t include things from a broader cultural consciousness. You know, when you walk into a museum and there's a lot of material culture, and you see what you expect to see, particular types of cultural practices, but you don't see the law books of the first Indigenous lawyers for example. I think by questioning how we frame culture that we can start to slowly think through what could be included in these collections. Maybe it is something like tech or other media that can create these relationships to culture and different practices, which creates unexpected and potentially new connections. That’s not to say that there isn’t value in the stories in the archive, we can still learn from what is there and take this knowledge with us into the future

KF: I think that that idea of futurity is really interesting, not only for thinking about ways Indigenous people or groups might work with an archive, question an archive or work to undermine it, but create a shift in its processes. It's a really useful way of thinking about archives, because when you think about an archive or even submitting your thesis, right, you have written the paper to capture a group of works that have been made now. You're tethering it to a historical marker which is 2021 and then all of the context of 2021 gets scooped up with it, or it becomes a memorial for this moment. But contemporary artistic practice is not really like that it's always constantly moving and shifting and changing, and so what do you do with the information that has been tacked onto that signpost of history?

AP: I was at a talk four days ago about submitting a thesis and I was thinking during the meeting what if I have an amendment after? I was like, can I go back into the archived thesis and make some amendments?

KF: But the point is, you can't do that. Wouldn't it be really great if you could?

AP: Yes, within other fields of the university, there is the idea of, you know, continuing to publish. And you become like a researcher in the university and you’re endlessly publishing papers. Then, maybe one of those papers four years down the line articulates an amendment to your thesis, by incorporating new research that's come out. But in contrast, it is a problem with how art schools work, where there is not space for you to become a researcher in that same way and to update your record through research processes. But I like the idea of being able to change or adapt the archive.

JE: With all of that in mind, and thinking about institutions, now that you've gone through this process of research and developed some of your practical outcomes and writing it will fall into that expansive archive of the institution, how do you see it managing to maintain a critical position, which I think your work is about, especially when we talk about institutional access and repatriation. How do you see your project holding that position within the archive of the university?

AP: I don’t think my project specifically looked at its own complicity with the archive of the university, research and those specific systems, which might be a bit of an oversight. But I think in terms of the areas that I have been looking at that I am hopefully offering something new to the pool of practitioners who are also working in this field.

KF: I really see what you mean. And also, from the perspective of my own research, I’m simultaneously having problems not just with archives, but also the commercialization of the uni sector and the fact that casual employees don't have rights and so it's a labour law issue. There are these multiple things that we tend to have very strong opinions about yet we continue to work within this structure, and so I feel like I reconcile these things by taking pleasure in researching and spending time with the thing that I have chosen to sit with. It's a of way of respecting the content in that pleasure can be found in it and that’s how I reconcile my time, if that makes sense…

AP: Definitely. I think it's such a big grey area. I’ve written a section about the history of institutions and museum collections as a way to contextualize how I got to my practice and have done some uncovering—in-line with what we were talking about earlier—around the maintenance of collections and accessibility. For example, I read an article that's about a museum collection from the 1500s in Italy and they're talking about how their labelling system collapsed because it wasn't really maintained for 100 years, and all of the specimens in the whole collection were mixed-up because there weren’t the resources even back then to maintain collections. And these issues have been ongoing for hundreds of years across a number of different countries and cultures. Then at the same time, looking at the National Archives in Australia, which is struggling with the same kind of issue of not being able to document or digitize all of their photographs in time before they actually expire. Then there’s this weird situation where we as employees of these spaces, want the best for the collections, but how do you manage that? When you have your own bills and maybe you are only funded to spend a half day on a project, if you are lucky.

![]()

![]()

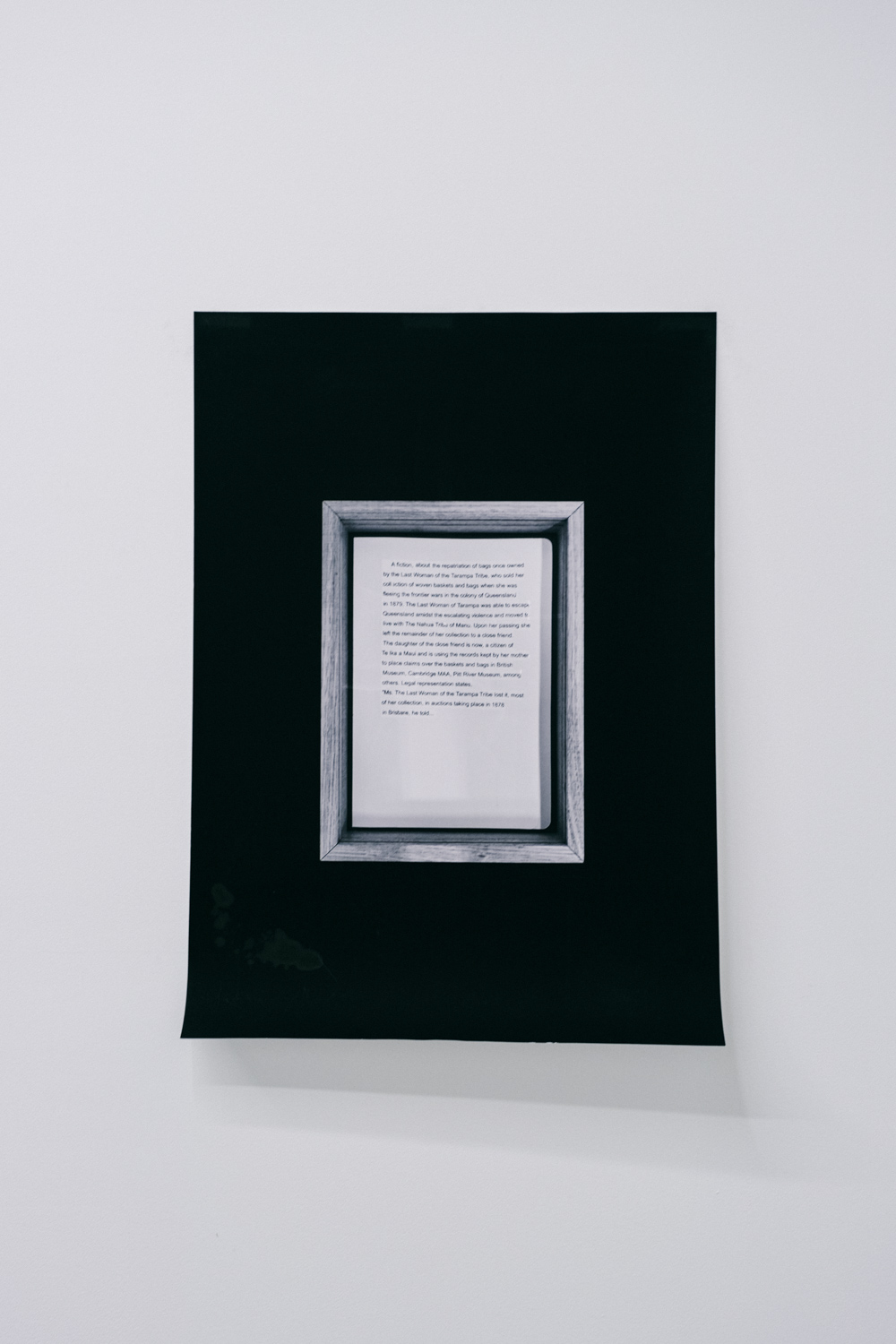

Image ^^^ Ashley Perry, enlighten illumination (2020). Sandblasted acrylic, aluminum, and LED strip and A Fiction, about the repatriation of...(2017).Poster. Both exhibited in ‘An Incomplete Register’, Outer Space. Documentation: Charlie Hillhouse.

JE: Yes, it is a similar situation with digital attrition and a lot of conservation, trying to deal with video art and digital technology now, institutions can't keep up fast enough.

KF: Not to mention the question of what is best practice in this space? Do we have to digitize everything? UWA is a part of this huge university consortium in WA, and so a bunch of universities got together, and they're like ‘we're going to digitize everything.’ And yet they are also aiming to reduce their footprint to something along the lines of negative emissions by 2050, and actually, if you have a million TB capacity, to host your archives, then actually the sheer footprint of that is enormous. And so the assumptions that digitization is even the thing that we need to do is interesting to me.

AP: Definitely, in terms of these huge server rooms and the amount of energy that they use really begs the question are the things you're digitizing even worth keeping? Are some things fine to be lost to history?

KF: Do I need to see James Stirling actively colonizing? Why can’t we just let some things gather dust.

AP: Exactly. In the discussion around conservation and obsolescence, I have works that I’ve produced over the last ten to eight years and so much has changed in that period of time in terms of new technology, file types not being supported anymore or outmoded software updates. It becomes really tricky to navigate. Some artists go to the trouble of seeking out something from a particular period of time, to be able to continue producing works with anachronistic tech, but I think for me I've been interested in going with the flow of how things have changed, and reworking things when I can. I guess that artworks from these particular times become like a stamp, or like we were talking about earlier that it captures everything from a particular moment.

JE: Speaking of time, what do you think is next?

AP: My research project really has uncovered a number of areas I would like to continue exploring. I like the idea of understanding what you may be pushing against, and it makes me think that there's a lot of work to be done in the histories around cultural objects. It is something I'll keep working on. I’m also intrigued by the histories of museum collections as a larger construct and ideology. There are some things that I uncovered through the research in the last year around how we got to this point of having art gallery's and anthropological collections separated, and when that started to emerge is an interesting period of time. It is absurd that a lot of museums don’t reflect on their own history, and I think it is interesting to try and understand those histories a little more deeply to unpack why we are at the point that we are at. And perhaps there is something in that, that can impact some of the issues that are happening now with cultural objects.

About Ashley Perry:

Ashley Perry is an interdisciplinary Goenpul artist from Quandamooka country. His recent works come from research into Quandamooka cultural practices, focusing on material culture held in museum, university, and private collections. Perry’s research is used to produce works that uncover and question the discrepancies embedded in these archives. Drawing on firsthand accounts to historical documents, these varied and often differing accounts are interrogated, compared, and are used to produce sculptures, installations, videos and digital renderings. Perry’s works enter a dialogue, questioning the certainty around institutional and narrated accounts, engaging in a process of speculative potential. His recent works have examined information and data systems, interrogating the methods of collecting and categorising. Perry’s works often examine the legacy of colonialism in these systems as way of understanding embedded issues in their current form. Perry was the recipient of the Incinerator Art Award: Art for Social Change (2019). He recently presented work in Florence, Italy for the First Commissions Project, the University of Melbourne.

AP: I think my works operate in a few different ways. When people from my community encounter one of the installations that might have parts that specifically relate to my Mob or the Country that I’m from, many of the members of my community are quite familiar with the references to cultural practices. They will have a particular relationship to the work. At the same time there's a lot of different experiences that people could have with the work as well. They connect with other parts of history and other communities, especially their relationship to institutional collections, ideas of historical framing and repatriation as well. I think there's a number of different ways that people can connect to and experience my work, and I think I'm quite open for how that can shift for different people. In terms of the objecs I was just talking about, a lot of people connect them to the idea of surveillance for instance, or an uncomfortable feeling of being watched.

JE: I recently worked with Léuli [Eshrāghi] and ia has this idea that I’m really drawn to that looks at ancestral knowledge and memory as a type of futurity. I find that sense of temporal movement and process really engaging and I think about some of your technological approaches as an interface for how different people and your Mob could encounter your work and ancestral knowledges — it produces this interesting confluence of different temporal registers all occurring at once.

AP: That is interesting because I've always been critical of the way people say that Indigenous culture is a living culture but then under the umbrella of this idea, they don’t include things from a broader cultural consciousness. You know, when you walk into a museum and there's a lot of material culture, and you see what you expect to see, particular types of cultural practices, but you don't see the law books of the first Indigenous lawyers for example. I think by questioning how we frame culture that we can start to slowly think through what could be included in these collections. Maybe it is something like tech or other media that can create these relationships to culture and different practices, which creates unexpected and potentially new connections. That’s not to say that there isn’t value in the stories in the archive, we can still learn from what is there and take this knowledge with us into the future

KF: I think that that idea of futurity is really interesting, not only for thinking about ways Indigenous people or groups might work with an archive, question an archive or work to undermine it, but create a shift in its processes. It's a really useful way of thinking about archives, because when you think about an archive or even submitting your thesis, right, you have written the paper to capture a group of works that have been made now. You're tethering it to a historical marker which is 2021 and then all of the context of 2021 gets scooped up with it, or it becomes a memorial for this moment. But contemporary artistic practice is not really like that it's always constantly moving and shifting and changing, and so what do you do with the information that has been tacked onto that signpost of history?

AP: I was at a talk four days ago about submitting a thesis and I was thinking during the meeting what if I have an amendment after? I was like, can I go back into the archived thesis and make some amendments?

KF: But the point is, you can't do that. Wouldn't it be really great if you could?

AP: Yes, within other fields of the university, there is the idea of, you know, continuing to publish. And you become like a researcher in the university and you’re endlessly publishing papers. Then, maybe one of those papers four years down the line articulates an amendment to your thesis, by incorporating new research that's come out. But in contrast, it is a problem with how art schools work, where there is not space for you to become a researcher in that same way and to update your record through research processes. But I like the idea of being able to change or adapt the archive.

JE: With all of that in mind, and thinking about institutions, now that you've gone through this process of research and developed some of your practical outcomes and writing it will fall into that expansive archive of the institution, how do you see it managing to maintain a critical position, which I think your work is about, especially when we talk about institutional access and repatriation. How do you see your project holding that position within the archive of the university?

AP: I don’t think my project specifically looked at its own complicity with the archive of the university, research and those specific systems, which might be a bit of an oversight. But I think in terms of the areas that I have been looking at that I am hopefully offering something new to the pool of practitioners who are also working in this field.

KF: I really see what you mean. And also, from the perspective of my own research, I’m simultaneously having problems not just with archives, but also the commercialization of the uni sector and the fact that casual employees don't have rights and so it's a labour law issue. There are these multiple things that we tend to have very strong opinions about yet we continue to work within this structure, and so I feel like I reconcile these things by taking pleasure in researching and spending time with the thing that I have chosen to sit with. It's a of way of respecting the content in that pleasure can be found in it and that’s how I reconcile my time, if that makes sense…

AP: Definitely. I think it's such a big grey area. I’ve written a section about the history of institutions and museum collections as a way to contextualize how I got to my practice and have done some uncovering—in-line with what we were talking about earlier—around the maintenance of collections and accessibility. For example, I read an article that's about a museum collection from the 1500s in Italy and they're talking about how their labelling system collapsed because it wasn't really maintained for 100 years, and all of the specimens in the whole collection were mixed-up because there weren’t the resources even back then to maintain collections. And these issues have been ongoing for hundreds of years across a number of different countries and cultures. Then at the same time, looking at the National Archives in Australia, which is struggling with the same kind of issue of not being able to document or digitize all of their photographs in time before they actually expire. Then there’s this weird situation where we as employees of these spaces, want the best for the collections, but how do you manage that? When you have your own bills and maybe you are only funded to spend a half day on a project, if you are lucky.

Image ^^^ Ashley Perry, enlighten illumination (2020). Sandblasted acrylic, aluminum, and LED strip and A Fiction, about the repatriation of...(2017).Poster. Both exhibited in ‘An Incomplete Register’, Outer Space. Documentation: Charlie Hillhouse.

JE: Yes, it is a similar situation with digital attrition and a lot of conservation, trying to deal with video art and digital technology now, institutions can't keep up fast enough.

KF: Not to mention the question of what is best practice in this space? Do we have to digitize everything? UWA is a part of this huge university consortium in WA, and so a bunch of universities got together, and they're like ‘we're going to digitize everything.’ And yet they are also aiming to reduce their footprint to something along the lines of negative emissions by 2050, and actually, if you have a million TB capacity, to host your archives, then actually the sheer footprint of that is enormous. And so the assumptions that digitization is even the thing that we need to do is interesting to me.

AP: Definitely, in terms of these huge server rooms and the amount of energy that they use really begs the question are the things you're digitizing even worth keeping? Are some things fine to be lost to history?

KF: Do I need to see James Stirling actively colonizing? Why can’t we just let some things gather dust.

AP: Exactly. In the discussion around conservation and obsolescence, I have works that I’ve produced over the last ten to eight years and so much has changed in that period of time in terms of new technology, file types not being supported anymore or outmoded software updates. It becomes really tricky to navigate. Some artists go to the trouble of seeking out something from a particular period of time, to be able to continue producing works with anachronistic tech, but I think for me I've been interested in going with the flow of how things have changed, and reworking things when I can. I guess that artworks from these particular times become like a stamp, or like we were talking about earlier that it captures everything from a particular moment.

JE: Speaking of time, what do you think is next?

AP: My research project really has uncovered a number of areas I would like to continue exploring. I like the idea of understanding what you may be pushing against, and it makes me think that there's a lot of work to be done in the histories around cultural objects. It is something I'll keep working on. I’m also intrigued by the histories of museum collections as a larger construct and ideology. There are some things that I uncovered through the research in the last year around how we got to this point of having art gallery's and anthropological collections separated, and when that started to emerge is an interesting period of time. It is absurd that a lot of museums don’t reflect on their own history, and I think it is interesting to try and understand those histories a little more deeply to unpack why we are at the point that we are at. And perhaps there is something in that, that can impact some of the issues that are happening now with cultural objects.

About Ashley Perry:

Ashley Perry is an interdisciplinary Goenpul artist from Quandamooka country. His recent works come from research into Quandamooka cultural practices, focusing on material culture held in museum, university, and private collections. Perry’s research is used to produce works that uncover and question the discrepancies embedded in these archives. Drawing on firsthand accounts to historical documents, these varied and often differing accounts are interrogated, compared, and are used to produce sculptures, installations, videos and digital renderings. Perry’s works enter a dialogue, questioning the certainty around institutional and narrated accounts, engaging in a process of speculative potential. His recent works have examined information and data systems, interrogating the methods of collecting and categorising. Perry’s works often examine the legacy of colonialism in these systems as way of understanding embedded issues in their current form. Perry was the recipient of the Incinerator Art Award: Art for Social Change (2019). He recently presented work in Florence, Italy for the First Commissions Project, the University of Melbourne.

Currents is a collaboration between the Centre of Visual Art (CoVA) at the University of Melbourne and the School of Design, University of Western Australia, and is funded through the Schenberg International Arts Collaboration Program. The Advisory Board and Editorial Committee are comprised of staff and graduate students from across the University of Melbourne and the University of Western Australia.

Currents acknowledges the traditional owners and ongoing custodians of the land on which this journal is produced—the Boonwurung and Wurundjeri people of the Eastern Kulin Nation and Whadjuk people. We pay our respects to land, ancestors and Elders, and know that education involves working with their guidance to improve the lives of all.

ISSN 2652-8207

![]()

![]()

Currents acknowledges the traditional owners and ongoing custodians of the land on which this journal is produced—the Boonwurung and Wurundjeri people of the Eastern Kulin Nation and Whadjuk people. We pay our respects to land, ancestors and Elders, and know that education involves working with their guidance to improve the lives of all.

ISSN 2652-8207