Shaping Perception: Negotiating media as material, the fragility of time and fleeting emotions

Zoya Chaudhary

To cite this contribution: Chaudhary, Zoya. ‘Shaping Perception: Negotiating media as material, the fragility of time and fleeting emotions’. Currents Journal, Archipelagic Encounters (2021), https://currentsjournal.net/Shaping-Perception.

Download this article ︎︎︎PDF

Keywords: Jali, materiality, media, erasure, newspaper

Abstract:The essay, artwork and process imagery presented here, features hand cut-out newspaper works from my (Zoya Chaudhary) series Fragments & Echo that draw inspiration from Indo-Persian latticed Jali. The series negotiates news media reportage and materiality as a testament to the fragility of time, space and fleeting emotional responses. By cutting, burning and scratching patterned motifs into the surface of newspapers from particular dates, I explore the notion of ‘media as material’. This is to consider news media as a referent to past events that are under erasure in their representational form, drawing attention to their materiality.

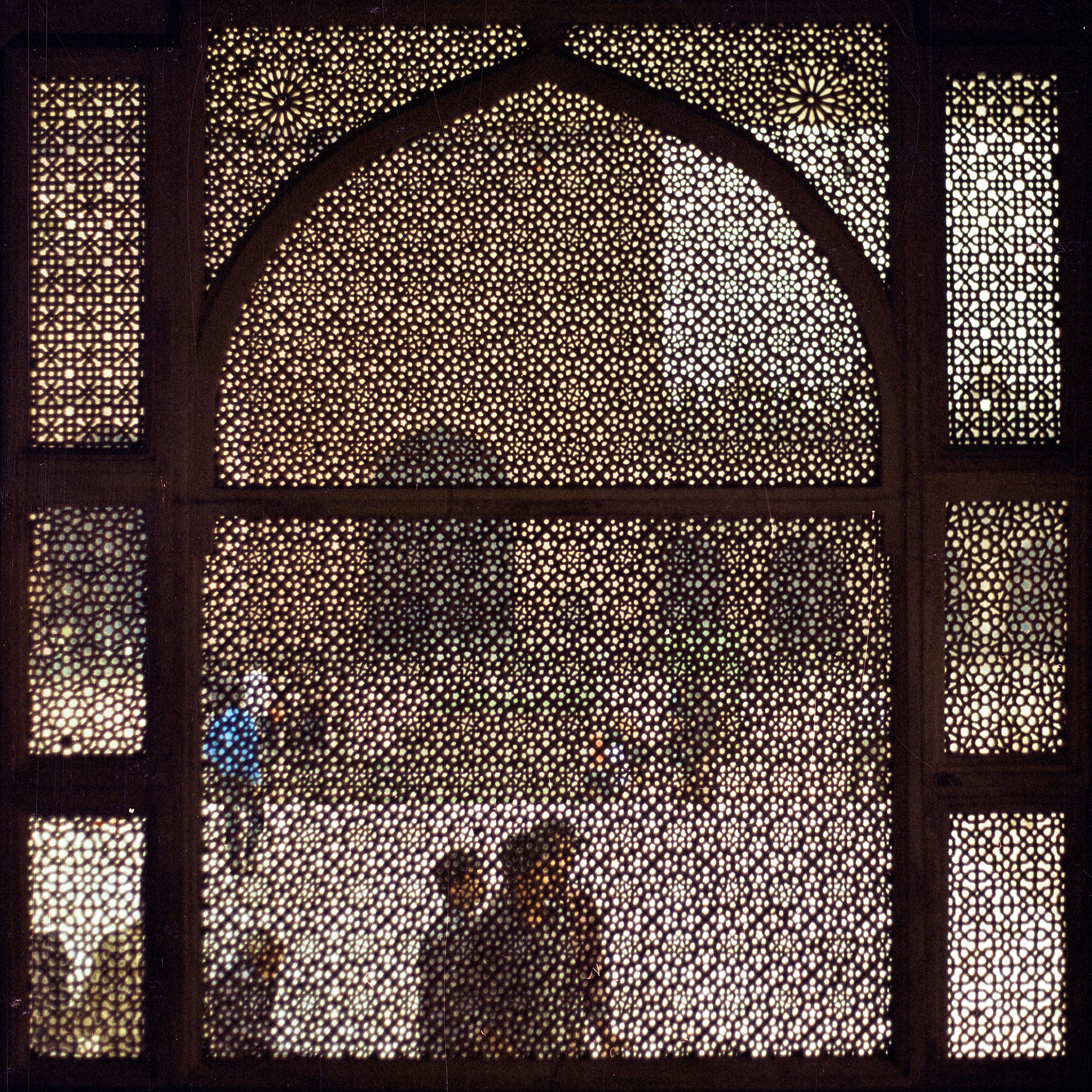

[Figure 1] Reference image of Jali marble carved windows from Fatehpur Sikri, India. https://www.flickr.com/photos/doctorcasino/7809341254/. Accessed 26th September 2021. Courtesy Addison Godel.

The dull white The Straits Times newspaper from May 15, 2021 that I had glued onto a thin canvas sheet had darkened and wrinkled in some places. I scratched and sanded the newspaper surface to even it out. I cut patterns by following lines I had previously traced on the glued newspaper. ‘Rare fungal infection hits COVID-19 patients in India’—a line I had read and cutover, kept ringing in my head alongside an image of two men, one of them unmasked, carrying another man into a rural looking clinic. I can not remember if the image was from the same article or was from another article on the same page, yet the image and text are vaguely connected in my memory. Residing in Singapore, I have not been able to visit my home country, India, since January 2020. My 92-year-old grandfather had just recovered from the COVID-19 virus and was back home from hospital, thankfully, I thought. But the lingering dread around the implications of the new ‘black fungus’ infection stayed. At least it stayed until the sound of water coming to full boil in the water heater distracted my thoughts. Sipping my coffee, I was back to rhythmic cutting, calm again as I cut, cut, and cut. At the corner where I had cut out a shape, a tiny little piece of the newspaper peeled out. Images, thoughts, and surrounding sounds seemed to have merged, forming a blur in my head.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Images

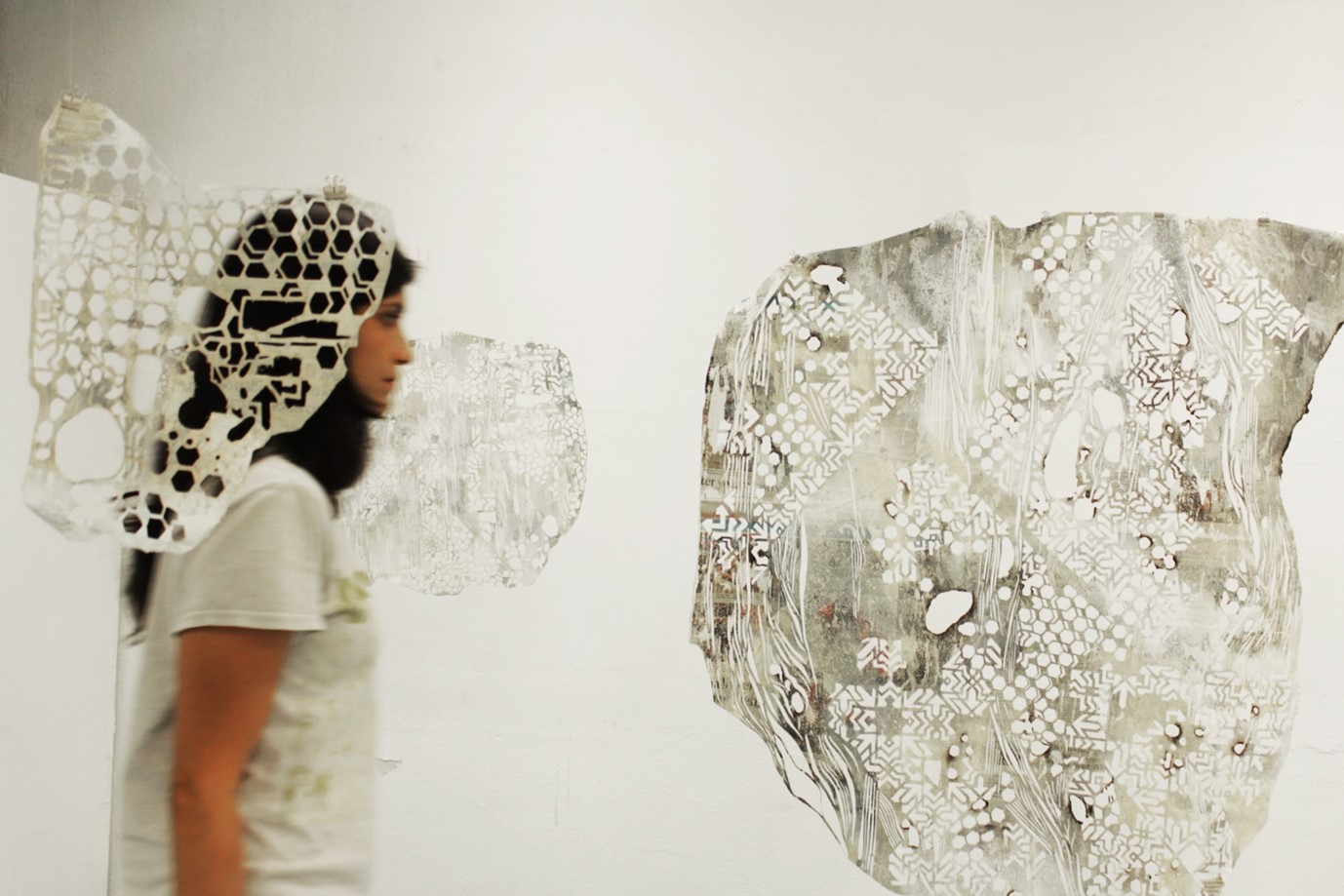

^^^

From

March18..., 2020, series ‘Fragments’ as displayed at Lasalle

Winstedt studio space, Singapore. Image

of the series ‘Echo’, as displayed at Lasalle Winstedt studio space, Singapore, 2020.

Close-up of overlapping surfaces

from the series Echo, 2020

Images

^^^

From

March18..., 2020, series ‘Fragments’ as displayed at Lasalle

Winstedt studio space, Singapore. Image

of the series ‘Echo’, as displayed at Lasalle Winstedt studio space, Singapore, 2020.

Close-up of overlapping surfaces

from the series Echo, 2020

Media in its various formats is perhaps the most ubiquitous and powerful force that is shaping perception and memory in current times. My practice-based research is focused on the formation of subjectivity and perception in relation to the information gleaned from media. Especially how subjective filters of perception are created from the cultural, physical, and temporal vantage point affected by notions of erasure. In this essay, I will discuss works from my series Fragments & Echo, works that I started making from March 2020 onwards. I was then in the first semester of my Master of Fine Arts degree at LASALLE College of Arts, Singapore, which also coincided with the break-out of the pandemic. In the following text, I will first discuss the cut-out mesh-like surfaces that I create and the historical and cultural significance of the Jali [Figure 1] inspired patterns in my works. I will then expand on the use of media, specifically the daily newspaper—as a representational form that communicates events on the one hand and the materiality of its surface on the other. I hope to be able to draw connections between the fragility of the material outcome of the works, which is a testament to the fragile interrelations of time, space, and fleeting emotions. Burning

The cut-out surfaces

I view my works from the series Fragments & Echo presented here as one of the many layers of filters that holds a trace or fragmented memories of a time and space. The traces of newsprint on the cut-out patterned surfaces in Fragments & Echo suggests a residual fragmented memory comprised of lost information and a perceptual shift between media and material. Formally these cut-out surfaces seek to open a space for the viewer to explore their own perceptual awareness of unique spatial and temporal conditions. Cut-out surfaces in my works act like filters of perception. The porosity of the surfaces is tied to John Berger’s idea evoked above, speaking to the enormous ‘gap’ between the narrative being offered to us through various apparatus, such as newspapers, and our experience of an internal ever-changing subjectivity. Each individual has built-in psychological filters that we use to focus or block out external information that are perceived and received in diverse ways. Exploring my personal filters, I drew inspiration from Jali patterns to cut-out geometric shapes that have a cultural significance for me.

Jali as a personal frame

Indo-Persian latticed Jali screens, an architectural feature, are patterned carvings of stone railings and screens that are found in older homes, temples, mosques, and monuments across the Indian subcontinent. The word Jali meaning ‘an iron net’ in Urdu and Sanskrit is employed to describe pierced screens.2 Historically, in Asia and the Mediterranean where the sun rays can be very strong, master artisans evolved this aesthetic language of light. In India, these perforated screens have been traced back to the mid-sixth century Chalukyan period.3 The carved-out lattice patterns on stone and other material shaped and filtered light into enclosed spaces lending a luminescent softness and providing a cooling effect. The Islamic influence brought in complex patterns built on tessellation, a simple geometric progression of a single form that was representative of the infinite nature of the divine. Living in Singapore, away from my home country, the Jali patterned surfaces conceptually and materially act as a cultural framing device. Personally, for me, these walls are nostalgic and remind me of places and experiences of my childhood. The craft of Jali within the Indian sub-continent can be traced to an origin that combines Hindu craftsmen’s indigenous skills with Islamic geometric designs.4 The lineage of Jali designs is pertinent to my relationship with the Jali and why I use it as a reference in my practice, as I come from a mixed Hindu and Muslim parentage. This unique cultural union, which is rare between people, even in present-day India due to religious polarisation, is visible in the architecture, food, poetry, and many other aspects of Indian cultural heritage including the Jali, hence making it a strong starting point for me.

![]() Image

^^^

Close up images of the making of From April10..., 2020, series ‘Fragments’.

Image

^^^

Close up images of the making of From April10..., 2020, series ‘Fragments’.

Media as a material trace

In this accompanying text, I will discuss the notion of ‘media as a material’ and how this idea functions within my series Fragments & Echo. My practice to date has led me to look at news media as a referent to past events but also how it has been materially presented. Jacques Derrida's writings on language as a ‘trace’ informed my way of looking at media as a material trace. Derrida refers to the trace as a ‘still-living mark on the substrate, a surface, a place of origin’.5 By referring to language as ‘trace’ instead of a sign, Derrida acknowledges the limitation of the written ‘word’, suggesting that it is neither present nor absent. Charles Merewether in his essay Fact Remains uses Derrida’s notion of ‘trace’ and applies it to photographic and video representations of events. He questions the acceptance of such representation as material evidence and calls it ‘trace’ to critique its dependability. Merewether explains,

This aspect, of a trace being neither past nor present, is particularly relevant to the subject of media information that is presented as truth. Merewether further argues that ‘[i]n allowing us to look back, the trace offers a connection to the world insofar as it operates as a memorial form tied to the past but, forever threatened by forgetfulness and erasure.’7

Media in its various formats is perhaps the most ubiquitous and powerful force that is shaping perception and memory in current times. My practice-based research is focused on the formation of subjectivity and perception in relation to the information gleaned from media. Especially how subjective filters of perception are created from the cultural, physical, and temporal vantage point affected by notions of erasure. In this essay, I will discuss works from my series Fragments & Echo, works that I started making from March 2020 onwards. I was then in the first semester of my Master of Fine Arts degree at LASALLE College of Arts, Singapore, which also coincided with the break-out of the pandemic. In the following text, I will first discuss the cut-out mesh-like surfaces that I create and the historical and cultural significance of the Jali [Figure 1] inspired patterns in my works. I will then expand on the use of media, specifically the daily newspaper—as a representational form that communicates events on the one hand and the materiality of its surface on the other. I hope to be able to draw connections between the fragility of the material outcome of the works, which is a testament to the fragile interrelations of time, space, and fleeting emotions. Burning

The cut-out surfaces

Between the experience of living a normal life at this moment on the planet and the public narratives being offered to give a sense of that life, the empty space, the gap, is enormous.1

-John Berger

I view my works from the series Fragments & Echo presented here as one of the many layers of filters that holds a trace or fragmented memories of a time and space. The traces of newsprint on the cut-out patterned surfaces in Fragments & Echo suggests a residual fragmented memory comprised of lost information and a perceptual shift between media and material. Formally these cut-out surfaces seek to open a space for the viewer to explore their own perceptual awareness of unique spatial and temporal conditions. Cut-out surfaces in my works act like filters of perception. The porosity of the surfaces is tied to John Berger’s idea evoked above, speaking to the enormous ‘gap’ between the narrative being offered to us through various apparatus, such as newspapers, and our experience of an internal ever-changing subjectivity. Each individual has built-in psychological filters that we use to focus or block out external information that are perceived and received in diverse ways. Exploring my personal filters, I drew inspiration from Jali patterns to cut-out geometric shapes that have a cultural significance for me.

Jali as a personal frame

Indo-Persian latticed Jali screens, an architectural feature, are patterned carvings of stone railings and screens that are found in older homes, temples, mosques, and monuments across the Indian subcontinent. The word Jali meaning ‘an iron net’ in Urdu and Sanskrit is employed to describe pierced screens.2 Historically, in Asia and the Mediterranean where the sun rays can be very strong, master artisans evolved this aesthetic language of light. In India, these perforated screens have been traced back to the mid-sixth century Chalukyan period.3 The carved-out lattice patterns on stone and other material shaped and filtered light into enclosed spaces lending a luminescent softness and providing a cooling effect. The Islamic influence brought in complex patterns built on tessellation, a simple geometric progression of a single form that was representative of the infinite nature of the divine. Living in Singapore, away from my home country, the Jali patterned surfaces conceptually and materially act as a cultural framing device. Personally, for me, these walls are nostalgic and remind me of places and experiences of my childhood. The craft of Jali within the Indian sub-continent can be traced to an origin that combines Hindu craftsmen’s indigenous skills with Islamic geometric designs.4 The lineage of Jali designs is pertinent to my relationship with the Jali and why I use it as a reference in my practice, as I come from a mixed Hindu and Muslim parentage. This unique cultural union, which is rare between people, even in present-day India due to religious polarisation, is visible in the architecture, food, poetry, and many other aspects of Indian cultural heritage including the Jali, hence making it a strong starting point for me.

Image

^^^

Close up images of the making of From April10..., 2020, series ‘Fragments’.

Image

^^^

Close up images of the making of From April10..., 2020, series ‘Fragments’.Media as a material trace

In this accompanying text, I will discuss the notion of ‘media as a material’ and how this idea functions within my series Fragments & Echo. My practice to date has led me to look at news media as a referent to past events but also how it has been materially presented. Jacques Derrida's writings on language as a ‘trace’ informed my way of looking at media as a material trace. Derrida refers to the trace as a ‘still-living mark on the substrate, a surface, a place of origin’.5 By referring to language as ‘trace’ instead of a sign, Derrida acknowledges the limitation of the written ‘word’, suggesting that it is neither present nor absent. Charles Merewether in his essay Fact Remains uses Derrida’s notion of ‘trace’ and applies it to photographic and video representations of events. He questions the acceptance of such representation as material evidence and calls it ‘trace’ to critique its dependability. Merewether explains,

‘… to view the event in such terms (material evidence) is to suggest that a material memory or trace to do with the past survives in the present, a materiality that can be identified. Is the trace therefore something residual: a remainder that survives, like a fragment? Or is the trace alternatively, something less, insofar as its appearance is not a matter of survival but, rather more like the hollowed-out imprint of an impression: a past that has never been present?’6

This aspect, of a trace being neither past nor present, is particularly relevant to the subject of media information that is presented as truth. Merewether further argues that ‘[i]n allowing us to look back, the trace offers a connection to the world insofar as it operates as a memorial form tied to the past but, forever threatened by forgetfulness and erasure.’7

This vulnerable presence of the trace of news media in material form is

very powerful to me since it directly critiques the idea of truth. In these

works, I aim to create a tension caused by the presence of the newspaper referring to the conditions of time in residual remains on the one hand, and the delicately cut-out material, on the other. How a news article, a representation of an event in the form of pictures

and words is materially presented relates directly to their social, economic,

political discourse and how it’s received and handled relates to the personal. The text, made unreadable or incoherent, suggests a

'distance', which could refer to the disappearance or fading away of the trauma

of news events. The tools and

actions that I have chosen to use to interact with the ‘media-material’ become

important, as they reflect my underlying motivations, intentions, and emotional

reactions to the particularities of the media material. I take the media material

and with the help of either physical or digital tools, edit the material by

scratching, cutting, burning, erasing, or blurring almost wrestling with it to transform

it into something delicate and almost beautiful.

Fragments & Echo

In the series of works called Fragments & Echo, I started with gluing sheets of newsprint paper on canvas. I then indeterminately scratched out portions of the surface. I had been occupied with the idea of filters (both perceptual and conceptual) and the correlation with screens as a type of filter or viewing device. The idea of the artwork taking on the characteristics of a filter seemed exciting. I started using repetitive shapes forming Jali-inspired patterns to cut-out sections from a sheet of newspaper stuck to a thin canvas, transforming into a mesh-like form. During this process I was trying to better understand the subjective filters I apply when viewing the mediated public narrative that is given to us through media. I thought about the juxtaposition of the rhythmic patterns of my presence, my breath, my daily routines with the media information I was working with. To visually present this feeling I traced a combination of two or three existing Jali pattern designs from architectural Jali drawings. Combining repetitive patterns, some determinate, some indeterminate, I would cut over the traced lines on the surface. The neatness of the cut-out forms varied with the state of mind I was in. By cutting the geometric forms and burning holes with incense sticks and a kitchen lighter, I transformed the surface into a mesh-like form. I started work on the first Jali work From March 18… from the series Fragments & Echo, around the time Singapore was in its lockdown due to the onset of the global COVID-19 pandemic. The local newspaper at that point was filled with virus-related news that depicted the anxiety and panic that could be felt across the globe. Taking newsprint paper from a single day, I used household tools to create a surface with suggestions of the news but transformed it into something that was not very definitive and open to interpretation. While cutting out patterns, I would get carried away by the repetitive actions, at times forgetting what I was cutting. The forms, images, and text became abstract material that I was shaping. But at other times I would stop and read or re-read the news article and take in the information. Sometimes, I would avoid cutting out an immigrant child's face, at other times I would want to cut-out a certain news piece with a statistical chart of a certain country’s virus death toll, rendering it invisible. News about jobless migrant workers from poor neighbouring countries desperate to get out of Thailand out of fear of the closing borders; news highlighting the rough conditions of the migrant workers working in Singapore in packed dormitories where cases were on a rise—were just some of the anxiety and dismay laden news that was collectively encountered on a daily or hourly basis. I saw my actions of erasure by cutting that I used over the news pieces as a coping mechanism. The final works only had a suggestion of the news articles or imagery. Each piece of the Jali cut-out work was named after the day, for example, From April 10th…, since it felt like a memorial for that particular day.

![]()

![]() Images

^^^

From

May15..., 2021, from the series ‘Echo’. Acrylic

paint, found newsprint paper on canvas 115 x 76 cm

Images

^^^

From

May15..., 2021, from the series ‘Echo’. Acrylic

paint, found newsprint paper on canvas 115 x 76 cm

These works could be seen as palimpsestic overwriting, yet I would say there is a fundamental difference between that process and using erasure as an artistic tool. I see my actions and erasure of sections of news media as its own powerplay employing reductive methods as an act of philosophical exigency. It could also be seen as unearthing new modes of framing, voicing, and thinking about a subject. The writers of historical manuscripts (palimpsests) were hardly ever bothered about the content of the text that had disappeared over time or had been consciously erased by them. This is rarely the case with an artist who paints over a word or a writer who cancels words on printed pages, or a collective that savagely annotates some objectionable document. It mattered to Robert Rauschenberg that it was a de Kooning drawing he was trying to erase (Erased de Kooning Drawing, 1953), just as it mattered to Marcel Broodthaer that he was blacking out Mallarmé’s famous poem (Un coup de dés jamais n'abolira le hasard (A throw of the dice will never abolish chance, 1969). In the same way, Derrida’s placement of a cross mark on a fundamental term of metaphysics was intentional.8 Similarly, in my cut-out surfaces of Fragments & Echo , by acknowledging the used news articles date, as the title of the works, the altered material presence of the news trace in my cut-out surfaces from the series seeks to open up new modes of thinking about that day, its trace and the gaps that are formed between media and perception.

Notes:

1. Berger, John. “A Man with Tousled Hair”, The Shape of a Pocket. Vintage international, 2003.

2. Abbas, Masooma. “Ornamental Jālīs of the Mughals and Their Precursors” International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 6, No. 3; March 2016

3. Smith (n.d.) the lattices at Belur are twenty-eight in number derived from the Early Chalukyan Style of Southern India; See Tadgell (1990, pp. 137-138) plates 98, 100b, 122 and 158c for lattices of pre-Islamic Hindu period.

4. Abbas, Masooma. “Ornamental Jālīs of the Mughals and Their Precursors” International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 6, No. 3; March 2016

5. Derrida, Jacques. Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, 97

6. Merewether, Charles. “The Fact Remains”. In ISSUE 08: Erase. Singapore: Lasalle College of the Arts, 2019. pp.51-52

7. Merewether, Charles. “The Fact Remains”. In ISSUE 08: Erase. Singapore: Lasalle College of the Arts, 2019. pp.51-52

8. Rubinstein, Raphael. “Missing: erasure | Must include: erasure”, Under Erasure website, 2018. Pierogi Gallery, https://www.under-erasure.com/essay-by-raphael-rubinstein/. Accessed 6th December 2020

About the contributor:

Zoya Chaudhary is an artist born in India and a resident of Singapore for the last nine years. Working across mediums including installation, video, cut-out collage & painting, Chaudhary’s practice focuses on perception and its fragmentation in today’s media informed world. She is interested in the idea of the origins of information being filtered through various apparatus as it passes through the ever-changing reality of human subjectivity. Her works begin with the personal, and then build to consider ways the personal interacts with larger public narrative.

Chaudhary graduated with MA in Fine Arts from LASALLE College of the Arts in partnership with Goldsmiths, University of London in 2021. She has worked as a graphic artist, illustrator and designer in India and Singapore, before she started a dedicated art practice in 2016. Since her parents were from a theatre background she spent her formative years watching, performing and designing for several theatre productions. Chaudhary has been invited to show her art in several group exhibitions and art fairs in Singapore and the Netherlands since 2012. Her first solo exhibition Lost and Found-Singapore was held in August 2018 at Utterly Art Gallery, Singapore. Her painting Thinking Tamil, Talking Singlish, Eating Chinese received the Art Gemini Award, 2019. Website: https://zoyachaudhary.com Instagram: @zoyachaudhary_studio

Fragments & Echo

In the series of works called Fragments & Echo, I started with gluing sheets of newsprint paper on canvas. I then indeterminately scratched out portions of the surface. I had been occupied with the idea of filters (both perceptual and conceptual) and the correlation with screens as a type of filter or viewing device. The idea of the artwork taking on the characteristics of a filter seemed exciting. I started using repetitive shapes forming Jali-inspired patterns to cut-out sections from a sheet of newspaper stuck to a thin canvas, transforming into a mesh-like form. During this process I was trying to better understand the subjective filters I apply when viewing the mediated public narrative that is given to us through media. I thought about the juxtaposition of the rhythmic patterns of my presence, my breath, my daily routines with the media information I was working with. To visually present this feeling I traced a combination of two or three existing Jali pattern designs from architectural Jali drawings. Combining repetitive patterns, some determinate, some indeterminate, I would cut over the traced lines on the surface. The neatness of the cut-out forms varied with the state of mind I was in. By cutting the geometric forms and burning holes with incense sticks and a kitchen lighter, I transformed the surface into a mesh-like form. I started work on the first Jali work From March 18… from the series Fragments & Echo, around the time Singapore was in its lockdown due to the onset of the global COVID-19 pandemic. The local newspaper at that point was filled with virus-related news that depicted the anxiety and panic that could be felt across the globe. Taking newsprint paper from a single day, I used household tools to create a surface with suggestions of the news but transformed it into something that was not very definitive and open to interpretation. While cutting out patterns, I would get carried away by the repetitive actions, at times forgetting what I was cutting. The forms, images, and text became abstract material that I was shaping. But at other times I would stop and read or re-read the news article and take in the information. Sometimes, I would avoid cutting out an immigrant child's face, at other times I would want to cut-out a certain news piece with a statistical chart of a certain country’s virus death toll, rendering it invisible. News about jobless migrant workers from poor neighbouring countries desperate to get out of Thailand out of fear of the closing borders; news highlighting the rough conditions of the migrant workers working in Singapore in packed dormitories where cases were on a rise—were just some of the anxiety and dismay laden news that was collectively encountered on a daily or hourly basis. I saw my actions of erasure by cutting that I used over the news pieces as a coping mechanism. The final works only had a suggestion of the news articles or imagery. Each piece of the Jali cut-out work was named after the day, for example, From April 10th…, since it felt like a memorial for that particular day.

These works could be seen as palimpsestic overwriting, yet I would say there is a fundamental difference between that process and using erasure as an artistic tool. I see my actions and erasure of sections of news media as its own powerplay employing reductive methods as an act of philosophical exigency. It could also be seen as unearthing new modes of framing, voicing, and thinking about a subject. The writers of historical manuscripts (palimpsests) were hardly ever bothered about the content of the text that had disappeared over time or had been consciously erased by them. This is rarely the case with an artist who paints over a word or a writer who cancels words on printed pages, or a collective that savagely annotates some objectionable document. It mattered to Robert Rauschenberg that it was a de Kooning drawing he was trying to erase (Erased de Kooning Drawing, 1953), just as it mattered to Marcel Broodthaer that he was blacking out Mallarmé’s famous poem (Un coup de dés jamais n'abolira le hasard (A throw of the dice will never abolish chance, 1969). In the same way, Derrida’s placement of a cross mark on a fundamental term of metaphysics was intentional.8 Similarly, in my cut-out surfaces of Fragments & Echo , by acknowledging the used news articles date, as the title of the works, the altered material presence of the news trace in my cut-out surfaces from the series seeks to open up new modes of thinking about that day, its trace and the gaps that are formed between media and perception.

Notes:

1. Berger, John. “A Man with Tousled Hair”, The Shape of a Pocket. Vintage international, 2003.

2. Abbas, Masooma. “Ornamental Jālīs of the Mughals and Their Precursors” International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 6, No. 3; March 2016

3. Smith (n.d.) the lattices at Belur are twenty-eight in number derived from the Early Chalukyan Style of Southern India; See Tadgell (1990, pp. 137-138) plates 98, 100b, 122 and 158c for lattices of pre-Islamic Hindu period.

4. Abbas, Masooma. “Ornamental Jālīs of the Mughals and Their Precursors” International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 6, No. 3; March 2016

5. Derrida, Jacques. Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, 97

6. Merewether, Charles. “The Fact Remains”. In ISSUE 08: Erase. Singapore: Lasalle College of the Arts, 2019. pp.51-52

7. Merewether, Charles. “The Fact Remains”. In ISSUE 08: Erase. Singapore: Lasalle College of the Arts, 2019. pp.51-52

8. Rubinstein, Raphael. “Missing: erasure | Must include: erasure”, Under Erasure website, 2018. Pierogi Gallery, https://www.under-erasure.com/essay-by-raphael-rubinstein/. Accessed 6th December 2020

About the contributor:

Zoya Chaudhary is an artist born in India and a resident of Singapore for the last nine years. Working across mediums including installation, video, cut-out collage & painting, Chaudhary’s practice focuses on perception and its fragmentation in today’s media informed world. She is interested in the idea of the origins of information being filtered through various apparatus as it passes through the ever-changing reality of human subjectivity. Her works begin with the personal, and then build to consider ways the personal interacts with larger public narrative.

Chaudhary graduated with MA in Fine Arts from LASALLE College of the Arts in partnership with Goldsmiths, University of London in 2021. She has worked as a graphic artist, illustrator and designer in India and Singapore, before she started a dedicated art practice in 2016. Since her parents were from a theatre background she spent her formative years watching, performing and designing for several theatre productions. Chaudhary has been invited to show her art in several group exhibitions and art fairs in Singapore and the Netherlands since 2012. Her first solo exhibition Lost and Found-Singapore was held in August 2018 at Utterly Art Gallery, Singapore. Her painting Thinking Tamil, Talking Singlish, Eating Chinese received the Art Gemini Award, 2019. Website: https://zoyachaudhary.com Instagram: @zoyachaudhary_studio

Currents is a collaboration between the Centre of Visual Art (CoVA) at the University of Melbourne and the School of Design, University of Western Australia, and is funded through the Schenberg International Arts Collaboration Program. The Advisory Board and Editorial Committee are comprised of staff and graduate students from across the University of Melbourne and the University of Western Australia.

Currents acknowledges the traditional owners and ongoing custodians of the land on which this journal is produced—the Boonwurung and Wurundjeri people of the Eastern Kulin Nation and Whadjuk people. We pay our respects to land, ancestors and Elders, and know that education involves working with their guidance to improve the lives of all.

ISSN 2652-8207

![]()

![]()

Currents acknowledges the traditional owners and ongoing custodians of the land on which this journal is produced—the Boonwurung and Wurundjeri people of the Eastern Kulin Nation and Whadjuk people. We pay our respects to land, ancestors and Elders, and know that education involves working with their guidance to improve the lives of all.

ISSN 2652-8207