Questioning the Mirror: Re-Imagining the

Southeast Asian Female Archetype through Performative Video

Lizzie Wee

To cite this contribution:

Mildred Wee, Elizabeth. ‘Questioning the Mirror: Re-Imagining the

Southeast Asian Female Archetype through Performative Video’. Currents Journal, Archipelagic Encounters (2021), https://currentsjournal.net/Questioning-the-Mirror

Download this article ︎︎︎PDF

Keywords: archetypes, performance, performative video, mirror, belonging, autoethnographic, phenomenological, process, mapping, home, question, self-reflection, identity, acceptance.

Abstract: This article expands on artist Lizzie Wee’s practice-based research which investigates the concept of belonging as a means of understanding how one ‘belongs’ in a given place when one is unsure about identity and unable to define ‘home’. Instead of asking where does one belong, her research proposes the question: how could one belong? Looking at Homecoming/The Lee Family (2020) and Forced Idleness (2021) more closely, Wee examines how her process of mapping archetypes and performing to the camera can lead to relating to other young Southeast Asian women. The medium of performative video is thus shown to be a way of understanding belonging, through self-reflection and demonstration. By using a combination of various autoethnographic and phenomenological methods, such as surveying, watching, reflecting, writing, performing, and editing, Wee attempts to devise a working model or systematic process to work creatively through uncertainty about identity. This is exemplified in her final works for her MA, Homecoming - The Table Read (2021) and Homecoming - The Conversations (2021), two video pieces that cycle and give greater context to each other, which allowed Wee to question the mirror whether she is looking for belonging or acceptance from others or ultimately, from herself.

Lizzie Wee, video still, Forced Idleness (2021) Single-channel digital video, 16:9 format, 5m 40s (https://vimeo.com/515150950)

Lizzie Wee, video still, Forced Idleness (2021) Single-channel digital video, 16:9 format, 5m 40s (https://vimeo.com/515150950)

Homecoming/The Lee Family (2020) Single-channel digital video, 16:9 format, 14m 49s (https://vimeo.com/512420286)

Forced Idleness (2021) Single-channel digital video, 16:9 format, 5m 40s (https://vimeo.com/515150950)

Forced Idleness (2021) Single-channel digital video, 16:9 format, 5m 40s (https://vimeo.com/515150950)

Homecoming - The Table Read (2021), Single-channel 4K digital video, 16:9 format, 26m 54s

(https://vimeo.com/543957247).

Homecoming - The Conversations (2021), Single-channel 4K digital video, 16:9 format, 32m 18s. (https://vimeo.com/542018102)

Homecoming/The Lee Family (2020) is a performative video

work, which shows the cast and crew of an original, imagined, and unmade

television show participating in a virtual table read. Forced Idleness (2021) is a performative video sketch, showing the

cast of Homecoming, the aforementioned

show, detailing their lives in lockdown. All roles are performed by me, the

artist; creating a mirroring that

speaks to my own act of self-reflection and roleplay in search of belonging and

identity. Drawing from my own lived experiences as a Southeast Asian woman who

has lived in many cities including Kuala Lumpur, Hong Kong, Berlin, Boston, New

York, and Singapore, the work addresses the desire to ‘place’ oneself in spite

of the displacement one feels when cultures collide.

Both works are a part of my ongoing practice-led research into the process of locating and performing identity and belonging. The works deal with the notion of ‘performance’ through two layered frames: Firstly, through the narrative frame of an imagined television show that adapts original but recognisable archetypes and places them in mock reality scenarios. Secondly, through the visual language of an online conference call, which has, over the duration of the pandemic, become a universally familiar platform. The format of the online conference call is employed to examine the disruptions to ‘normality’ we have experienced during the pandemic, and creates a space where fictions and realities can be staged, performed and questioned. These performative video works utilise humour to draw audiences into the fictions that I have created in an attempt to re-shape our perceptions of reality and blur the boundaries of what roles Southeast Asian women, including myself, are expected to look to and perform. As a whole, the two works serve as my own embodied examination of ‘belonging’, which begins with replicating archetypes and subsequently questioning and subverting the dominance of their presence on screen.

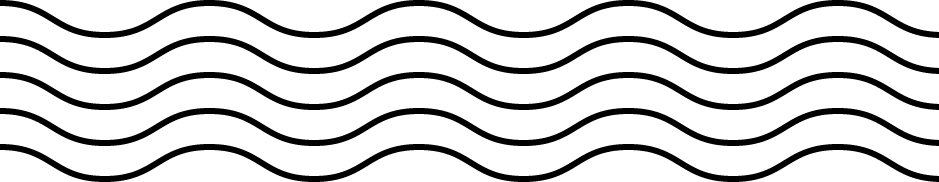

The methodology for this practice-led project comprises four parts: First, a survey of selected popular Southeast Asian film and television programmes, using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA)1 to describe and categorise the types of female characters that would appear. Second, I reviewed these categories to construct a ‘map’ [Figure 1] of these archetypes and how they might relate to each other, as well as to re-imagine and re-write these archetypes into specific characters with an entirely original narrative that I could embody and perform for the camera. I drew from Phua Chu Kang Pte. Ltd., a locally-produced Singaporean television sitcom,2 and reoriented the narrative and a few of the main female characters through my writing and performance, resulting in Homecoming. Third, I experimented with drawing out the narrative arcs and relationships of each of my characters through both script-writing and improvised line readings to the camera. Four, I collated and edited my performances into short videos that I would further reflect on and analyse.

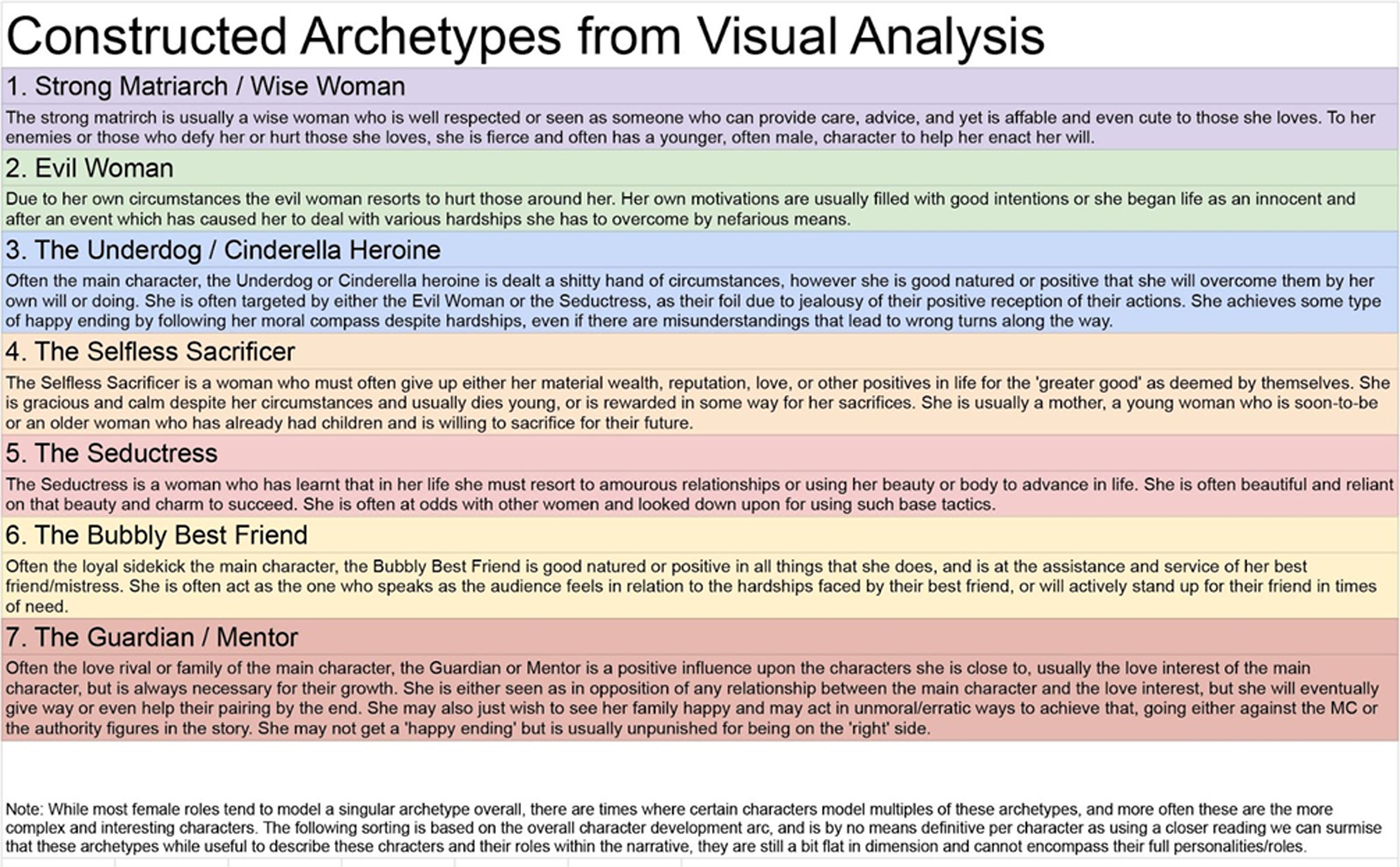

Reflecting on the work done so far, I have found that while constructing archetypes informed my writing and performance, they also highlighted a key conflict between fiction and reality or more specifically, between my own lived experiences as well as that of other Southeast Asian women and how we are then represented on screen. Idealised characters may provide an ‘easy’ and accessible path towards understanding motivations and challenges, but they also inflict expectations upon ‘real women’ of Southeast Asia, including myself. Archetypes may refer to flattened patterns or models of which all things of the same type are representations or copies.3 In my own view, my constructed archetypes are a distillation of the similarities between many female characters and their roles as women within their various narratives, despite their diversity and multiplicities. Identifying specific archetypes while learning about local pop culture was a means for me to examine established and well-loved stories in order to figure out my own role or place. Although I related to the women I saw on screen, I still felt somewhat disconnected, and so rather than simply appropriating the source material, I wished to use a more layered approach to, in the words of Judith Butler, ‘give an account of myself, [to make myself] recognizable and understandable, [I might] begin with a narrative account of my life, but this narrative will be disoriented by what is not mine, or what is not mine alone.’4 These archetypes were formulated based on my interpretation of the represented women I saw on screen, a distillation of a particular fiction rather than a whole picture of the complex and nuanced realities of Southeast Asian women. This lens of personal interpretation was important in my processes of mirroring and mapping [Figure 2].

![]()

[Figure 1] Constructed Archetypes from Wee’s visual analysis conducted in 2020-21.

![]()

[Figure 2] Elizabeth Mildred Wee, excerpt from visual analysis of Thailand television characters conducted in 2020-21.

Searching for belonging is an intangible and slippery quest. With my practice, I seek to move beyond ‘home’ as a location and to untie ‘belonging’ from a specific place. Instead, I focus on the processes in which we seek acceptance and comfort within ourselves. Rather than asking ‘where do I belong?’, I am much more interested in asking ‘how do I belong?’. The intersection of writing, performing and producing video work allowed me to use the camera as a mirror and create performative videos, synthesised from an original narrative with female characters for performance. By embodying these roles as distinct characters in a specific narrative, anchored in Singapore, I hope to see how I might create the necessary critical distance from my own image and performance, to better see myself and thus, clarify and understand how to belong. My return to Singapore to pursue this topic has coloured my research into Southeast Asian female archetypal roles, with the greater context of a physical homecoming; it has paralleled my practice, with a struggle to find my place within a city I have not called home since birth. I will continue to use these original characters and narratives as a framework to investigate belonging through performance, and to see where these fictions border reality.

I see my process of watching, reflecting, writing, and finally performing female characters as a model and method for working through my uncertainty about identity; rather than only watching or consuming media one relates to, one should create, write, and use performance to work through it. My work often has a sense of ambiguity due to the unfinished aspect or allusion that the characters are still in the midst of working towards the end of an ongoing project, which is intentional; I hope to convey that, like my characters, I am also unfinished, but in a state of progress. The medium of performative video is my way of understanding belonging, through self-reflection and demonstration. At first glance, one can see the work as simply amusement and enjoy it at face value, but I see the humour as a vehicle which points to many harder topics of conversation and the subsequent healing needed. This duality between pain and enjoyment hints at desire, perhaps my own, for acceptance and belonging, but whether I seek it from a community or from myself is still unclear. By situating myself in a broader context and generalising my research beyond my own story, I aim to better relate my experiences to a wider audience, and eventually shatter the mirrors or expectations of those archetypal roles for myself and other young Southeast Asian women.

Notes:

1. Andrews, Jorella. “Interviewing Images: How Visual Research Using IPA (Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis) Can Illuminate the Change-Making Possibilities of PLACE, Space, and Dwelling.” Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Dwelling Form (IDWELL 2020), vol. 475, 2020, pp. 20–31., doi:10.2991/assehr.k.201009.003.

2. Mediacorp, ‘Phua Chu Kang Pte Ltd S1 Show Info’, MeWatch, tv.mewatch.sg/en/shows/p/phua-chu-kang-pte-ltd-s1/info.

3. Archetype, Merriam-Webster Dictionary Website, www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/archetype.

4. Judith Butler, ‘Giving an Account of Oneself’. Diacritics, vol. 31, no. 4 (2001): 26.

About the contributor: Lizzie Wee is a Singaporean multidisciplinary artist, designer, illustrator, art director and video editor. She has lived in many cities including Kuala Lumpur, Hong Kong, Berlin, Boston, New York, and Singapore. She received her BFA from New York University and an MA Fine Arts from the Goldsmiths programme at LASALLE College of the Arts. Her present practice-based research investigates notions of identity and belonging; through an examination of archetypal female roles found in Southeast Asian pop culture and visual media. Her works are expressed through video, performance, writing for performance, and multimedia installation. She has exhibited her work in various international galleries, showcases, symposiums, and art fairs online and in Singapore, Taiwan, Shenzhen, Szczecin, New York, and Shanghai. Apart from her artistic practice, Wee has worked with Sotheby's Hong Kong, and Kitchen Hoarder, a woman-run production team focused on lifestyle and food culture.

Both works are a part of my ongoing practice-led research into the process of locating and performing identity and belonging. The works deal with the notion of ‘performance’ through two layered frames: Firstly, through the narrative frame of an imagined television show that adapts original but recognisable archetypes and places them in mock reality scenarios. Secondly, through the visual language of an online conference call, which has, over the duration of the pandemic, become a universally familiar platform. The format of the online conference call is employed to examine the disruptions to ‘normality’ we have experienced during the pandemic, and creates a space where fictions and realities can be staged, performed and questioned. These performative video works utilise humour to draw audiences into the fictions that I have created in an attempt to re-shape our perceptions of reality and blur the boundaries of what roles Southeast Asian women, including myself, are expected to look to and perform. As a whole, the two works serve as my own embodied examination of ‘belonging’, which begins with replicating archetypes and subsequently questioning and subverting the dominance of their presence on screen.

The methodology for this practice-led project comprises four parts: First, a survey of selected popular Southeast Asian film and television programmes, using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA)1 to describe and categorise the types of female characters that would appear. Second, I reviewed these categories to construct a ‘map’ [Figure 1] of these archetypes and how they might relate to each other, as well as to re-imagine and re-write these archetypes into specific characters with an entirely original narrative that I could embody and perform for the camera. I drew from Phua Chu Kang Pte. Ltd., a locally-produced Singaporean television sitcom,2 and reoriented the narrative and a few of the main female characters through my writing and performance, resulting in Homecoming. Third, I experimented with drawing out the narrative arcs and relationships of each of my characters through both script-writing and improvised line readings to the camera. Four, I collated and edited my performances into short videos that I would further reflect on and analyse.

Reflecting on the work done so far, I have found that while constructing archetypes informed my writing and performance, they also highlighted a key conflict between fiction and reality or more specifically, between my own lived experiences as well as that of other Southeast Asian women and how we are then represented on screen. Idealised characters may provide an ‘easy’ and accessible path towards understanding motivations and challenges, but they also inflict expectations upon ‘real women’ of Southeast Asia, including myself. Archetypes may refer to flattened patterns or models of which all things of the same type are representations or copies.3 In my own view, my constructed archetypes are a distillation of the similarities between many female characters and their roles as women within their various narratives, despite their diversity and multiplicities. Identifying specific archetypes while learning about local pop culture was a means for me to examine established and well-loved stories in order to figure out my own role or place. Although I related to the women I saw on screen, I still felt somewhat disconnected, and so rather than simply appropriating the source material, I wished to use a more layered approach to, in the words of Judith Butler, ‘give an account of myself, [to make myself] recognizable and understandable, [I might] begin with a narrative account of my life, but this narrative will be disoriented by what is not mine, or what is not mine alone.’4 These archetypes were formulated based on my interpretation of the represented women I saw on screen, a distillation of a particular fiction rather than a whole picture of the complex and nuanced realities of Southeast Asian women. This lens of personal interpretation was important in my processes of mirroring and mapping [Figure 2].

[Figure 1] Constructed Archetypes from Wee’s visual analysis conducted in 2020-21.

[Figure 2] Elizabeth Mildred Wee, excerpt from visual analysis of Thailand television characters conducted in 2020-21.

Searching for belonging is an intangible and slippery quest. With my practice, I seek to move beyond ‘home’ as a location and to untie ‘belonging’ from a specific place. Instead, I focus on the processes in which we seek acceptance and comfort within ourselves. Rather than asking ‘where do I belong?’, I am much more interested in asking ‘how do I belong?’. The intersection of writing, performing and producing video work allowed me to use the camera as a mirror and create performative videos, synthesised from an original narrative with female characters for performance. By embodying these roles as distinct characters in a specific narrative, anchored in Singapore, I hope to see how I might create the necessary critical distance from my own image and performance, to better see myself and thus, clarify and understand how to belong. My return to Singapore to pursue this topic has coloured my research into Southeast Asian female archetypal roles, with the greater context of a physical homecoming; it has paralleled my practice, with a struggle to find my place within a city I have not called home since birth. I will continue to use these original characters and narratives as a framework to investigate belonging through performance, and to see where these fictions border reality.

I see my process of watching, reflecting, writing, and finally performing female characters as a model and method for working through my uncertainty about identity; rather than only watching or consuming media one relates to, one should create, write, and use performance to work through it. My work often has a sense of ambiguity due to the unfinished aspect or allusion that the characters are still in the midst of working towards the end of an ongoing project, which is intentional; I hope to convey that, like my characters, I am also unfinished, but in a state of progress. The medium of performative video is my way of understanding belonging, through self-reflection and demonstration. At first glance, one can see the work as simply amusement and enjoy it at face value, but I see the humour as a vehicle which points to many harder topics of conversation and the subsequent healing needed. This duality between pain and enjoyment hints at desire, perhaps my own, for acceptance and belonging, but whether I seek it from a community or from myself is still unclear. By situating myself in a broader context and generalising my research beyond my own story, I aim to better relate my experiences to a wider audience, and eventually shatter the mirrors or expectations of those archetypal roles for myself and other young Southeast Asian women.

Notes:

1. Andrews, Jorella. “Interviewing Images: How Visual Research Using IPA (Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis) Can Illuminate the Change-Making Possibilities of PLACE, Space, and Dwelling.” Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Dwelling Form (IDWELL 2020), vol. 475, 2020, pp. 20–31., doi:10.2991/assehr.k.201009.003.

2. Mediacorp, ‘Phua Chu Kang Pte Ltd S1 Show Info’, MeWatch, tv.mewatch.sg/en/shows/p/phua-chu-kang-pte-ltd-s1/info.

3. Archetype, Merriam-Webster Dictionary Website, www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/archetype.

4. Judith Butler, ‘Giving an Account of Oneself’. Diacritics, vol. 31, no. 4 (2001): 26.

About the contributor: Lizzie Wee is a Singaporean multidisciplinary artist, designer, illustrator, art director and video editor. She has lived in many cities including Kuala Lumpur, Hong Kong, Berlin, Boston, New York, and Singapore. She received her BFA from New York University and an MA Fine Arts from the Goldsmiths programme at LASALLE College of the Arts. Her present practice-based research investigates notions of identity and belonging; through an examination of archetypal female roles found in Southeast Asian pop culture and visual media. Her works are expressed through video, performance, writing for performance, and multimedia installation. She has exhibited her work in various international galleries, showcases, symposiums, and art fairs online and in Singapore, Taiwan, Shenzhen, Szczecin, New York, and Shanghai. Apart from her artistic practice, Wee has worked with Sotheby's Hong Kong, and Kitchen Hoarder, a woman-run production team focused on lifestyle and food culture.

Currents is a collaboration between the Centre of Visual Art (CoVA) at the University of Melbourne and the School of Design, University of Western Australia, and is funded through the Schenberg International Arts Collaboration Program. The Advisory Board and Editorial Committee are comprised of staff and graduate students from across the University of Melbourne and the University of Western Australia.

Currents acknowledges the traditional owners and ongoing custodians of the land on which this journal is produced—the Boonwurung and Wurundjeri people of the Eastern Kulin Nation and Whadjuk people. We pay our respects to land, ancestors and Elders, and know that education involves working with their guidance to improve the lives of all.

ISSN 2652-8207

![]()

![]()

Currents acknowledges the traditional owners and ongoing custodians of the land on which this journal is produced—the Boonwurung and Wurundjeri people of the Eastern Kulin Nation and Whadjuk people. We pay our respects to land, ancestors and Elders, and know that education involves working with their guidance to improve the lives of all.

ISSN 2652-8207