Issue One 2020

In Issue One,

Alex Hedt critically analyses the performative incorporation of Auslan

interpretation in Queen Kong Episode II: Queen Kong in Outer Space;

Paul Boyé brings together an analysis of Jean-François Lyotard’s seminal The

Postmodern Condition text and his exhibition project Les

Immatériaux: Art, Science, and Theory, moving toward an understanding of

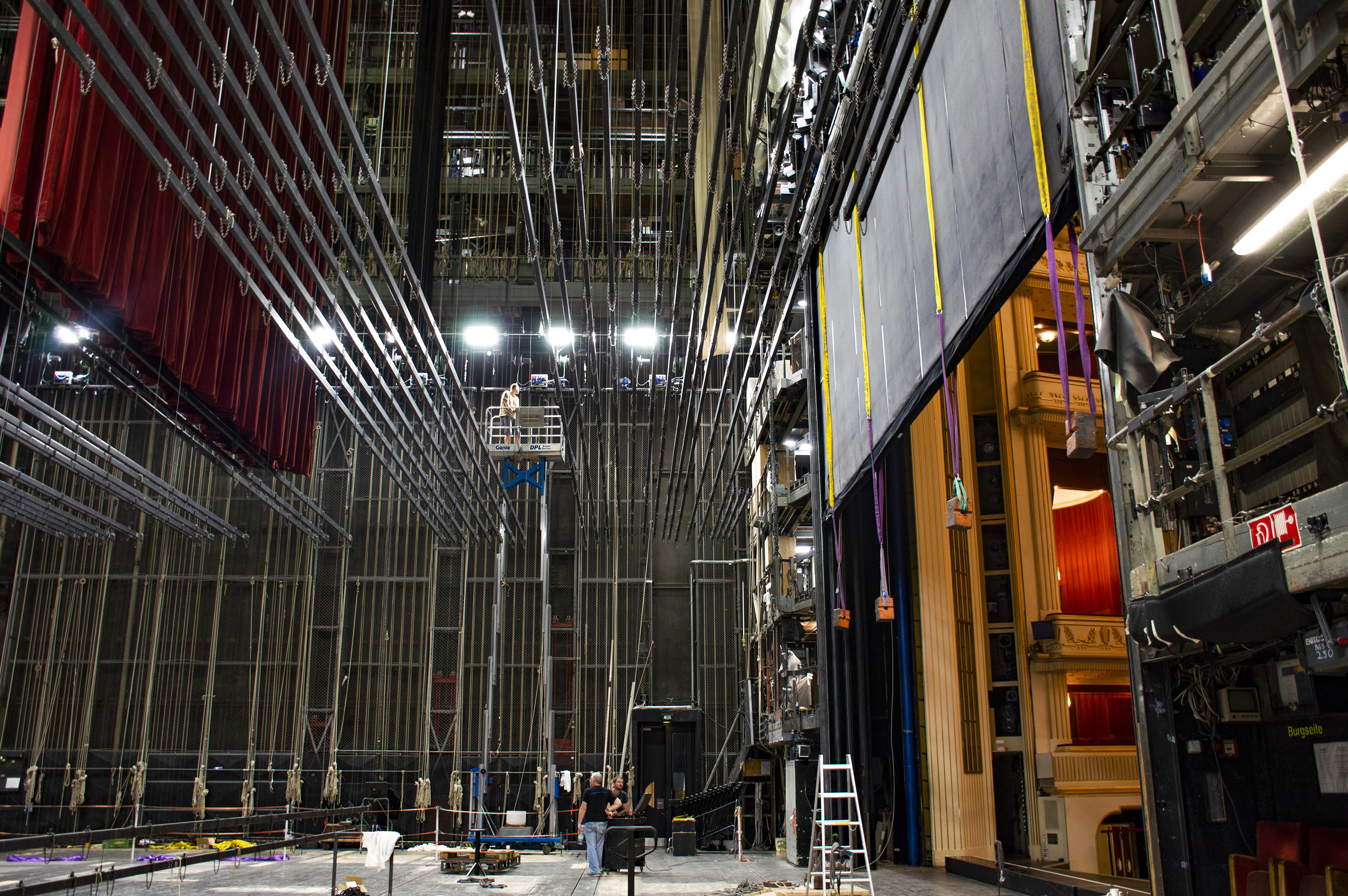

contemporary posthuman theory; Madeline Taylor discusses the delineated

cultures of belonging between technical and creative teams in theatre

production; Elizabeth Smith explores how contemporary institutions are

collecting, archiving and interpreting the work of German modernist

photographer August Sander; and, Chelsea Coon discusses the endurance

performance framework of her performances all star and Phases to

explore the interrelated roles of space, time and the body as she enacts a

series of excessive acts.

Together they represent the broad and interdisciplinary research practices—including theatre, film, visual art, art history and theory—of postgraduate study from the Faculty of Fine Arts and Music, University of Melbourne and the School of Design, University of Western Australia.

Together they represent the broad and interdisciplinary research practices—including theatre, film, visual art, art history and theory—of postgraduate study from the Faculty of Fine Arts and Music, University of Melbourne and the School of Design, University of Western Australia.

Contents

- Introduction — Jeremy Eaton and Kelly Fliedner

- Access and Aesthetics: Cultural Considerations in Interpreting Music and Theatre for Australia's d/Deaf Community — Alex Hedt

- The Inhuman Condition: Jean-François Lyotard’s curatorial experiments with the technological sublime — Paul Boyé

- Belonging Backstage: “Us” and “Them” in Production — Madeline Taylor

- Catching Archive Fever: Delving Into August Sander’s Archive — Elizabeth Smith

- Space, Time, and Excessive Performances of Endurance — Chelsea Coon

Naarm/Melbourne and Boorloo/Perth

are cities by the ocean, port cities whose residents share a nationality, but

whose geographies are distant. We are connected by land just as we are

connected by ocean; from Doogalup/Cape Leeuwin to Mendi-Moke/Flinders through

southern waters that route and re-route our pathways of possibility, which

suggests we might come to rest in places known and unknown.

Currents takes its title from such a sensibility, from the desire to reach out, to connect; to make sense of the spaces between tides and time, between institutions of learning, states and cities that represent and are representative; between orientations of Pacific and Indian, American and Asian. It comes from a saltwater consciousness, a port awareness, a belief in continents that are more than nations; all as a way to share in research and development—to share thoughts and art.

Hosted between the University of Melbourne and the University of Western Australia, Currents was initiated in 2019 with these sentiments in mind, as an interdisciplinary journal that encompasses art, theatre, dance and music history, theoretical developments, and contemporary cultural practice arising from each of the geographically distant institutions. This was before the prevalence of the pandemic and the ensuing year of lockdowns and the eclipse of our work and education processes by the digital.

As this year advanced, Currents continued to develop in a context whereby our local, national and international movements were limited, and changes to the forms and processes of higher education were implemented. And while we all experienced these unprecedented physical and social restrictions, from an education, research and arts perspective, 2020 could be characterised by a kind of agility, as everyone has repeatedly ‘pivoted’ in response to the ever shifting government edicts dictated by the circumstances of the pandemic.

Currents takes its title from such a sensibility, from the desire to reach out, to connect; to make sense of the spaces between tides and time, between institutions of learning, states and cities that represent and are representative; between orientations of Pacific and Indian, American and Asian. It comes from a saltwater consciousness, a port awareness, a belief in continents that are more than nations; all as a way to share in research and development—to share thoughts and art.

Hosted between the University of Melbourne and the University of Western Australia, Currents was initiated in 2019 with these sentiments in mind, as an interdisciplinary journal that encompasses art, theatre, dance and music history, theoretical developments, and contemporary cultural practice arising from each of the geographically distant institutions. This was before the prevalence of the pandemic and the ensuing year of lockdowns and the eclipse of our work and education processes by the digital.

As this year advanced, Currents continued to develop in a context whereby our local, national and international movements were limited, and changes to the forms and processes of higher education were implemented. And while we all experienced these unprecedented physical and social restrictions, from an education, research and arts perspective, 2020 could be characterised by a kind of agility, as everyone has repeatedly ‘pivoted’ in response to the ever shifting government edicts dictated by the circumstances of the pandemic.

It is from within this context

that Currents has emerged. By necessity and by design, Currents has

come to embody elements of the agility and responsiveness required of us in

2020. We have negotiated and renegotiated the shifting circumstances of

research and the opportunities afforded by digital publication. As the title Currents suggests, the journal has become defined by a type of movement and

responsiveness, from the peer-review process, collaborative exchanges,

editorial processes to the style of its serial publication.

Furthermore, this period has necessitated a change in how we work as well as why. There is certainly more online activity, from classes to seminars to journals like ours. And so, it seems important to consider how we connect across and within and through digital divides, platforms, possibilities—all as a way to think about a new reality, a moment in need of articulation and consideration. We situate our work in light of this, thinking, too, of how we might begin to practice our craft as postgraduate scholars.

As a research journal, Currents was initially established with a relatively conservative understanding of peer-review, which derives from the sciences. We were following a process whereby each paper was anonymously reviewed by two experts in the field against a prescriptive set of criteria. What we found was that the interdisciplinary nature of Currents and the unique research styles and methodologies of each contribution did not necessarily benefit from this traditional approach to review and feedback. While articles methodologically defined by an ethnographic approach to research benefitted from structured reviews, other papers that took a subjective and exegetical route through creative practice benefited from reviews responding to specific prompts that elaborated on aspects of the author’s research.

Furthermore, this period has necessitated a change in how we work as well as why. There is certainly more online activity, from classes to seminars to journals like ours. And so, it seems important to consider how we connect across and within and through digital divides, platforms, possibilities—all as a way to think about a new reality, a moment in need of articulation and consideration. We situate our work in light of this, thinking, too, of how we might begin to practice our craft as postgraduate scholars.

As a research journal, Currents was initially established with a relatively conservative understanding of peer-review, which derives from the sciences. We were following a process whereby each paper was anonymously reviewed by two experts in the field against a prescriptive set of criteria. What we found was that the interdisciplinary nature of Currents and the unique research styles and methodologies of each contribution did not necessarily benefit from this traditional approach to review and feedback. While articles methodologically defined by an ethnographic approach to research benefitted from structured reviews, other papers that took a subjective and exegetical route through creative practice benefited from reviews responding to specific prompts that elaborated on aspects of the author’s research.

This flexible approach to different styles of research in conjunction

with mentoring and collaborative editorial approaches, has assisted authors—all

of whom are at various stages in their research degrees—to sharpen and deepen

aspects of their field of interest. As editors, we have become comfortable with

this experimental and more collaborative approach to peer-review, and we

anticipate that this will develop further as we receive more experimental

submissions in the form of creative works, music scores, scripts or the like.

Indicative of the interdisciplinarity of Currents, the first issue includes papers from students in visual art, art history, production, theatre studies and film. It takes to task various critical and social understandings of each of these discrete disciplines. Working through these exciting and various takes on the topics has allowed us to gain feedback from researchers who may be from laterally related fields, providing valuable and, at times, unusual insights into each of the papers.

Issue One, in a broad sense, seems to be characterised by questions that surround performance and institutional structures. There is an analysis of the workplace politics implicit in theatre from Madeline Taylor; Chelsea Coon’s exploration of phenomenology and endurance performance; Alex Hedt’s critical analysis of Auslan interpretation in theatre; Paul Boye’s discussion of feminist post-humanism as it relates to Jean Francois Lyotard’s Les Immaterieux; and, a critical consideration of the ‘feverish’ institutional collecting practices of August Sander’s photography from Elizabeth Smith. These papers strikingly interrogate and critically analyse aspects of their field in a way that is sustained, deep and valuable for the fields under discussion.

Indicative of the interdisciplinarity of Currents, the first issue includes papers from students in visual art, art history, production, theatre studies and film. It takes to task various critical and social understandings of each of these discrete disciplines. Working through these exciting and various takes on the topics has allowed us to gain feedback from researchers who may be from laterally related fields, providing valuable and, at times, unusual insights into each of the papers.

Issue One, in a broad sense, seems to be characterised by questions that surround performance and institutional structures. There is an analysis of the workplace politics implicit in theatre from Madeline Taylor; Chelsea Coon’s exploration of phenomenology and endurance performance; Alex Hedt’s critical analysis of Auslan interpretation in theatre; Paul Boye’s discussion of feminist post-humanism as it relates to Jean Francois Lyotard’s Les Immaterieux; and, a critical consideration of the ‘feverish’ institutional collecting practices of August Sander’s photography from Elizabeth Smith. These papers strikingly interrogate and critically analyse aspects of their field in a way that is sustained, deep and valuable for the fields under discussion.

We return once again to the open

ended possibilities of Currents, of how we maintain, sustain, and go on,

in the context of both this health crisis and the digital itself; of how to

distribute our work to an emergent field while acknowledging the disparity of

possibility itself. This open-ended sensibility means that Currents, as

its title suggests, is about the wave that comes after the wave and that comes

before the wave that comes again and goes on. It is a praxis, a project, a

potential that is open source, open access, and opens itself out to what it can

develop into, over time and with different scholars, as their interests change

along with the possibilities of institutional collaboration. What we hope to

cultivate is a safe, inclusive, rigorous, dynamic and challenging intellectual

space that is able to consider and re-consider the arts in its richness,

fecundity and depth. That might be the qualities that help keep us current all

along.

Acknowledgements:

Currents could not have progressed or developed without the support, guidance and contributions of a range of people. We would like to thank our Advisory Board: Dr Clarissa Ball, Dr Darren Jorgensen, Dr Tessa Laird, Prof Su Baker, Dr Danny Butt and Vikki McInnes for their insights and critical support. We would like to thank our Editorial Committee: Paul Boyé, Emily Collett, Jonathan Graffam, Donna Lyon, Hannah Spracklan-Holl and Emanuel Rodríguez-Chaves for their conversation and support in the formative stages of Currents. In particular, we would like to thank Jonathan Graffam for his crucial contribution and energy; who initiated, directed and informed many of the formative editorial aspects of this journal. We would also like to extend our thanks to the Centre of Visual Art (CoVA), University of Melbourne and, through CoVA, the Dr Harold Schenberg Bequest for support and hosting of this new initiative. We would like to thank all our reviewers for their engaging and sustained feedback throughout the extraordinary circumstances of 2020. And most of all we would like to thank our authors for their ongoing and rigorous engagement with their practices and research throughout the development of these papers.

Acknowledgements:

Currents could not have progressed or developed without the support, guidance and contributions of a range of people. We would like to thank our Advisory Board: Dr Clarissa Ball, Dr Darren Jorgensen, Dr Tessa Laird, Prof Su Baker, Dr Danny Butt and Vikki McInnes for their insights and critical support. We would like to thank our Editorial Committee: Paul Boyé, Emily Collett, Jonathan Graffam, Donna Lyon, Hannah Spracklan-Holl and Emanuel Rodríguez-Chaves for their conversation and support in the formative stages of Currents. In particular, we would like to thank Jonathan Graffam for his crucial contribution and energy; who initiated, directed and informed many of the formative editorial aspects of this journal. We would also like to extend our thanks to the Centre of Visual Art (CoVA), University of Melbourne and, through CoVA, the Dr Harold Schenberg Bequest for support and hosting of this new initiative. We would like to thank all our reviewers for their engaging and sustained feedback throughout the extraordinary circumstances of 2020. And most of all we would like to thank our authors for their ongoing and rigorous engagement with their practices and research throughout the development of these papers.

About the authors:

Jeremy Eaton is an artist and writer based in Melbourne. He is the gallery coordinator of KINGS Artist-Run and the editorial coordinator of the Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art and an editorial committee member of un Magazine. Jeremy has exhibited throughout Australia participating in exhibitions at Sarah Scout Presents, Dominik Mersch Gallery, West Space, BUS Projects, CAVES, Margaret Lawrence Gallery and the Centre for Contemporary Photography. Jeremy has also written extensively for artists, galleries and publications including: the Ian Potter Museum of Art, Art + Australia, un Projects and Gertrude Contemporary.

Kelly Fliedner is a Perth-based writer and curator who is currently a PhD candidate at the University of Western Australia in the School of Design. Her research is, in a broad sense, interested in the discourses of postcolonialism and decolonisation as they manifest in, and are related to, contemporary art of South Asia. She is also the editor of Semaphore, a publication about art from Western Australia and convenes the Perth Festival’s Visual Art Writing Group. Kelly has worked for a broad range of organisations as a writer, artist, curator and editor including the Perth Festival, Tura New Music, Kochi-Muziris Biennale, Sydney Biennale, Next Wave Festival and West Space.

Jeremy Eaton is an artist and writer based in Melbourne. He is the gallery coordinator of KINGS Artist-Run and the editorial coordinator of the Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art and an editorial committee member of un Magazine. Jeremy has exhibited throughout Australia participating in exhibitions at Sarah Scout Presents, Dominik Mersch Gallery, West Space, BUS Projects, CAVES, Margaret Lawrence Gallery and the Centre for Contemporary Photography. Jeremy has also written extensively for artists, galleries and publications including: the Ian Potter Museum of Art, Art + Australia, un Projects and Gertrude Contemporary.

Kelly Fliedner is a Perth-based writer and curator who is currently a PhD candidate at the University of Western Australia in the School of Design. Her research is, in a broad sense, interested in the discourses of postcolonialism and decolonisation as they manifest in, and are related to, contemporary art of South Asia. She is also the editor of Semaphore, a publication about art from Western Australia and convenes the Perth Festival’s Visual Art Writing Group. Kelly has worked for a broad range of organisations as a writer, artist, curator and editor including the Perth Festival, Tura New Music, Kochi-Muziris Biennale, Sydney Biennale, Next Wave Festival and West Space.

Access and Aesthetics: Cultural Considerations in Interpreting Music and Theatre for Australia's d/Deaf Community

Alex Hedt

To cite this contribution:

Hedt, Alex. ‘Access and Aesthetics: Cultural Considerations in Interpreting Music and Theatre for Australia's d/Deaf Community’. Currents Journal Issue One (2020), https://currentsjournal.net/Access-and-Aesthetics.

Download this article ︎︎︎EPUB ︎︎︎PDF

Course of study:

Master of Music (Ethnomusicology), Melbourne Conservatorium of Music, University of Melbourne

Keywords:

Access aesthetics; Auslan-interpreted music; Deaf culture; disability arts; spectatorship

Abstract:

Since the 1980s, major musical theatre productions have included one-off Australian Sign Language (Auslan) interpreted shows in their Melbourne runs.1 This practice is now well established, with specialist interpreting agencies such as Auslan Stage Left existing specifically to meet this need. But Sarah Ward and Bec Matthews’s production The Legend of Queen Kong Episode II: Queen Kong in Outer Space, as performed at the Arts Centre Melbourne in January 2019, represents another approach to d/Deaf community access by building Auslan interpretation and captioning into the creative fabric of the work itself.2 Drawing on ethnographic fieldwork in theatrical Auslan interpreting, this paper compares these two approaches to interpreting and explores their socio-cultural implications for Deaf performers, audiences and prospective hearing collaborators.

Auslan sign for ‘monarch; queen; king’. Accessed from Auslan Signbank 9 September 2020: http://www.auslan.org.au/dictionary/words/queen-1.html.

I am ensconced in my cushioned seat, in a darkened theatre in Melbourne’s Arts Centre, as text scrolls up the projector screen in front and the familiar strains of Also sprach Zarathustra blare from the speakers. But this is no sci-fi film screening. Strauss yields to funk, and a silver-clad figure appears on screen. This is Deaf performer Asphyxia, playing the Motherboard, who ‘allows for communication between all systems and life-forms’ by signing the songs in Australian Sign Language (Auslan).1 The screen flashes rhythmically—‘1, 2, 3, 4!’—and a rock band leaps into action below. The Motherboard disappears, and a woman standing amongst the band begins to sign.

As its opening sequence illustrates, The Legend of Queen Kong Episode II: Queen Kong in Outer Space (hereafter, Queen Kong) belongs to a growing body of Australian works in what Bree Hadley calls a ‘disability theatre ecology’, a spectrum of practice which seeks to include d/Deaf and disabled people in a variety of ways.2 Queen Kong moves Auslan interpretation from its historical place side of stage into the spotlight, embedding it into the fabric of the performance. Asphyxia’s role as the conduit of communication, meanwhile, challenges popular conceptions of deafness as a hearing and communication deficit. By communicating in her preferred language, Auslan, she showcases the cultural-linguistic identity of the Deaf community.3 Furthermore, the work as a whole demonstrates how, as Carrie Sandahl explains, the phenomenology of Deafness can be used to inform and create art.4 An absent plot, a half-ape protagonist, nonsensical lyrics, and jumble of musical genres combine to confront hearing audiences with the same confusion that d/Deaf people face daily. The result makes good on the promise of disability arts ‘to wreak havoc, to disrupt and be loud and unruly.’5 But what would a d/Deaf attendee make of it?

In this paper, I examine the interaction between disability arts aesthetics and Deaf spectatorship, using Queen Kong as a case study. This addresses the ‘interesting limitation in the research’ recognised by Hadley: the lack of attention given to d/Deaf and disabled audiences.6 Hadley suggests that this gap is borne out of a tendency in audience research to examine cultural, rather than physical, heterogeneity.7 I propose that Deafness, with its combined sensory, physical and cultural attributes, adds additional challenges. Though the Deaf community’s right to Auslan interpretation is acknowledged in theory and practice, this accessibility measure has particular cultural and aesthetic connotations, which have gone relatively unstudied. Here, I draw on two years of ethnographic and archival research in Melbourne and Geelong—encompassing approximately a century’s worth of historical d/Deaf publications, fieldnotes from eighteen Deaf-led and d/Deaf-accessible events and six semi-structured interviews—on musical engagement among d/Deaf Victorians to articulate these connotations and highlight their implications for disability arts.

This paper begins with a brief survey of the ‘post-therapeutic’ and ‘aesthetically, socially, or politically subversive practices’ to which the aesthetic of Queen Kong nods, examining the concept of access aesthetics and how it is used to facilitate d/Deaf access.8 The following section draws on my participant-observation at several Deaf-led and d/Deaf-accessible events, many across the 2018 and 2019 Melbourne Fringe Festivals, and interviews with three Auslan interpreters who work in mainstage theatre interpreting to demonstrate that for Deaf audiences, utility and comprehension are themselves the most valued aesthetic principles. Informed by these insights, I finally use Queen Kong to highlight where access aesthetics, used indiscriminately, have the potential to alienate Deaf audiences. In doing so, I underscore the importance of recognising the discrete needs of the Deaf community in developing inclusive arts practice and research.

Before I continue, I thank members of the Australian Deaf community for sharing their language and culture. I am hard of hearing, and so have lived experience of deafness, but my Auslan is limited and I am not a member of the Deaf community. I acknowledge that my ability to communicate in English and to pass as hearing has shaped the way I see the world.9 I do not wish to engage in what Oliver calls ‘parasitic research’, but instead to advocate for the Deaf community.10

Disability Arts and Access Aesthetics

Here in Victoria, the landscape of disability arts practice includes a growing body of organisations which originally provided therapy or respite for people with disabilities but now primarily pursue ‘creative excellence through inclusive arts practices.’11 This concept of ‘excellence’ is not couched in terms of conventional, exclusionary aesthetic values, but instead, positions disability to ‘invigorate performance practice’.12 Julie McNamara, artistic director of United Kingdom disability arts company Vital Xposure, notes that this culture of innovation emerges from the problem-solving required for disabled artists to negotiate an often-inhospitable arts funding, training, policy and logistical landscape, rather than out of any innate desire to be novel or radical.13 One way to counter these barriers in performance practices, spearheaded by United Kingdom companies like Vital Xposure and Graeae, is by incorporating principles of access aesthetics, where accessibility measures are integrated into the fabric of the work from its inception.14

For the Deaf community, access aesthetics alters the experience of a spoken-language performance. Instead of the conventional practice of coming in on the day of a show and interpreting from beside the stage, interpreters—or, indeed, Deaf performers—become part of the rehearsal process and the show itself. As access aesthetics pioneer Jenny Sealey, artistic director of Graeae, explained, ‘As a Deaf person […] it has to be accessible for me, for my Deaf actors on stage; it also has to be accessible for a Deaf audience.’ It is easy to understand the appeal of integrated strategies in achieving this ideal: having the interpreter on stage results in a less ‘tennis-matchy’ experience for Deaf audiences, whilst introducing accessibility at an early stage of development renders it part of the aesthetic landscape instead of an ‘awkward appendage’.15

But access aesthetics is not merely visual or logistical: sign-language interpreting can be used to challenge the audist expectations of hearing audiences.16 Rawcus’s 2017 production Song for a Weary Throat, for instance, saw the interpreter tasked with the challenge of communicating a largely wordless score without using Auslan, with a result reportedly well-received by Deaf attendees.17 In the 2009 Vital Xposure production Crossings, each scene was preceded by a contextualising monologue in British Sign Language, without English translation. Recounting the process of staging the work, McNamara described the complaints that the lack of translation elicited from hearing audiences, despite the fact that these monologues actually levelled the playing field for Deaf audiences.18 Sign-language interpreting, live captioning, and auditory processing challenges all force communication delays upon d/Deaf people; information provided in advance lightens the load of ‘catching up’.19 Though far from exhaustive, these examples demonstrate how access aesthetics can provide access for Deaf audiences and, simultaneously, interrogate assumed hierarchies of ability.

However, speaking with Auslan interpreters during my fieldwork, I found that many of them were relatively unfamiliar with these practices. Instead, the bulk of their theatre work is Auslan-interpreted mainstage theatre, a practice established in Melbourne in the 1980s. As the following section illustrates, the practices developed in this field offer insight into the values that Australian Deaf audiences attach to theatre interpreting, and can therefore guide the evaluation of emerging practices.

Utility and Understanding: Conventional Auslan Interpreting For Music and Stage

For many Deaf Australians, Auslan interpreters perform essential services with evident utility, such as attending medical appointments and emergency press conferences. However, when this utility is transferred to a musical or theatrical environment, hearing people conceive of it differently, often misconstruing sign-language interpretation of song as a performance art.20 Despite this misconception, the concept of interpreting as utility remains central to Auslan music and theatre interpreters, as revealed in interpreters’ own accounts of their work.

With professional Auslan interpreters in chronically short supply, arts interpreting has often fallen to independent volunteers with relevant specialised knowledge.21 This was the catalyst for not-for-profit agency Auslan Stage Left, founded in Melbourne in 2012. Veteran interpreter Susan Emerson and Deaf theatre professional Medina Sumovic established the organisation to provide interpreting services, training and Deaf cultural consultancy to the arts sector.22 All three interpreters to whom I spoke work with Auslan Stage Left, which is valued within the Deaf community for its reputation of strong Deaf advocacy, its collaborative working model, and the Auslan proficiency of its interpreters.23

From the outset of the interpreting process, Auslan’s utilitarian function is evident, as when interpreters allocate roles. With only two interpreters for a full cast, continuity cannot always be preserved. When two characters allocated to the same interpreter engage in dialogue, interpreter Sally explained, the ‘spare’ interpreter will fill the gap, just for that scene.24 Interpreters convey only the performance elements that Deaf audiences can’t access any other way: the meaning of the text, and the dialogic nature of the interaction. Instead of playing or imitating characters, interpreters clarify details.

Despite this established distinction between interpreter and performer, the topic of characterisation permeated my conversations. The creative connotations of this term blur the line between the two: what does it mean to characterise whilst interpreting? The defining factor is the degree to which interpreters employ non-manual movements: gestures using body parts other than the hands. Whilst sometimes these movements contribute vital information to signs, as in the sign TIRED, which relies on facial expression, shoulder position, and the presence or absence of a sigh to convey a particular degree of tiredness, issues arise when these movements stray from linguistic meaning.25 For theatre interpreting, characterisation through non-manual movements is only relevant where it directly adds meaning to a Deaf viewer’s experience. Deaf viewers must continuously shift their gaze between actors and interpreters. Consequently, interpreters use subtle non-manual movements to develop a visual shorthand for each character which allows viewers to quickly deduce who is speaking. For instance, interpreter Max used stance to distinguish between characters Tick and Felicia in Priscilla: Queen of the Desert: ‘Like, Tick’s a bit more manly than Felicia, so with Felicia it was all a bit more feminine, legs closed, a bit more dramatic, without doing what he was doing.’26 In doing this, he enhances Deaf viewers’ understanding of the action taking place.

As its opening sequence illustrates, The Legend of Queen Kong Episode II: Queen Kong in Outer Space (hereafter, Queen Kong) belongs to a growing body of Australian works in what Bree Hadley calls a ‘disability theatre ecology’, a spectrum of practice which seeks to include d/Deaf and disabled people in a variety of ways.2 Queen Kong moves Auslan interpretation from its historical place side of stage into the spotlight, embedding it into the fabric of the performance. Asphyxia’s role as the conduit of communication, meanwhile, challenges popular conceptions of deafness as a hearing and communication deficit. By communicating in her preferred language, Auslan, she showcases the cultural-linguistic identity of the Deaf community.3 Furthermore, the work as a whole demonstrates how, as Carrie Sandahl explains, the phenomenology of Deafness can be used to inform and create art.4 An absent plot, a half-ape protagonist, nonsensical lyrics, and jumble of musical genres combine to confront hearing audiences with the same confusion that d/Deaf people face daily. The result makes good on the promise of disability arts ‘to wreak havoc, to disrupt and be loud and unruly.’5 But what would a d/Deaf attendee make of it?

In this paper, I examine the interaction between disability arts aesthetics and Deaf spectatorship, using Queen Kong as a case study. This addresses the ‘interesting limitation in the research’ recognised by Hadley: the lack of attention given to d/Deaf and disabled audiences.6 Hadley suggests that this gap is borne out of a tendency in audience research to examine cultural, rather than physical, heterogeneity.7 I propose that Deafness, with its combined sensory, physical and cultural attributes, adds additional challenges. Though the Deaf community’s right to Auslan interpretation is acknowledged in theory and practice, this accessibility measure has particular cultural and aesthetic connotations, which have gone relatively unstudied. Here, I draw on two years of ethnographic and archival research in Melbourne and Geelong—encompassing approximately a century’s worth of historical d/Deaf publications, fieldnotes from eighteen Deaf-led and d/Deaf-accessible events and six semi-structured interviews—on musical engagement among d/Deaf Victorians to articulate these connotations and highlight their implications for disability arts.

This paper begins with a brief survey of the ‘post-therapeutic’ and ‘aesthetically, socially, or politically subversive practices’ to which the aesthetic of Queen Kong nods, examining the concept of access aesthetics and how it is used to facilitate d/Deaf access.8 The following section draws on my participant-observation at several Deaf-led and d/Deaf-accessible events, many across the 2018 and 2019 Melbourne Fringe Festivals, and interviews with three Auslan interpreters who work in mainstage theatre interpreting to demonstrate that for Deaf audiences, utility and comprehension are themselves the most valued aesthetic principles. Informed by these insights, I finally use Queen Kong to highlight where access aesthetics, used indiscriminately, have the potential to alienate Deaf audiences. In doing so, I underscore the importance of recognising the discrete needs of the Deaf community in developing inclusive arts practice and research.

Before I continue, I thank members of the Australian Deaf community for sharing their language and culture. I am hard of hearing, and so have lived experience of deafness, but my Auslan is limited and I am not a member of the Deaf community. I acknowledge that my ability to communicate in English and to pass as hearing has shaped the way I see the world.9 I do not wish to engage in what Oliver calls ‘parasitic research’, but instead to advocate for the Deaf community.10

Disability Arts and Access Aesthetics

Here in Victoria, the landscape of disability arts practice includes a growing body of organisations which originally provided therapy or respite for people with disabilities but now primarily pursue ‘creative excellence through inclusive arts practices.’11 This concept of ‘excellence’ is not couched in terms of conventional, exclusionary aesthetic values, but instead, positions disability to ‘invigorate performance practice’.12 Julie McNamara, artistic director of United Kingdom disability arts company Vital Xposure, notes that this culture of innovation emerges from the problem-solving required for disabled artists to negotiate an often-inhospitable arts funding, training, policy and logistical landscape, rather than out of any innate desire to be novel or radical.13 One way to counter these barriers in performance practices, spearheaded by United Kingdom companies like Vital Xposure and Graeae, is by incorporating principles of access aesthetics, where accessibility measures are integrated into the fabric of the work from its inception.14

For the Deaf community, access aesthetics alters the experience of a spoken-language performance. Instead of the conventional practice of coming in on the day of a show and interpreting from beside the stage, interpreters—or, indeed, Deaf performers—become part of the rehearsal process and the show itself. As access aesthetics pioneer Jenny Sealey, artistic director of Graeae, explained, ‘As a Deaf person […] it has to be accessible for me, for my Deaf actors on stage; it also has to be accessible for a Deaf audience.’ It is easy to understand the appeal of integrated strategies in achieving this ideal: having the interpreter on stage results in a less ‘tennis-matchy’ experience for Deaf audiences, whilst introducing accessibility at an early stage of development renders it part of the aesthetic landscape instead of an ‘awkward appendage’.15

But access aesthetics is not merely visual or logistical: sign-language interpreting can be used to challenge the audist expectations of hearing audiences.16 Rawcus’s 2017 production Song for a Weary Throat, for instance, saw the interpreter tasked with the challenge of communicating a largely wordless score without using Auslan, with a result reportedly well-received by Deaf attendees.17 In the 2009 Vital Xposure production Crossings, each scene was preceded by a contextualising monologue in British Sign Language, without English translation. Recounting the process of staging the work, McNamara described the complaints that the lack of translation elicited from hearing audiences, despite the fact that these monologues actually levelled the playing field for Deaf audiences.18 Sign-language interpreting, live captioning, and auditory processing challenges all force communication delays upon d/Deaf people; information provided in advance lightens the load of ‘catching up’.19 Though far from exhaustive, these examples demonstrate how access aesthetics can provide access for Deaf audiences and, simultaneously, interrogate assumed hierarchies of ability.

However, speaking with Auslan interpreters during my fieldwork, I found that many of them were relatively unfamiliar with these practices. Instead, the bulk of their theatre work is Auslan-interpreted mainstage theatre, a practice established in Melbourne in the 1980s. As the following section illustrates, the practices developed in this field offer insight into the values that Australian Deaf audiences attach to theatre interpreting, and can therefore guide the evaluation of emerging practices.

Utility and Understanding: Conventional Auslan Interpreting For Music and Stage

For many Deaf Australians, Auslan interpreters perform essential services with evident utility, such as attending medical appointments and emergency press conferences. However, when this utility is transferred to a musical or theatrical environment, hearing people conceive of it differently, often misconstruing sign-language interpretation of song as a performance art.20 Despite this misconception, the concept of interpreting as utility remains central to Auslan music and theatre interpreters, as revealed in interpreters’ own accounts of their work.

With professional Auslan interpreters in chronically short supply, arts interpreting has often fallen to independent volunteers with relevant specialised knowledge.21 This was the catalyst for not-for-profit agency Auslan Stage Left, founded in Melbourne in 2012. Veteran interpreter Susan Emerson and Deaf theatre professional Medina Sumovic established the organisation to provide interpreting services, training and Deaf cultural consultancy to the arts sector.22 All three interpreters to whom I spoke work with Auslan Stage Left, which is valued within the Deaf community for its reputation of strong Deaf advocacy, its collaborative working model, and the Auslan proficiency of its interpreters.23

From the outset of the interpreting process, Auslan’s utilitarian function is evident, as when interpreters allocate roles. With only two interpreters for a full cast, continuity cannot always be preserved. When two characters allocated to the same interpreter engage in dialogue, interpreter Sally explained, the ‘spare’ interpreter will fill the gap, just for that scene.24 Interpreters convey only the performance elements that Deaf audiences can’t access any other way: the meaning of the text, and the dialogic nature of the interaction. Instead of playing or imitating characters, interpreters clarify details.

Despite this established distinction between interpreter and performer, the topic of characterisation permeated my conversations. The creative connotations of this term blur the line between the two: what does it mean to characterise whilst interpreting? The defining factor is the degree to which interpreters employ non-manual movements: gestures using body parts other than the hands. Whilst sometimes these movements contribute vital information to signs, as in the sign TIRED, which relies on facial expression, shoulder position, and the presence or absence of a sigh to convey a particular degree of tiredness, issues arise when these movements stray from linguistic meaning.25 For theatre interpreting, characterisation through non-manual movements is only relevant where it directly adds meaning to a Deaf viewer’s experience. Deaf viewers must continuously shift their gaze between actors and interpreters. Consequently, interpreters use subtle non-manual movements to develop a visual shorthand for each character which allows viewers to quickly deduce who is speaking. For instance, interpreter Max used stance to distinguish between characters Tick and Felicia in Priscilla: Queen of the Desert: ‘Like, Tick’s a bit more manly than Felicia, so with Felicia it was all a bit more feminine, legs closed, a bit more dramatic, without doing what he was doing.’26 In doing this, he enhances Deaf viewers’ understanding of the action taking place.

However, excessive gestural characterisation detracts from a Deaf person’s experience. Deaf viewers associate these extraneous movement with the interpreter rather than the character. For instance, Max’s attempt to portray a character as a drug addict by sniffing fell flat, with the audience thinking Max himself had a cold.27 This association further delineates interpreters’ roles in the Deaf cultural hierarchy. If she were to overdo it, Sally thought, she would be told, ‘you’re not a Deafie, you’re up there for us, calm down a little bit.’28 Excessive acting would put her in the limelight, and therefore, draw her away from her utilitarian, service-based role.

In musical theatre interpreting, even the music itself assumes a utilitarian function. Although interpreters note musical material, for them it exists primarily to inform the lyrics’ subtext. Musical elements are not isolated, but considered for their overall effect. Expressive techniques can be connected to musical elements—shifting to an upper register might be matched with a ‘rise onto tippy-toes… or… sign a little bit higher’—but only when they advance the narrative.29

Auslan Stage Left interpreters collaborate with Deaf consultants, who provide feedback from their perspective as Deaf people who use Auslan as their primary language. Examining the nature of this feedback, we understand that in Auslan, aesthetic appeal is actually measured by linguistic utility. ‘Looking good’ is synonymous with ‘being understood’, with particular signs chosen for both visual balance and linguistic connotations.30 Max described an example from his work on Aladdin, where the consultant suggested changing the translation of a lyric from OPPORTUNITY NOTHING… NOTHING to OPPORTUNITY GONE, OPPORTUNITY GONE.31 When Max explained why the new translation was better, he told me: ‘And so, like that, I just go, that looks so much better, because of that Deaf eye […] and, like, a good understanding of what that song’s trying to say.’32 For Max, a first-language Auslan user as well as an interpreter, this appeal was not just visual: it looked better precisely because the newly-chosen signs better reflected the desired meaning. Although a hearing person might interpret Max’s words as referring only to the visual appeal of Auslan, for Deaf people, ‘looking good’ is not purely an aesthetic construct. As this and the previous examples reveal, aesthetic decisions in Auslan, and by extension, in Deaf arts, are meaningless unless they contribute to a Deaf audience’s understanding. Furthermore, conventional Auslan interpreting is not a performance art. It instead communicates the meaning embedded in performance. Queen Kong, as we see below, takes a different approach. Can it do so and still provide meaningful access to the Deaf community?

‘Don’t worry, nobody else understands what is happening either’: Deaf Access Aesthetics in Queen Kong33

Queen Kong is a theatrical work, described by its creators as a ‘queer, sci-fi, rock concert’, which ‘tells the story of an immortal being, part-rock and part ape, who journeys through time and space to discover what it means to be human’.34 Title character Queen Kong, alter-ego of hearing cabaret artist Sarah Ward, punctuates this journey with songs accompanied by musical director Bec Matthews and onstage band The HOMOsapiens, simultaneously performed in Auslan by Deaf artist Asphyxia. Its January 2019 Midsumma Festival production at Arts Centre Melbourne was Queen Kong’s second iteration. It premiered at Adelaide Fringe without Asphyxia’s role. Keen to include d/Deaf and disabled audiences from the outset, Ward and Matthews sought feedback from Jess Thom, best known as the co-founder of Touretteshero. Thom reportedly noted that the work was broadly inclusive, but did not centre accessibility.35 Enter Asphyxia, a friend of Matthews’s: Ward and Matthews decided that the most culturally sensitive way to ensure Deaf accessibility was to write her into the cast.36 However, despite a Deaf-friendly advertising campaign with Auslan videos, I saw no signing Deaf people at the performance I attended, unlike at other events I have attended during my fieldwork.37 The following discussion examines this absence by critiquing Queen Kong’s access measures as they might be understood in Deaf culture.

Ward and Matthews describe Asphyxia’s character as Queen Kong’s primary Deaf accessibility device.38 However, this description hinges on a conflation of the roles of interpreter and performer. Asphyxia appears not to make sense of the material, instead dancing and engaging more freely with difficult-to-translate nonsensical English wordplay. We see this in songs like Nomo Fomo and I’m a Blancmange, where even the original English lyrics are incoherent. These lyrics call into question Ward and Matthews’s claim that they had rewritten the script to work in Auslan.39 Asphyxia’s signing is more expressive than communicative. In the first version of Nomo Fomo, she interprets the non-lyrical vocalisation ‘do do do’ with rhythmically alternating D and O signs, but in the reprise, she replaces this with a repeat of an earlier verse. Whilst this is a known strategy in artistic song signing, it strays from purely functional interpretation.40 To evaluate the success of Asphyxia’s role, we must first understand whether it was intended primarily as an access measure for a Deaf audience or for her as a Deaf performer. Based on the aesthetic principles explained earlier, its inability to convey meaning—even in a deliberately nonsensical work like this—hinders its utility for a Deaf audience. However, this reading changes somewhat if we understand the Motherboard character as an opportunity for Deaf performance. Reclaiming their native language from hearing discourses, many in the Deaf community agree that Deaf performers are free to take creative license with Auslan in ways that hearing signers, including interpreters, are not.41 Asphyxia’s performance might be positively received within the community on those grounds. That said, esteemed performers of Deaf art forms such as storytelling (described as ‘smooth signers’) are lauded for their ability to bring a story to life, a concept which itself depends on comprehensibility.42 Though I cannot speak definitively for a hypothetical Deaf audience, this brief discussion illuminates complexities and debates that may not be obvious to someone providing Deaf access for the first time, as Ward and Matthews did here.

In making the case for disability arts, Sandahl laments the relative paucity of theatre artists who ‘think about ways to disperse language into space through multiple channels’.43 Queen Kong displays evidence of this thinking, conveying linguistic and musical materials not only through Auslan interpretation but also by visual and textual means. One method is the manipulation of Asphyxia’s image on the projector display, used to represent texture. As different parts enter, her image multiplies, and the screen also pulses to indicate tempo changes. The concept of music for its own sake in Queen Kong is further reinforced through written descriptions of genre and musical terminology in both the program (or ‘zine’) and on-screen captioning. Both employ genre descriptions bordering on the nonsensical, as in the song Truck Stop: ‘Driving surf-pop with a funk groove chorus and Loony Bop B-section.’44 Whilst Hadley suggests that communicating information across multiple modes cultivates awareness of one’s fellow spectators, I question how true this might be for Deaf audiences in this context. The visual elements, though interesting, have no inherent connection with the musical material; furthermore, the written musical terminology excludes by assuming prior musical knowledge beyond even many hearing people. As Queen Kong deliberately fosters a sense of chaos, perhaps nobody is supposed to understand this terminology. Indeed, it could be read as a commentary on Asphyxia’s own inability to understand musical jargon. However, the meta-reflective subtext could easily be lost on a Deaf audience member, who might assume that the hearing people around them do understand. Whilst the use of multiple channels might challenge hearing audiences, it does little to enhance Deaf access.

Conclusions

In Queen Kong, the same attributes that offer ‘provocative, parodic and unconventional representations’ of Deafness and Deaf cultural perspectives run the risk of excluding Deaf audiences.45 Although the work appears to respond to Sandahl’s call-to-arms by communicating across multiple channels, including in Auslan, it reveals the importance of understanding the reasons for doing so. Queen Kong falls short of the access aesthetic ideal championed by companies like Graeae: disability-led, innovative and accessible to both performer and audience. However, this brief case study is not a critique of access aesthetics itself. Instead, it demonstrates the urgent need for critical review and research into Deaf and disability arts practices in a climate where engaging with these practices is increasingly ‘fashionable’ among hearing and able-bodied practitioners.46 Despite Asphyxia’s input, Queen Kong is predominantly a hearing-led work; whilst it includes a Deaf performer, and encourages hearing people to reconsider audist assumptions, it mobilises Deaf sensory perspectives with only a cursory glance at Deaf community interests. Therefore, its shortcomings emphasise the ‘ethical imperative’ of disability-led and Deaf-led approaches.47 These conclusions only become visible when examining the nature of culturally Deaf spectatorship. By foregrounding some of the Deaf cultural values embedded in historical arts interpreting practices—interpreting as utility, the difference between interpreting and performing and the aesthetic of comprehensibility—this preliminary analysis offers some discussion points for further research.

Acknowledgements:

I thank Nicholas Tochka and Anthea Skinner for their guidance and suggestions on early versions of this material, as well as the journal’s anonymous reviewers for their helpful feedback.

Notes:

About the author: Alex Hedt is a research assistant at the Melbourne Conservatorium of Music, The University of Melbourne, where her Master of Music (Ethnomusicology) thesis is currently under examination. Her thesis presents a history of musical practice in the Victorian Deaf community from 1884 to the present day and an ethnographic exploration of musical engagement amongst d/Deaf Australians. Informed by prior studies in music education, Alex’s broader research interests include disability arts cultures, choral music, diversity and accessibility in music, and the ways in which musical institutions construct and portray musical ability. She is also an active performer, singing with ensembles including the Australian Chamber Choir.

In musical theatre interpreting, even the music itself assumes a utilitarian function. Although interpreters note musical material, for them it exists primarily to inform the lyrics’ subtext. Musical elements are not isolated, but considered for their overall effect. Expressive techniques can be connected to musical elements—shifting to an upper register might be matched with a ‘rise onto tippy-toes… or… sign a little bit higher’—but only when they advance the narrative.29

Auslan Stage Left interpreters collaborate with Deaf consultants, who provide feedback from their perspective as Deaf people who use Auslan as their primary language. Examining the nature of this feedback, we understand that in Auslan, aesthetic appeal is actually measured by linguistic utility. ‘Looking good’ is synonymous with ‘being understood’, with particular signs chosen for both visual balance and linguistic connotations.30 Max described an example from his work on Aladdin, where the consultant suggested changing the translation of a lyric from OPPORTUNITY NOTHING… NOTHING to OPPORTUNITY GONE, OPPORTUNITY GONE.31 When Max explained why the new translation was better, he told me: ‘And so, like that, I just go, that looks so much better, because of that Deaf eye […] and, like, a good understanding of what that song’s trying to say.’32 For Max, a first-language Auslan user as well as an interpreter, this appeal was not just visual: it looked better precisely because the newly-chosen signs better reflected the desired meaning. Although a hearing person might interpret Max’s words as referring only to the visual appeal of Auslan, for Deaf people, ‘looking good’ is not purely an aesthetic construct. As this and the previous examples reveal, aesthetic decisions in Auslan, and by extension, in Deaf arts, are meaningless unless they contribute to a Deaf audience’s understanding. Furthermore, conventional Auslan interpreting is not a performance art. It instead communicates the meaning embedded in performance. Queen Kong, as we see below, takes a different approach. Can it do so and still provide meaningful access to the Deaf community?

‘Don’t worry, nobody else understands what is happening either’: Deaf Access Aesthetics in Queen Kong33

Queen Kong is a theatrical work, described by its creators as a ‘queer, sci-fi, rock concert’, which ‘tells the story of an immortal being, part-rock and part ape, who journeys through time and space to discover what it means to be human’.34 Title character Queen Kong, alter-ego of hearing cabaret artist Sarah Ward, punctuates this journey with songs accompanied by musical director Bec Matthews and onstage band The HOMOsapiens, simultaneously performed in Auslan by Deaf artist Asphyxia. Its January 2019 Midsumma Festival production at Arts Centre Melbourne was Queen Kong’s second iteration. It premiered at Adelaide Fringe without Asphyxia’s role. Keen to include d/Deaf and disabled audiences from the outset, Ward and Matthews sought feedback from Jess Thom, best known as the co-founder of Touretteshero. Thom reportedly noted that the work was broadly inclusive, but did not centre accessibility.35 Enter Asphyxia, a friend of Matthews’s: Ward and Matthews decided that the most culturally sensitive way to ensure Deaf accessibility was to write her into the cast.36 However, despite a Deaf-friendly advertising campaign with Auslan videos, I saw no signing Deaf people at the performance I attended, unlike at other events I have attended during my fieldwork.37 The following discussion examines this absence by critiquing Queen Kong’s access measures as they might be understood in Deaf culture.

Ward and Matthews describe Asphyxia’s character as Queen Kong’s primary Deaf accessibility device.38 However, this description hinges on a conflation of the roles of interpreter and performer. Asphyxia appears not to make sense of the material, instead dancing and engaging more freely with difficult-to-translate nonsensical English wordplay. We see this in songs like Nomo Fomo and I’m a Blancmange, where even the original English lyrics are incoherent. These lyrics call into question Ward and Matthews’s claim that they had rewritten the script to work in Auslan.39 Asphyxia’s signing is more expressive than communicative. In the first version of Nomo Fomo, she interprets the non-lyrical vocalisation ‘do do do’ with rhythmically alternating D and O signs, but in the reprise, she replaces this with a repeat of an earlier verse. Whilst this is a known strategy in artistic song signing, it strays from purely functional interpretation.40 To evaluate the success of Asphyxia’s role, we must first understand whether it was intended primarily as an access measure for a Deaf audience or for her as a Deaf performer. Based on the aesthetic principles explained earlier, its inability to convey meaning—even in a deliberately nonsensical work like this—hinders its utility for a Deaf audience. However, this reading changes somewhat if we understand the Motherboard character as an opportunity for Deaf performance. Reclaiming their native language from hearing discourses, many in the Deaf community agree that Deaf performers are free to take creative license with Auslan in ways that hearing signers, including interpreters, are not.41 Asphyxia’s performance might be positively received within the community on those grounds. That said, esteemed performers of Deaf art forms such as storytelling (described as ‘smooth signers’) are lauded for their ability to bring a story to life, a concept which itself depends on comprehensibility.42 Though I cannot speak definitively for a hypothetical Deaf audience, this brief discussion illuminates complexities and debates that may not be obvious to someone providing Deaf access for the first time, as Ward and Matthews did here.

In making the case for disability arts, Sandahl laments the relative paucity of theatre artists who ‘think about ways to disperse language into space through multiple channels’.43 Queen Kong displays evidence of this thinking, conveying linguistic and musical materials not only through Auslan interpretation but also by visual and textual means. One method is the manipulation of Asphyxia’s image on the projector display, used to represent texture. As different parts enter, her image multiplies, and the screen also pulses to indicate tempo changes. The concept of music for its own sake in Queen Kong is further reinforced through written descriptions of genre and musical terminology in both the program (or ‘zine’) and on-screen captioning. Both employ genre descriptions bordering on the nonsensical, as in the song Truck Stop: ‘Driving surf-pop with a funk groove chorus and Loony Bop B-section.’44 Whilst Hadley suggests that communicating information across multiple modes cultivates awareness of one’s fellow spectators, I question how true this might be for Deaf audiences in this context. The visual elements, though interesting, have no inherent connection with the musical material; furthermore, the written musical terminology excludes by assuming prior musical knowledge beyond even many hearing people. As Queen Kong deliberately fosters a sense of chaos, perhaps nobody is supposed to understand this terminology. Indeed, it could be read as a commentary on Asphyxia’s own inability to understand musical jargon. However, the meta-reflective subtext could easily be lost on a Deaf audience member, who might assume that the hearing people around them do understand. Whilst the use of multiple channels might challenge hearing audiences, it does little to enhance Deaf access.

Conclusions

In Queen Kong, the same attributes that offer ‘provocative, parodic and unconventional representations’ of Deafness and Deaf cultural perspectives run the risk of excluding Deaf audiences.45 Although the work appears to respond to Sandahl’s call-to-arms by communicating across multiple channels, including in Auslan, it reveals the importance of understanding the reasons for doing so. Queen Kong falls short of the access aesthetic ideal championed by companies like Graeae: disability-led, innovative and accessible to both performer and audience. However, this brief case study is not a critique of access aesthetics itself. Instead, it demonstrates the urgent need for critical review and research into Deaf and disability arts practices in a climate where engaging with these practices is increasingly ‘fashionable’ among hearing and able-bodied practitioners.46 Despite Asphyxia’s input, Queen Kong is predominantly a hearing-led work; whilst it includes a Deaf performer, and encourages hearing people to reconsider audist assumptions, it mobilises Deaf sensory perspectives with only a cursory glance at Deaf community interests. Therefore, its shortcomings emphasise the ‘ethical imperative’ of disability-led and Deaf-led approaches.47 These conclusions only become visible when examining the nature of culturally Deaf spectatorship. By foregrounding some of the Deaf cultural values embedded in historical arts interpreting practices—interpreting as utility, the difference between interpreting and performing and the aesthetic of comprehensibility—this preliminary analysis offers some discussion points for further research.

Acknowledgements:

I thank Nicholas Tochka and Anthea Skinner for their guidance and suggestions on early versions of this material, as well as the journal’s anonymous reviewers for their helpful feedback.

Notes:

- In 1985, the Victorian State Govermnent provided a grant funding Auslan interpreters for six musical theatre productions over the following year. See Adult Deaf Society of Victoria, Deaf Talkabout, December 1985, 5.

-

I follow conventions in Deaf scholarship, using lowercase ‘deaf’ to represent the physical condition, capitalised ‘Deaf’ when referring to the cultural-linguistic minority group, and d/Deaf when people who identify in either category are implicated, as first proposed by James Woodward, How You Gonna Get to Heaven if You Can’t Talk With Jesus: On Depathologizing Deafness (Silver Spring, MD: TJ Publishers, Inc., 1982).

-

Queen Kong and the HOMOsapiens, The Legend of Queen Kong Episode II: Queen Kong in Outer Space. Info. Data. What’s What. Low-Down. (Melbourne: Arts Centre Melbourne, 2019), 14.

-

Bree Hadley, ‘Disability Theatre in Australia: A Survey and a Sector Ecology’, Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance 22 (2017), 308.

-

Paddy Ladd, Understanding Deaf Culture: In Search of Deafhood (Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, 2003).

-

Carrie Sandahl, ‘Considering Disability: Disability Phenomenology’s Role in Revolutionizing Theatrical Space’, Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism (2002), 18.

-

Bree Hadley et al., ‘Conclusion: Practicing Interdependency, Sharing Vulnerability, Celebrating Complexity – the Future of Disability Arts, Culture, and Media Research’, in The Routledge Handbook of Disability Arts, Culture, and Media, ed. Bree Hadley and Donna McDonald (Abingdon: Routledge, 2018), 370.

-

Bree Hadley, ‘Participation, Politics and Provocations: People with Disabilities as Non-Conciliatory Audiences’, Participations: Journal of Audience and Reception Studies 12 (2015), 155.

-

Hadley, ‘Participation, Politics and Provocations’, 155.

-

Hadley, ‘Disability Theatre in Australia’, 311-13.

-

Owen Wrigley, The Politics of Deafness (Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press, 1996), 14.

-

Mike Oliver, ‘Final Accounts and the Parasite People’, in Disability Discourse, ed. Mairian Corker and Sally French (Philadelphia, Open University Press, 1999), 184.

-

Sarah Austin et al., Beyond Access: The Creative Case for Inclusive Arts (Melbourne: Arts Access Victoria, 2015), www.artsaccess.com.au/beyond-access/, 43.

-

Sandahl, ‘Considering Disabiilty’, 18.

-

Sarah Austin et al., ‘The Last Avant Garde?’, in The Routledge Handbook of Disability Arts, Culture, and Media, ed. Bree Hadley and Donna McDonald (Abingdon: Routledge, 2018), 259.

-

Kirsty Johnston, ‘Great Reckonings in More Accessible Rooms: The Provocative Reimaginings of Disability Theatre’, The Routledge Handbook of Disability Arts, Culture, and Media, ed. Bree Hadley and Donna McDonald (Abingdon: Routledge, 2018), 32.

-

Sandahl, ‘Considering Disability’, 26; Mike, Skype interview with author, 25 June 2019.

- Audism, a term coined by Deaf scholar Tom Humphries, refers to a form of prejudice based on the ability to hear, and the assumption of hearing values. See Tom Humphries, ‘Communicating across Cultures (Deaf/Hearing) and Language Learning’ (Ph.D., Cincinnati, OH, Union Graduate School, 1977).

-

Austin et al., ‘The Last Avant Garde?’, 258-9.

-

Julie McNamara, ‘Cripping It Up! Unruly Bodies and Minds Unleashed’ (University of Melbourne Miegunyah Distinguished Fellow Lecture, Southbank, Australia, 3 April 2019).

-

McNamara, ‘Cripping It Up!’

-

This phenomenon has received recent attention in the media, with the viral popularity of American Sign Language interpreter Amber Galloway Gallego’s work with rapper Twista. See Lilit Marcus, ‘Twista ASL Interpreter’s Viral Moment Misses the Point’, CNN, 23 August 2019, https://www.cnn.com/2019/08/23/opinions/asl-interpreter-twista-video-deaf-culture-marcus/index.html.

-

This gap in provision was first recognised by the Victorian Deaf Society, now Expression Australia, in 1976, as they advertised for a list of additional volunteer interpreters in Society magazine Deaf Talkabout, June 1976, 5.

-

Auslan Stage Left, ‘About Auslan Stage Left’, Auslan Stage Left, accessed 21 October 2019, http://www.auslanstageleft.com.au/the-team/auslan-stage-left/.

-

Max, Skype interview with author, 25 June 2019. All participants have been assigned pseudonyms in this paper for privacy.

-

Sally, phone interview with author, 6 August 2019.

-

In keeping with Auslan linguistic convention, English words used to represent signs are fully capitalised, acknowledging that the word does not necessarily correspond with English. This is called glossing. See Trevor Johnston and Adam Schembri, Australian Sign Language (Auslan) : An Introduction to Sign Language Linguistics (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2007), xiv, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/unimelb/detail.action?docID=288448. The nuances of the TIRED sign were explained to me by Sally, phone interview, 6 August 2019.

-

Max, Skype interview with author, 25 June 2019.

-

Max, Skype interview with author, 25 June 2019.

-

Sally, phone interview with author, 6 August 2019.

-

Sally, phone interview with author, 6 August 2019.

-

Max, Skype interview with author, 25 June 2019.

-

Max, Skype interview with author, 25 June 2019.

-

Max, Skype interview with author, 25 June 2019.

-

Queen Kong and the HOMOsapiens, The Legend of Queen Kong Episode II: Queen Kong in Outer Space. Info. Data. What’s What. Low-Down (Melbourne: Arts Centre Melbourne, 2019), 3.

-

Queen Kong and the HOMOsapiens, The Legend of Queen Kong, 3.

-

Sarah Ward et al., ‘Learnings on Embedded Access’ (Panel discussion at the Kiln Festival, Melbourne, Australia, 17 June 2019).

-

Ward et al., ‘Learnings on Embedded Access’.

-

Deaf-friendly marketing for this event extended to YouTube. See Arts Centre Melbourne, January 9, 2019, Asphyxia in The Legend of Queen Kong | 16 - 20 January, YouTube video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U3D76ArFA9k

-

Ward et al., ‘Learnings on Embedded Access’.

-

Ward et al., ‘Learnings on Embedded Access’.

-

Personal communication with a music teacher who works with d/Deaf children, 4 June 2019.

-

This was a point discussed by Deaf dancer Anna Seymour at the relaunch of her company The Delta Project, where she argued that she, as a Deaf woman, had the creative licence to use Auslan as a visual resource to inform her dance work. The Delta Project relaunch, dance performance, dancers Anna Seymour, Amanda Lever and Kyall Shanks, chor. Stephanie Lake, Chunky Move, Southbank, 15 November 2019.

-

Ben Bahan, ‘Face-to-Face Tradition in the American Deaf Community: Dynamics of the Teller, the Tale, and the Audience’, in Signing the Body Poetic, ed. H-Dirksen Bauman, Heidi Rose, and Jennifer Nelson (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006), 26.

-

Sandahl, ‘Considering Disability’, 26.

- Queen Kong and the HOMOsapiens, The Legend of Queen Kong, 11.

-

Bree Hadley and Donna McDonald, ‘Introduction: Disability Arts, Culture, and Media Studies – Mapping a Maturing Field’, in The Routledge Handbook of Disability Arts, Culture, and Media, ed. Bree Hadley and Donna McDonald (Abingdon: Routledge, 2018), 2.

-

Austin et al., Beyond Access, 44; Hadley, ‘Disability Theatre in Australia’, 317.

-

Hadley, ‘Disability Theatre in Australia’, 312.

The Inhuman Condition: Jean-François Lyotard’s Les Immatériaux and Technological Sublime

Paul Boyé

To cite this contribution:

Boyé, Paul. ‘The Inhuman Condition: Jean-François Lyotard’s Les Immatériaux and Technological Sublime’ . Currents Journal Issue One (2020), https://currentsjournal.net/The-Inhuman-Condition.

Download this article ︎︎︎EPUB ︎︎︎PDF

Course of study:

Doctor of Philosophy, School of Design, Univeristy of Western Australia

Keywords: Lyotard, sublime, postmodern, Les Immatériaux, posthuman, art and technology, curation, relativism and reductionism, nihilism, anti-capitalism.

Abstract:

Jean-François Lyotard engaged with art and technology at several points across his philosophical project. This article will analyse these engagements, playing close attention to how technological development re-oriented how the philosopher’s aesthetic philosophy of the sublime, along with his considerations of anthropocentricism vis-à-vis a concept of the ‘inhuman’. His curatorial effort as a part of Les Immatériaux is a central concern of the essay, as it is taken to be a practical experiment with many of his ideas. The exhibition is argued to be a pre-eminent curatorial experiment that anticipated much of the posthuman discourse advocated by contemporary artists today.

Bracha L. Ettinger , Jean-François Lyotard (2007). Accessed from Wikimedia Commons 28 September 2020: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jean-Francois_Lyotard_cropped.jpg

Bracha L. Ettinger , Jean-François Lyotard (2007). Accessed from Wikimedia Commons 28 September 2020: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jean-Francois_Lyotard_cropped.jpg

The task of this essay is to broadly examine

the various engagements with art, technology and humanism performed by French

philosopher Jean-François Lyotard. Along with Lyotard’s published philosophical

writing, this essay will pay close attention to Les Immatériaux—an

exhibition that Lyotard co-curated with designer Thierry Chaput—which will be

considered to mark a crucial intersection for the philosopher and his

considerations of the technological world as it evolved around him. Two key

terms will emerge across this examination: ‘inhuman’ and ‘sublime’. Both terms

invoke a clear philosophical tone, but their relationship—arguably analogous to

the relationship between art and technology itself—is complex and entangled.

While there are many engagements with art and technology contemporary to

Lyotard, it is the non-anthropocentric tenor of which Lyotard characterises his

engagement that will be emphasised here. The inhuman, as something never quite

human but nevertheless surrounding the conceptual categories of what a human is

taken to be, offers a resource to radically de-center humanist assumptions. Additionally

the sublime—a feeling which overwhelms and suspends the human capacity to imagine

and understand, is a distinctly in-human aesthetic category. As such, Lyotard’s

various engagements with artists and aesthetics can be understood as philosophical

experiments with this analogy of the inhuman and the sublime. It is clear that

Lyotard’s work provides several resources that contribute to what is termed

‘posthuman studies’, despite the underuse of Lyotard as a point of reference in

this field, as will be argued below. Through a review of literature and Les

Immatériaux, this essay will explore the extent of these resources and

their relevance to art theoretical discourse that is set on renegotiating the

limits and purview of humanism today.

Across Lyotard’s engagements with art, there is a sustained reference to the avant-garde: to specific artists and as a concept in general. The Postmodern Condition observes that the avant-garde signs a contradiction that, at once, demands for a suspension of ‘artistic experimentation’, coupled with ‘an identical call for order, a desire of unity, for identity, for security, or popularity’.1 In other words, under the banner of postmodernism, the notion of an avant-garde artistic community is both embraced and condemned for being without purposeful and/or recognisable reference. Lyotard posits that postmodern art does not affirm earlier standards of realism, often to the point of collapse to kitsch, where ‘art panders to the confusion which reigns in the “taste” of the patrons’.2 Kitsch is postmodern nihilism of taste at its zenith, subverting the conventional pillars of what is beautiful toward an ‘aesthetic of the sublime that modern art (including literature) finds its impetus and the logic of the avant-gardes finds its axiom’.3 The aesthetic category of the sublime—derived by Lyotard from Kant’s third critique—comes to define the character of avant-garde artistic communities, and offers an appeal to enact and witness modernity’s undoing. It is an eminently artistic strategy that ‘allows the unpresentable to be put forward as the missing contents, but the form, because of its recognisable consistency, continues to offer to the reader or viewer matter for solace and pleasure’.4 To make sense of this contradiction, Lyotard invokes the paradoxical sentiment of post modo—or the future anterior—to explain the sublime feeling conjured by postmodern art as a shock to subjectivity by once-familiar means at a time; a confrontation to the viewer that makes themselves accountable and immanent to contents, themes and materials preceding and exceeding modernity.

Following from this point it is suitable to note how Lyotard’s philosophy is consistent in his effort to emphasise the status of nihilism in modernity, and how nihilism is an irreducible component of capitalism, technological industry, and of the production of knowledge in imperialist institutions in general. In an early essay titled “Dead Letter”, Lyotard draws out the contemporary nihilist separation of existence and meaning, which impoverishes culture (the union of these two terms in Lyotard’s formulation). Invoking the familiar Marxist theme of alienation via mechanisation, Lyotard rhetorically asks ‘what meaning is there in existing?’: ‘a question that resounds for everyone, Monday morning and Saturday night, that reveals the emptiness of “civilization” in all its industrial flashiness’.5 Our daily labour and leisure is devoid of meaning when it is ‘organised by the model of the machine, a model whose purpose lies outside itself, which does not question that purpose’.6 To embrace this void is to reduce down to ‘a technologism that seeks its reason in itself alone’, thereby dividing meaning and existence, denigrating culture and succumbing to bureaucratic and recursive lifestyles without purpose. “Dead Letter” is reflective of Lyotard’s early anti-capitalism sentiment, which would persist despite his developing critical distance from his conventional Marxist peers. However, from 1980 onwards (marked by the publication of The Differend), the nature of Lyotard’s anti-capitalism—in particular its anti-technological sensibilities—would start to shift and complicate, particularly as he began to pay closer attention to aesthetic experience, the avant-garde and the sublime.

Ashley Woodward thematises Lyotard’s writing from 1980 onward as having frequent recourses ‘to the aesthetic of the sublime… which has traditionally been invoked to explain the experience of things which move us, but cannot be explained according to the traditional theories of the beautiful’.7 Despite inconsistencies in how Lyotard presents his analysis of the sublime, Woodward notes that ‘the sublime typically appears with a positive valence in his work, and is posited as offering creative possibilities beyond the impasses of modern thought and the postmodern social conditions’.8 In 1991 Lyotard published his Lessons on the Analytic of the Sublime, which is a direct reading of the concept of the sublime as presented by Kant’s third critique, and the place that it has occupied in Lyotard’s own philosophical project. ‘Sublime feeling’ is characterised here as having ‘neither moral universality nor aesthetic universalisation, but is, rather, the destruction of the one by the other in the violence of their differend’.9 In other words, a sublime feeling has the capacity to annihilate, to void once immutable relations and fundamental constructs, categories and concepts.