Terms and Conditions: Re-examining Singapore Art History Through the Art Making Experiences of Early Malay Women Artists

Nurdiana Rahmat

To cite this contribution:

Rahmat, Nurdiana. ‘Terms and Conditions: Re-examining Singapore Art History Through the Art Making Experiences of Early Malay Women Artists’. Currents Journal, Archipelagic Encounters (2021), https://currentsjournal.net/terms-and-conditions

Download this article ︎︎︎PDF

Keywords:

Women artists, Intersectional feminism, Malay artists, Singapore art history, APAD

Abstract:One of the key approaches to the study of women artists is the introduction of feminist interventions to art history by challenging, questioning and rewriting histories to include the voices of women who have been erased in these stories. By applying an intersectional feminist intervention to the study of Malay women artists in Singapore, this article will dig deeper into the development of Malay women artists through the archives of Singapore’s longest-running art society for Malay artists, Angkatan Pelukis Aneka Daya (Association of Artists of Various Resources, APAD) to recover and resurface key artistic contributions made by its early female members, Rohani Ismail, Hamidah Suhaimi, Maisara (Sara) Dariat and Rosma Mahyuddin Guha. The limitations they face in their respective art making experiences and how they cope with these challenges, as well as a re-examination of the support given towards their artistic development through exhibition opportunities, provides key insights to the systemised exclusion of Malay women artists’ contributions to Singapore’s art history.

[Figure 1] Minister for Culture, S Rajaratnam launched the

exhibition organised by APAD which was held at Victoria Memorial Hall on 26

December 1963. From left: Hamidah Suhaimi, Rohani Ismail, Marhaban, Abdul

Ghani, Ramli, S Mohdir and Mustafa. Image credit: Abdul Ghani Hamid, Pameran,

Published by Angkatan Pelukis Aneka Daya (Association of Artists of Various

Resources, APAD), Pg. 13.

[Figure 1] Minister for Culture, S Rajaratnam launched the

exhibition organised by APAD which was held at Victoria Memorial Hall on 26

December 1963. From left: Hamidah Suhaimi, Rohani Ismail, Marhaban, Abdul

Ghani, Ramli, S Mohdir and Mustafa. Image credit: Abdul Ghani Hamid, Pameran,

Published by Angkatan Pelukis Aneka Daya (Association of Artists of Various

Resources, APAD), Pg. 13.

In November 2020, a

retrospective of artist Georgette Chen at National Gallery Singapore featured a

work titled Rohani (1963); a portrait of Rohani Ismail by Chen, one of

Chen’s students at the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA). The painting was

completed in 1963 and during this time, Rohani Ismail was one of the founding

members of Singapore’s longest running art society for Malay artists, Angkatan

Pelukis Aneka Daya (Association of Artists of Various Resources, APAD). The

accompanying text label made a mention about Rohani Ismail’s membership with

APAD but not much else, relegating Rohani to a painting subject rather than

acknowledging her as the significant artist that she was. This painting could

have been a useful entry point to expand the discourse on women artists’

contributions to Singapore art history by providing further context to

practices of women artists from Malay and other minority community groups. This

was symptomatic of the larger trend in the Singaporean art historical

landscape: the achievements of women artists from Malay and other minority

community groups do not receive an appropriate amount of attention. Using this

painting of Rohani Ismail, audiences to this exhibition will only learn about

Rohani Ismail as a painterly subject, and not as an artist in her own right.

The scholarship of artistic practices of Malay artists in Singapore has been limited, which makes the study on the artistic practices of Singapore Malay women artists even more scarce. Past research on Malay artists in Singapore by Syed Muhammad Hafiz bin Syed Nasir, Derelyn Chua Jialing and Yeow Ju Li explore how Malay artists in Singapore were marginalised by the institutions of art history by probing into factors related to the political construction of the Malay identity, its problems and how they impacted the artistic development of Malay artists in Singapore. Their studies were mostly focused on the practices of Malay male artists and offered limited information on Malay women artists. My critique was amplified by further studies made of the publications, Women Artists in Singapore (2011) and Singapore’s Visual Artists (2015).

Singapore’s Visual Artists was produced by the National Arts Council (NAC), a statutory board under the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth (MCCY), made available in print and online. Featuring over 280 Singaporean and Singapore-based artists, NAC described the book as a manual or directory which ‘functions as a profiling platform to give visibility to our artists and their works to international audiences.’1 It was intended as a resource for the wider public to know key figures in the Singapore visual arts community. There were around 28 Malay artists featured; ceramic artist Suriani Suratman and performance artist Lina Adam were the only two Malay women artists featured in the publication.2

In 2011, curator Bridget Tracy Tan published the book Women Artists in Singapore which was commissioned by National Heritage Board; one of the statutory boards under then Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts (MICA). Surrealist artist Rosihan Dahim noted that, ‘although well-presented graphically, I am surprised after reading the newly launched art book…. there is no in-depth view on the history of Malay women artists or even reference to their existence… there should be deeper research on Malay women artists before publishing such a book.’3

Tan did write about one Malay woman artist, Neng (born Aminah Bte Mohd Sa’at), whose practice incorporated a rich combination of text, architectural visual elements and graphic design.4 In her introduction to the text, Tan highlighted that while finding gaps in the book was inevitable, any compilation of artists naturally formed a ‘selection criteria’. She described the women selected as ‘visibly renowned, as teachers of their craft and as artists whose works have been collected by national institutions.’5 The artists selected also had participated in local and international exhibitions, received awards for their work and produced an impressive oeuvre.

Professor Tommy Koh, Singapore’s ambassador-at-large at Ministry of Foreign Affairs and then-Chairman of the National Heritage Board, acknowledged in his foreword for the book that the selection of women artists was,

Manifested over a period of close to ten years, the abovementioned examples served as observations of defining moments in the publishing of Singapore’s art history where Malay women artists were not included, and if they were, their representation presented a stark contrast to their fellow women and Malay artistic contemporaries. This situation had compelled me to question why have Malay women artists remained an “invisible presence” throughout Singapore’s art history? What has caused the lack of visibility, reception and engagement with their practices and contributions by curators, art historians and fellow artists —all of whom were part of the art ecosystem that formed the institutions of Singapore’s art history?

One of the key approaches to the study of women artists of the past was the introduction of feminist interventions into art history by challenging, questioning and rewriting histories to include the voices of women who have been erased in the stories about the past. At the core of their principle, feminist interventions in art history not only revived lost narratives but critically studied the systems and processes that rendered women artists invisible in the first place.

Now more than ever, feminist art history should take on the approach of ‘intersectional feminist interventions’ where ‘intersectional’ refers to the process of ‘placing those who currently [were] marginalised in the centre’ and intersectionality in feminist theories as ‘the most effective way to resist efforts to compartmentalise experiences and undermine potential collective action.’7

Even though there has been research done on Malay artists, this article will take a distinct research approach by focusing on the art making experiences of Singapore Malay women artists.8 This article will apply an intersectional feminist intervention into existing research on Malay and women artists in Singapore, by beginning with a study on the female members of Singapore’s longest running art society for Malay artists, Angkatan Pelukis Aneka Daya (Association of Artists of Various Resources, APAD).

A series of analyses will be conducted on the historical conditions that have contributed to the paucity of research and writing on Malay women artists which further contributed to their exclusion from the narratives of modern art history in Singapore. By decentralising the existing study of women artists in local art history and placing the central focus on Malay women artists, this article aims to avoid essentialising women artists’ experiences and to diversify existing study of women artists in Singapore.

In the effort to begin the discussion on Malay women artists in Singapore, this article will refer to one of the earliest feminist art history texts, Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? (1971) by Linda Nochlin and juxtapose her key strategies with studies done by researchers from the region such as Yvonne Low and June Yap to draw on some of the unique regional contexts that shape this particular discussion.

Rohani Ismail, Hamidah Suhaimi and the beginnings of the Angkatan Pelukis Aneka Daya (Association of Artists of Various Resources, APAD)

In her essay Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?, Linda Nochlin called for the need to interrogate and rationalise the problems related to women artists by ‘probing some of the limitations of the discipline of art history itself.’9 Through her own re-examination of the Singapore art history, Yvonne Low asserted that nationalistic pursuits during post-war British Malaya made the distinction between ‘amateur’ and ‘professional’ artists even more apparent due to the collective search for a Malayan identity and the ‘founding of NAFA in 1938 and the postwar YMCA Art Club and Chinese YMCA Art Club for “awakening” and developing an interest in the visual arts development of art history in Singapore’.10 Low argued that there were already modern art practices going on in Singapore even before 1938 through the activities of the Singapore Art Club.11

This distinction between ‘amateur’ and ‘professional’ had influenced the presence and impact of supposedly ‘amateur’ artists in the chronology of modern art in Singapore. Low highlighted that artists in the Singapore Art Club were skilful in a range of art forms, but were more focused on contributing their work through social and charitable platforms rather than seeking professional and financial pursuits from their art. Inspired by Low’s use of newspaper archives to re-examine the canonised history of Singapore’s art landscape, this article will apply a similar archival research on APAD’s history to uncover artistic contributions made by their Malay women members.

From the second to sixth of March 2013, APAD mounted the exhibition Our Pioneer Artists: Malay Visual Art Practices from Post-War Period at the Singapore Calligraphy Exhibition Hall to commemorate its 50th anniversary. As part of the celebration, the exhibition showcased the work of 17 of the association’s pioneer members, which was, as stated by Abdul Rahman Rais in the foreword to the exhibition catalogue, a ‘rare opportunity for APAD to contribute towards the historical developments of the visual art from post-war period by our early pioneers.’12 Rosma Mahyudin Guha was the only Malay woman artist featured in the exhibition.

In writing about the event, Berita Harian reported that Rosma Guha was the first female member of APAD since the early 1960s.13 However, further research into newspaper archives revealed that one of earliest artistic activities by Malay artists involved the participation of two artists Hamidah Suhaimi and Rohani Ismail.

On 1 July 1962, Hamidah Suhaimi joined forces with six other artists—Abdul Ghani Hamid, S Mohdir, Marhaban Kasman, Mas Ali Sabran, Ahmin H Noh and Mustafa Yassin—to create their own association specifically for Singapore Malay artists.14 By 29 July 1962, Angkatan Pelukis Aneka Daya (Association of Artists of Various Resources, APAD) was officially formed, at a meeting between five Malay artists, who came up with the society’s motto of ‘Sa-chipta menchipta’ (‘Together We Create’).15

APAD collaborated again with Lembaga Tetap Kongress (Permanent Congress Board for Malay Literature and Culture, LTK) on an exhibition [Figure 1]. The exhibition, held at Victoria Memorial Hall, was launched on 26 December 1963 by then Minister for Culture, S Rajaratnam, who shared that Malay artists ‘had once again come forward to exhibit their works of art of comparatively high standard.’16

In his review of this exhibition, Abdul Ghani wrote that Rohani Ismail ‘presents a group of works that includes a few portraits, still-lifes and others. Baju Merah is one of her works that still carries her unique style,’ and noted that Hamidah Suhaimi, ‘depicts the beauty of Malay women in a way that captures the heart.’ He goes on to say,

Despite their active contributions in APAD’s formative years, there was no mention of Rohani Ismail or Hamidah Suhaimi in APAD’s later projects, in particular, Our Pioneer Artists: Malay Visual Art Practices from Post-War Period exhibition catalogue of 2013. How did these two artists, who occupied prominent places in the records of APAD’s founding years, end up completely erased from this exhibition?

In 1963, Rohani Ismail married fellow artist S. Mahdar.18 She graduated from NAFA in the same year. Even though she was trained as an artist, painting became more of a hobby than a profession, as she found it challenging to sell her art and she could not focus solely on it after she was married.19 Nonetheless, she continued to be active in the exhibition circuit through the 1960s with APAD and with the Singapore Art Society in the 1970s.

In a similar vein, Hamidah Suhaimi did not have the luxury of being a painter as her sole profession. She was a teacher at Madrasah Ipoh Lane, and married Malaysian artist Mazli Ma’asom. In her married years, she was likely more active in Kuala Lumpur, where her husband was based.20 The historical effect was a definitive writing out of Hamidah’s significance in Singaporean art history.

Rohani Ismail’s experience as a Malay woman artist trained by NAFA should inspire further research on Malay female students at the school. Graduation catalogues from NAFA in the 1960s through the 1980s recorded at least one Malay female student in each cohort. What happened to these students after they graduated? Despite formal art training, financial challenges and personal commitments hindered both Rohani Ismail and Hamidah Suhaimi’s pursuit of becoming full-time artists in Singapore. Could other Malay women graduates of NAFA have faced similar challenges?

Conditions of Art and Exhibition Making: The presence/absence of Maisara (Sara) Dariat and Rosma Mahyudin Guha

Linda Nochlin’s seminal work examined the physical, social and political situations of art making and how the involvement of art institutions affected the development of the artist and the quality of his or her work. This was exemplified by the restrictions imposed on women artists, from the Renaissance period until the end of the nineteenth century, against the study of the male nude model. As drawing of the male nude model was critical and foundational to classical (institutional) artistic training, this disadvantage affected the skills and credibility of women artists.

Based on Nochlin’s reframing model, this article will re-examine the conditions of art making for Singapore Malay women artists by examining exhibition opportunities made available to them. This focus on exhibition participation reflects the shift in art history, particularly in the second half of the twentieth century, from a study of the artistic production of individual artists, to presentation of the views and opinions of curators.21

The rise of the curator occurred in Southeast Asia in this period as well. Exhibitions became important sites of discourse to understand artistic production in Southeast Asia, but also provided contextual framework in the positioning of the region within and outside its borders.22 Artists’ participation in exhibitions and the presentation of their work to a public audience not only reflected their professional standing, but also offered insights into the conditions of their environment and generates narratives that defined their immediate and wider communities.

In Singapore, an artist’s active participation in exhibitions was one of the factors that determined their position within the arts ecosystem. In Singapore’s Visual Artists (2016), it was specified that an artist’s presentation of his or her work in the last five years, as well as artistic contributions in Singapore and overseas, formed some of their key selection criteria.23 Hence, the more active artists were in the creation and presentation of their art, whether through their own efforts or in collaboration with others, the more impact they were seen to have created in the art ecosystem of Singapore.

Since the start of the 1970s, feminist art theories have introduced more inclusive strategies to look at, analyse and study art history and art making. This period marked a pivotal moment in the history of women’s fight for equal rights as second wave feminism began to gain momentum in Europe and America. By 1975, the United Nations declared an International Women’s Year in a push for additional efforts to end discrimination against women.24

That same year in Singapore, the Singapore Art Society organised the exhibition, International Women’s Year, to commemorate this event. This exhibition included participation by artists Georgette Chen, Rohani Ismail and sculptor Annaratnam Gunaratnam. It was a meaningful attempt at presenting works by artists from diverse social and ethnic backgrounds, each specialising in different genres of the visual arts. Particularly in the context of Singapore communities, such intersectional approaches to exhibition making was critical to ensure diverse stories informing women’s lived experiences were reflected through this selection of artists. It was also from this very same exhibition where Rohani’s frustrations at making art was reported in stark contrast to Chen’s art making experience where she ‘breathes, eats and sleeps art.’25

During this time, while APAD’s founding female members Hamidah Suhaimi and Rohani Ismail decreased their art activities, a new member of APAD–Maisara (Sara) Dariat emerged as one of their most active female members.

Sara worked full-time as a journalist and illustrator for two years before resigning to focus entirely on her artistic practice.26 She first exhibited her works in the exhibition, Contemporary 73, held at the Chinese Chamber of Commerce from 16 to 18 December 1973. Even though it was her first time exhibiting, it was reported that she ‘expresses herself confidently in her batik pieces.’27

She presented her batik painting, Terangbulan (Moonlight) [Figure 2], which was praised for skilfully depicting movements in visual forms. In this work, a kampung (village) house stood on stilts by a riverbed. Three small boats rested at the bottom-right of the frame. Using vertical lines parallel to the stilts holding the kampung house, Sara directed the audience’s gaze to a luminescent moon at the top-right of the frame. The consistency of the lines she used to move the viewer’s eyes from stilts to the moon, and then back down as they separated to portray glints of moonlight reflected on the calm water surface, harmonised the image. This movement of the gaze from stilts to moon, and then back down to elements below the kampung, encouraged the viewer to take in the entire composition in all its features. The confident engagement of the gaze, captured by the placement of vertical lines and organised mass of splashes, demonstrated Sara’s skilled wax-resist dye technique. The presence and absence of the ink and wax was cleverly used to generate a seamless optical movement. This work, her first to be exhibited, cemented her reputation as a talented batik painter who the art scene of the time should be watching.

![]() [Figure 2] Maisara (Sara) Dariat. Terangbulan.

1974. Batik. Size unknown. Image credit: Abdul Ghani Hamid, Pameran,

Published by Angkatan Pelukis Aneka Daya (Association of Artists of Various

Resources, APAD), Pg. 64.

[Figure 2] Maisara (Sara) Dariat. Terangbulan.

1974. Batik. Size unknown. Image credit: Abdul Ghani Hamid, Pameran,

Published by Angkatan Pelukis Aneka Daya (Association of Artists of Various

Resources, APAD), Pg. 64.

Sara Dariat achieved a significant milestone in her artistic career with her first solo exhibition at the National Library’s Auditorium from 5 to 8 November 1974. She was probably the first female member of APAD to receive a solo exhibition, as there are no other records of solo exhibitions by female members of APAD.

Through a display of over forty works, Sara introduced a new abstract-style of painting in her work [Figure 3]. A more effective sense of optical movement was achieved by applying her signature lines and circles.28 Unlike Rohani Ismail who had difficulties selling her work, Sara Dariat had sold about 30 artworks even before she embarked on her career as a full-time artist.29 It was clear that Sara’s art making experience was different from Hamidah and Rohani’s and seemed to parallel with the growing socio-political movement of women’s liberation.

![]() [Figure 3] Sara with her work for her solo exhibition.

Image credit: Image credit: Abdul Ghani Hamid, Pameran, Published by

Angkatan Pelukis Aneka Daya (Association of Artists of Various Resources,

APAD), Pg. 87.

[Figure 3] Sara with her work for her solo exhibition.

Image credit: Image credit: Abdul Ghani Hamid, Pameran, Published by

Angkatan Pelukis Aneka Daya (Association of Artists of Various Resources,

APAD), Pg. 87.

Despite her very best efforts in art making, there were no further records of Sara’s activities beyond 1975. Why did her success not sustain her artistic career and her position within the local art ecosystem? What happened to Sara and her artistic practices in the late 1970s?

An analysis of APAD’s exhibition activities through the late 1970s showed the society’s focus shifted towards promoting solo exhibitions by their male members. They showcased S Mohdir, Bakar Banafek, Effendi and another batik artist, Jaafar Latiff, all exhibitions opened in 1976. It was possible that this affected Sara’s artistic development. Further research must be conducted to examine Sara’s artistic activities within the society from the late 1970s to fully understand the conditions that affected her art making and exhibiting, which seemed to have gone into a premature decline, despite the momentum gained in the early 1970s. It was also notable to observe that leading to the 1980s, the emergence of Social Realism in art due to tensions arising from decolonialisation movements may also be the driving focus amongst artists and audiences alike during the time.

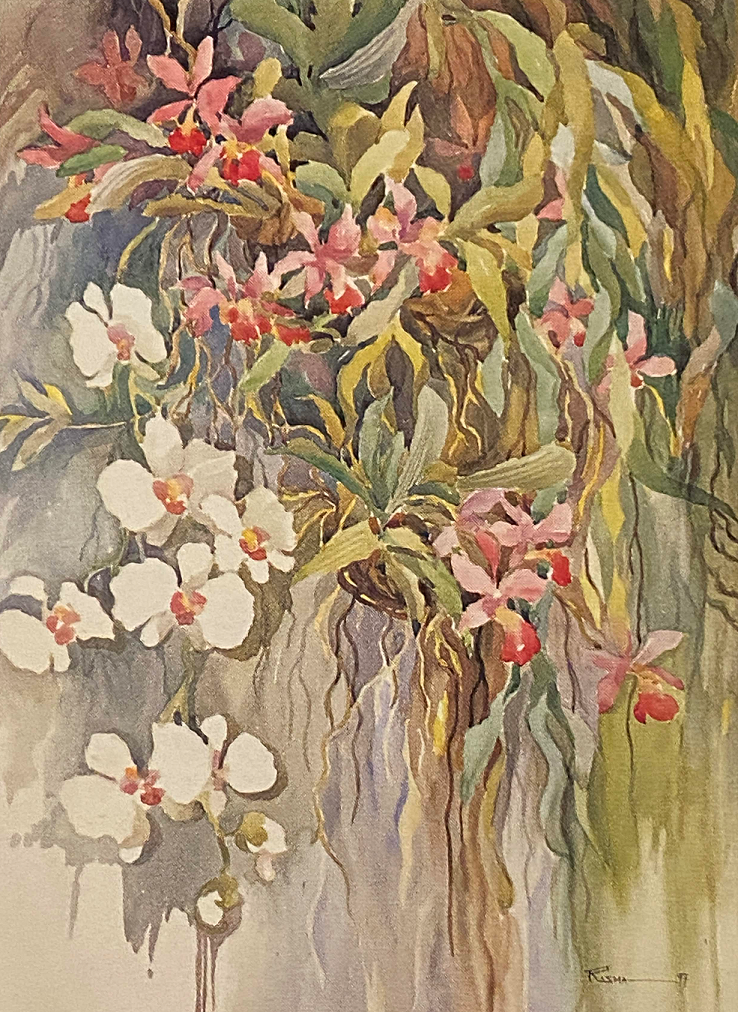

Another prominent female member of APAD who actively participated in the society’s exhibitions throughout the late 1980s to 1990s was Rosma Mahyuddin Guha. Born in 1932, in Padang, on the island of Sumatra, her activities as an artist were largely through opportunities offered to her by the art societies she was affiliated with. She is a watercolour artist and a member of the Singapore Watercolour Society, Singapore Art Society and APAD. At 88 years old, she is no longer active as an artist, largely because she is in poor health.30

![]()

![]() [Figure 4] Rosma Mahyuddin Guha. Array of Orchids. 1997. Watercolour.

Size unknown. Image credit: Singapore Fine Arts Index, published by

Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts and Raffles Fine Arts Auctioneers Pte Ltd, 1998,

Pg. 87.

[Figure 5] Rosma Mahyuddin Guha. Pak Tani. 1997. Watercolour. Size

unknown. Image credit: Singapore Fine Arts Index, published by Nanyang

Academy of Fine Arts and Raffles Fine Arts Auctioneers Pte Ltd, 1998, Pg. 87.

[Figure 4] Rosma Mahyuddin Guha. Array of Orchids. 1997. Watercolour.

Size unknown. Image credit: Singapore Fine Arts Index, published by

Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts and Raffles Fine Arts Auctioneers Pte Ltd, 1998,

Pg. 87.

[Figure 5] Rosma Mahyuddin Guha. Pak Tani. 1997. Watercolour. Size

unknown. Image credit: Singapore Fine Arts Index, published by Nanyang

Academy of Fine Arts and Raffles Fine Arts Auctioneers Pte Ltd, 1998, Pg. 87.

Rosma was most active in the exhibition circuit during the late 1980s through the 1990s. Her participation in shows organised by APAD, Shell Art Exhibition, Singapore Art Society and Singapore Watercolour Society had given her significant recognition as a professional artist by the public media and art institutions, putting her in the same league as contemporaries such as Abdul Ghani Hamid, Jaafar Latiff and Ong Chye Cho.31

Like other watercolour artists of her generation, such as Ong Kim Seng, and the more senior Lim Cheng Hoe, Rosma is a self-taught artist. She started drawing when she was four years old, and at that time, she was already living in Singapore, in her Kembangan home. She did not receive formal art training at NAFA, the only tertiary art institution when she was a young adult in the early 1950s.32 However, she did join the YMCA Art Club and the British Council during this time to pursue her interest in art as a hobby.33 She only started to pursue art actively as a professional artist in the 1980s, after she retired from her job as a social welfare officer.34

The scholarship of artistic practices of Malay artists in Singapore has been limited, which makes the study on the artistic practices of Singapore Malay women artists even more scarce. Past research on Malay artists in Singapore by Syed Muhammad Hafiz bin Syed Nasir, Derelyn Chua Jialing and Yeow Ju Li explore how Malay artists in Singapore were marginalised by the institutions of art history by probing into factors related to the political construction of the Malay identity, its problems and how they impacted the artistic development of Malay artists in Singapore. Their studies were mostly focused on the practices of Malay male artists and offered limited information on Malay women artists. My critique was amplified by further studies made of the publications, Women Artists in Singapore (2011) and Singapore’s Visual Artists (2015).

Singapore’s Visual Artists was produced by the National Arts Council (NAC), a statutory board under the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth (MCCY), made available in print and online. Featuring over 280 Singaporean and Singapore-based artists, NAC described the book as a manual or directory which ‘functions as a profiling platform to give visibility to our artists and their works to international audiences.’1 It was intended as a resource for the wider public to know key figures in the Singapore visual arts community. There were around 28 Malay artists featured; ceramic artist Suriani Suratman and performance artist Lina Adam were the only two Malay women artists featured in the publication.2

In 2011, curator Bridget Tracy Tan published the book Women Artists in Singapore which was commissioned by National Heritage Board; one of the statutory boards under then Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts (MICA). Surrealist artist Rosihan Dahim noted that, ‘although well-presented graphically, I am surprised after reading the newly launched art book…. there is no in-depth view on the history of Malay women artists or even reference to their existence… there should be deeper research on Malay women artists before publishing such a book.’3

Tan did write about one Malay woman artist, Neng (born Aminah Bte Mohd Sa’at), whose practice incorporated a rich combination of text, architectural visual elements and graphic design.4 In her introduction to the text, Tan highlighted that while finding gaps in the book was inevitable, any compilation of artists naturally formed a ‘selection criteria’. She described the women selected as ‘visibly renowned, as teachers of their craft and as artists whose works have been collected by national institutions.’5 The artists selected also had participated in local and international exhibitions, received awards for their work and produced an impressive oeuvre.

Professor Tommy Koh, Singapore’s ambassador-at-large at Ministry of Foreign Affairs and then-Chairman of the National Heritage Board, acknowledged in his foreword for the book that the selection of women artists was,

…not comprehensive. It neither mentions nor treats in detail several of my women artist friends, such as the late Sun Yee; second generation artists Lee Boon Ngan, Cheong Leng Guat, Rosma Guha, Sandy Tang, Sandy Wong, and the late Zee Mei Chua; third-generation artists Choo Ai Loon, Soh Siew Kiat and Tan Chin Chin; and the late and much loved Pacita Abad [sic].6

Manifested over a period of close to ten years, the abovementioned examples served as observations of defining moments in the publishing of Singapore’s art history where Malay women artists were not included, and if they were, their representation presented a stark contrast to their fellow women and Malay artistic contemporaries. This situation had compelled me to question why have Malay women artists remained an “invisible presence” throughout Singapore’s art history? What has caused the lack of visibility, reception and engagement with their practices and contributions by curators, art historians and fellow artists —all of whom were part of the art ecosystem that formed the institutions of Singapore’s art history?

One of the key approaches to the study of women artists of the past was the introduction of feminist interventions into art history by challenging, questioning and rewriting histories to include the voices of women who have been erased in the stories about the past. At the core of their principle, feminist interventions in art history not only revived lost narratives but critically studied the systems and processes that rendered women artists invisible in the first place.

Now more than ever, feminist art history should take on the approach of ‘intersectional feminist interventions’ where ‘intersectional’ refers to the process of ‘placing those who currently [were] marginalised in the centre’ and intersectionality in feminist theories as ‘the most effective way to resist efforts to compartmentalise experiences and undermine potential collective action.’7

Even though there has been research done on Malay artists, this article will take a distinct research approach by focusing on the art making experiences of Singapore Malay women artists.8 This article will apply an intersectional feminist intervention into existing research on Malay and women artists in Singapore, by beginning with a study on the female members of Singapore’s longest running art society for Malay artists, Angkatan Pelukis Aneka Daya (Association of Artists of Various Resources, APAD).

A series of analyses will be conducted on the historical conditions that have contributed to the paucity of research and writing on Malay women artists which further contributed to their exclusion from the narratives of modern art history in Singapore. By decentralising the existing study of women artists in local art history and placing the central focus on Malay women artists, this article aims to avoid essentialising women artists’ experiences and to diversify existing study of women artists in Singapore.

In the effort to begin the discussion on Malay women artists in Singapore, this article will refer to one of the earliest feminist art history texts, Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? (1971) by Linda Nochlin and juxtapose her key strategies with studies done by researchers from the region such as Yvonne Low and June Yap to draw on some of the unique regional contexts that shape this particular discussion.

Rohani Ismail, Hamidah Suhaimi and the beginnings of the Angkatan Pelukis Aneka Daya (Association of Artists of Various Resources, APAD)

In her essay Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?, Linda Nochlin called for the need to interrogate and rationalise the problems related to women artists by ‘probing some of the limitations of the discipline of art history itself.’9 Through her own re-examination of the Singapore art history, Yvonne Low asserted that nationalistic pursuits during post-war British Malaya made the distinction between ‘amateur’ and ‘professional’ artists even more apparent due to the collective search for a Malayan identity and the ‘founding of NAFA in 1938 and the postwar YMCA Art Club and Chinese YMCA Art Club for “awakening” and developing an interest in the visual arts development of art history in Singapore’.10 Low argued that there were already modern art practices going on in Singapore even before 1938 through the activities of the Singapore Art Club.11

This distinction between ‘amateur’ and ‘professional’ had influenced the presence and impact of supposedly ‘amateur’ artists in the chronology of modern art in Singapore. Low highlighted that artists in the Singapore Art Club were skilful in a range of art forms, but were more focused on contributing their work through social and charitable platforms rather than seeking professional and financial pursuits from their art. Inspired by Low’s use of newspaper archives to re-examine the canonised history of Singapore’s art landscape, this article will apply a similar archival research on APAD’s history to uncover artistic contributions made by their Malay women members.

From the second to sixth of March 2013, APAD mounted the exhibition Our Pioneer Artists: Malay Visual Art Practices from Post-War Period at the Singapore Calligraphy Exhibition Hall to commemorate its 50th anniversary. As part of the celebration, the exhibition showcased the work of 17 of the association’s pioneer members, which was, as stated by Abdul Rahman Rais in the foreword to the exhibition catalogue, a ‘rare opportunity for APAD to contribute towards the historical developments of the visual art from post-war period by our early pioneers.’12 Rosma Mahyudin Guha was the only Malay woman artist featured in the exhibition.

In writing about the event, Berita Harian reported that Rosma Guha was the first female member of APAD since the early 1960s.13 However, further research into newspaper archives revealed that one of earliest artistic activities by Malay artists involved the participation of two artists Hamidah Suhaimi and Rohani Ismail.

On 1 July 1962, Hamidah Suhaimi joined forces with six other artists—Abdul Ghani Hamid, S Mohdir, Marhaban Kasman, Mas Ali Sabran, Ahmin H Noh and Mustafa Yassin—to create their own association specifically for Singapore Malay artists.14 By 29 July 1962, Angkatan Pelukis Aneka Daya (Association of Artists of Various Resources, APAD) was officially formed, at a meeting between five Malay artists, who came up with the society’s motto of ‘Sa-chipta menchipta’ (‘Together We Create’).15

APAD collaborated again with Lembaga Tetap Kongress (Permanent Congress Board for Malay Literature and Culture, LTK) on an exhibition [Figure 1]. The exhibition, held at Victoria Memorial Hall, was launched on 26 December 1963 by then Minister for Culture, S Rajaratnam, who shared that Malay artists ‘had once again come forward to exhibit their works of art of comparatively high standard.’16

In his review of this exhibition, Abdul Ghani wrote that Rohani Ismail ‘presents a group of works that includes a few portraits, still-lifes and others. Baju Merah is one of her works that still carries her unique style,’ and noted that Hamidah Suhaimi, ‘depicts the beauty of Malay women in a way that captures the heart.’ He goes on to say,

One can find the meticulous palette of soft, cool and calming colours in a few of her works. What’s more captivating is Hamidah’s precision. She has clearly secured her position as an artist who is calm and romantic amongst the group of participating artists in this exhibition.17

Despite their active contributions in APAD’s formative years, there was no mention of Rohani Ismail or Hamidah Suhaimi in APAD’s later projects, in particular, Our Pioneer Artists: Malay Visual Art Practices from Post-War Period exhibition catalogue of 2013. How did these two artists, who occupied prominent places in the records of APAD’s founding years, end up completely erased from this exhibition?

In 1963, Rohani Ismail married fellow artist S. Mahdar.18 She graduated from NAFA in the same year. Even though she was trained as an artist, painting became more of a hobby than a profession, as she found it challenging to sell her art and she could not focus solely on it after she was married.19 Nonetheless, she continued to be active in the exhibition circuit through the 1960s with APAD and with the Singapore Art Society in the 1970s.

In a similar vein, Hamidah Suhaimi did not have the luxury of being a painter as her sole profession. She was a teacher at Madrasah Ipoh Lane, and married Malaysian artist Mazli Ma’asom. In her married years, she was likely more active in Kuala Lumpur, where her husband was based.20 The historical effect was a definitive writing out of Hamidah’s significance in Singaporean art history.

Rohani Ismail’s experience as a Malay woman artist trained by NAFA should inspire further research on Malay female students at the school. Graduation catalogues from NAFA in the 1960s through the 1980s recorded at least one Malay female student in each cohort. What happened to these students after they graduated? Despite formal art training, financial challenges and personal commitments hindered both Rohani Ismail and Hamidah Suhaimi’s pursuit of becoming full-time artists in Singapore. Could other Malay women graduates of NAFA have faced similar challenges?

Conditions of Art and Exhibition Making: The presence/absence of Maisara (Sara) Dariat and Rosma Mahyudin Guha

Linda Nochlin’s seminal work examined the physical, social and political situations of art making and how the involvement of art institutions affected the development of the artist and the quality of his or her work. This was exemplified by the restrictions imposed on women artists, from the Renaissance period until the end of the nineteenth century, against the study of the male nude model. As drawing of the male nude model was critical and foundational to classical (institutional) artistic training, this disadvantage affected the skills and credibility of women artists.

Based on Nochlin’s reframing model, this article will re-examine the conditions of art making for Singapore Malay women artists by examining exhibition opportunities made available to them. This focus on exhibition participation reflects the shift in art history, particularly in the second half of the twentieth century, from a study of the artistic production of individual artists, to presentation of the views and opinions of curators.21

The rise of the curator occurred in Southeast Asia in this period as well. Exhibitions became important sites of discourse to understand artistic production in Southeast Asia, but also provided contextual framework in the positioning of the region within and outside its borders.22 Artists’ participation in exhibitions and the presentation of their work to a public audience not only reflected their professional standing, but also offered insights into the conditions of their environment and generates narratives that defined their immediate and wider communities.

In Singapore, an artist’s active participation in exhibitions was one of the factors that determined their position within the arts ecosystem. In Singapore’s Visual Artists (2016), it was specified that an artist’s presentation of his or her work in the last five years, as well as artistic contributions in Singapore and overseas, formed some of their key selection criteria.23 Hence, the more active artists were in the creation and presentation of their art, whether through their own efforts or in collaboration with others, the more impact they were seen to have created in the art ecosystem of Singapore.

Since the start of the 1970s, feminist art theories have introduced more inclusive strategies to look at, analyse and study art history and art making. This period marked a pivotal moment in the history of women’s fight for equal rights as second wave feminism began to gain momentum in Europe and America. By 1975, the United Nations declared an International Women’s Year in a push for additional efforts to end discrimination against women.24

That same year in Singapore, the Singapore Art Society organised the exhibition, International Women’s Year, to commemorate this event. This exhibition included participation by artists Georgette Chen, Rohani Ismail and sculptor Annaratnam Gunaratnam. It was a meaningful attempt at presenting works by artists from diverse social and ethnic backgrounds, each specialising in different genres of the visual arts. Particularly in the context of Singapore communities, such intersectional approaches to exhibition making was critical to ensure diverse stories informing women’s lived experiences were reflected through this selection of artists. It was also from this very same exhibition where Rohani’s frustrations at making art was reported in stark contrast to Chen’s art making experience where she ‘breathes, eats and sleeps art.’25

During this time, while APAD’s founding female members Hamidah Suhaimi and Rohani Ismail decreased their art activities, a new member of APAD–Maisara (Sara) Dariat emerged as one of their most active female members.

Sara worked full-time as a journalist and illustrator for two years before resigning to focus entirely on her artistic practice.26 She first exhibited her works in the exhibition, Contemporary 73, held at the Chinese Chamber of Commerce from 16 to 18 December 1973. Even though it was her first time exhibiting, it was reported that she ‘expresses herself confidently in her batik pieces.’27

She presented her batik painting, Terangbulan (Moonlight) [Figure 2], which was praised for skilfully depicting movements in visual forms. In this work, a kampung (village) house stood on stilts by a riverbed. Three small boats rested at the bottom-right of the frame. Using vertical lines parallel to the stilts holding the kampung house, Sara directed the audience’s gaze to a luminescent moon at the top-right of the frame. The consistency of the lines she used to move the viewer’s eyes from stilts to the moon, and then back down as they separated to portray glints of moonlight reflected on the calm water surface, harmonised the image. This movement of the gaze from stilts to moon, and then back down to elements below the kampung, encouraged the viewer to take in the entire composition in all its features. The confident engagement of the gaze, captured by the placement of vertical lines and organised mass of splashes, demonstrated Sara’s skilled wax-resist dye technique. The presence and absence of the ink and wax was cleverly used to generate a seamless optical movement. This work, her first to be exhibited, cemented her reputation as a talented batik painter who the art scene of the time should be watching.

[Figure 2] Maisara (Sara) Dariat. Terangbulan.

1974. Batik. Size unknown. Image credit: Abdul Ghani Hamid, Pameran,

Published by Angkatan Pelukis Aneka Daya (Association of Artists of Various

Resources, APAD), Pg. 64.

[Figure 2] Maisara (Sara) Dariat. Terangbulan.

1974. Batik. Size unknown. Image credit: Abdul Ghani Hamid, Pameran,

Published by Angkatan Pelukis Aneka Daya (Association of Artists of Various

Resources, APAD), Pg. 64.

Sara Dariat achieved a significant milestone in her artistic career with her first solo exhibition at the National Library’s Auditorium from 5 to 8 November 1974. She was probably the first female member of APAD to receive a solo exhibition, as there are no other records of solo exhibitions by female members of APAD.

Through a display of over forty works, Sara introduced a new abstract-style of painting in her work [Figure 3]. A more effective sense of optical movement was achieved by applying her signature lines and circles.28 Unlike Rohani Ismail who had difficulties selling her work, Sara Dariat had sold about 30 artworks even before she embarked on her career as a full-time artist.29 It was clear that Sara’s art making experience was different from Hamidah and Rohani’s and seemed to parallel with the growing socio-political movement of women’s liberation.

[Figure 3] Sara with her work for her solo exhibition.

Image credit: Image credit: Abdul Ghani Hamid, Pameran, Published by

Angkatan Pelukis Aneka Daya (Association of Artists of Various Resources,

APAD), Pg. 87.

[Figure 3] Sara with her work for her solo exhibition.

Image credit: Image credit: Abdul Ghani Hamid, Pameran, Published by

Angkatan Pelukis Aneka Daya (Association of Artists of Various Resources,

APAD), Pg. 87.

Despite her very best efforts in art making, there were no further records of Sara’s activities beyond 1975. Why did her success not sustain her artistic career and her position within the local art ecosystem? What happened to Sara and her artistic practices in the late 1970s?

An analysis of APAD’s exhibition activities through the late 1970s showed the society’s focus shifted towards promoting solo exhibitions by their male members. They showcased S Mohdir, Bakar Banafek, Effendi and another batik artist, Jaafar Latiff, all exhibitions opened in 1976. It was possible that this affected Sara’s artistic development. Further research must be conducted to examine Sara’s artistic activities within the society from the late 1970s to fully understand the conditions that affected her art making and exhibiting, which seemed to have gone into a premature decline, despite the momentum gained in the early 1970s. It was also notable to observe that leading to the 1980s, the emergence of Social Realism in art due to tensions arising from decolonialisation movements may also be the driving focus amongst artists and audiences alike during the time.

Another prominent female member of APAD who actively participated in the society’s exhibitions throughout the late 1980s to 1990s was Rosma Mahyuddin Guha. Born in 1932, in Padang, on the island of Sumatra, her activities as an artist were largely through opportunities offered to her by the art societies she was affiliated with. She is a watercolour artist and a member of the Singapore Watercolour Society, Singapore Art Society and APAD. At 88 years old, she is no longer active as an artist, largely because she is in poor health.30

Rosma was most active in the exhibition circuit during the late 1980s through the 1990s. Her participation in shows organised by APAD, Shell Art Exhibition, Singapore Art Society and Singapore Watercolour Society had given her significant recognition as a professional artist by the public media and art institutions, putting her in the same league as contemporaries such as Abdul Ghani Hamid, Jaafar Latiff and Ong Chye Cho.31

Like other watercolour artists of her generation, such as Ong Kim Seng, and the more senior Lim Cheng Hoe, Rosma is a self-taught artist. She started drawing when she was four years old, and at that time, she was already living in Singapore, in her Kembangan home. She did not receive formal art training at NAFA, the only tertiary art institution when she was a young adult in the early 1950s.32 However, she did join the YMCA Art Club and the British Council during this time to pursue her interest in art as a hobby.33 She only started to pursue art actively as a professional artist in the 1980s, after she retired from her job as a social welfare officer.34

She was most active in the

late 1980s, when her reputation as an artist gave her the opportunity to write

simple art tutorials in an art column in The Straits Times newspaper.35 In December 1989 and June

1991, she participated in Discovery Art Exhibitions organised by Shell

Art Exhibition; the catalogue described her as skilful in painting orchids, ‘with

great efficiency and delicacy using the watercolour technique.’36

Rosma Guha’s last public appearance as a visual artist was in APAD’s exhibition, Our Pioneer Artists: Malay Visual Art Practices from Post-War Period in 2013. Despite her contributions to the local art scene and meeting the selection criteria which informed both Bridget Tracy Tan’s Women Artists in Singapore (2011) and National Arts Council’s Singapore’s Visual Artist (2016), Rosma Guha was still excluded from these projects.

Apart from local newspaper reports, there has been little research and writing conducted on Rosma Guha’s work and practice despite her prolific work from the 1980s to the 2010s. Was it also possible that Rosma Guha’s exclusion was abetted by the very system that supported her artistic endeavours? This perception was drawn from the fact that the institutions of art themselves, including in Singapore, were deeply gendered.37 In contemporary art, works that addressed critical socio-political events or engaged critically with historical references appear to be at the foreground of the art historical writings and discourse. Therefore, it may also be possible that Rosma Guha’s work was overlooked based on the subject matter of her paintings alone.

Two of Rosma Guha’s works did feature in the canonical catalogue Singapore Fine Arts Index 1998 by Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts: Array of Orchids and Pak Tani. In Array of Orchids [Figure 4], she demonstrated her adept abilities as a colourist, through her use of selection of colours that created a visual harmony, balancing the purple and white orchids against the shades of green foliage. Her arrangement of these colours was intentional, as they provided a natural frame for the white orchids to stand out in this work. She executed a smooth variegated wash to set the background and showcased a remarkable glazing technique in the floral petals. Her proficient use of colour washes created meaningful depths and shadows to the scene, demonstrating proficient control in one of fine art’s most unforgiving mediums.

In a rare portraiture work, Pak Tani [Figure 5], Rosma Guha demonstrated the range of her techniques as a skilled watercolour artist. Her expert control of the brush to apply the technique of negative painting gave a natural sense of light and environment. The different contours of colour shading created a clever composition of positive and negative spaces to give a sense of three-dimensional depth in this watercolour painting. Similar to An Array of Orchids, she played with lines to add realistic details to her subject’s facial expression, adding a nuanced sense of time to this static painting. She also applied just the right amount of cooler purple tones to give an otherwise neutral painting a subtle pop of colour to attract one’s eyes.

In watercolour paintings, varying depictions of Singapore’s landscapes such as the ubiquitous Singapore River or streets scenes with shophouses by her male contemporaries were highly lauded and recognized in Singapore’s art historical canon. It must be recognised that Rosma Guha’s focus on flowers further demonstrated her negotiations of space in the watercolour medium to create her own distinct subject matter and therefore, highlighted her unique standing as a talented watercolour artist.

Exploring the Intersections in Hamidah Jalil’s Hampatong series

Nochlin pointed out that one of the most common observations of women artist in the later part of the nineteenth and into the twentieth century was that most of them have or have had close connections to a more prominent male artistic personality.38 By applying this observation to Singapore Malay women artists, this article has highlighted the shared connections that some of these artists have as ‘artists’ wives’ or members of an art collective or society. While they may receive support to present their work, it was challenging for them to consistently participate in exhibitions and remain active in the local art ecosystem.

Hamidah Jalil is a self-taught artist who primarily works in the medium of painting. She started her artistic practice in the early 1990s, prompted by an unconventional dare made by her late husband, artist Mohammad Din Mohammad, after she gave a critique of his work.39 Working mostly with acrylic, Hamidah’s close connections with her Javanese roots, and Java’s position within the larger context of the shared traditions and cultures of the Nusantara, or the Malay Archipelago, informed the way she applied colours, patterns and styles in her painted works. She recalled that when she created her first painting, she had an image of a favourite batik print pattern in mind, and then started to develop that image further on canvas.

Hamidah’s earlier abstract style changed to more figurative forms when she created the first work from her Hampatong series in 1995 [Figure 6]. This series of eight paintings was created between 1995 and 1998 and the name Hampatong, was a play on the words ‘Hamidah’s patong (dolls)’. In this series, she created a central figure, or two characters, in the case of Hampatong V (1997) [Figure 7], framed by an assembly of patterns, which she drew from several indigenous cultures. She maintained a balance of earthy and vibrant tones by employing strong lines to accentuate and control the composition of colours. This balance of varying visual elements reflected her own negotiations between her artistic practice and the expectations of her religious faith.

![]()

![]() [Figure 6] Hamidah Jalil. Hampatong #1. 1995.

Acrylic on canvas. 76 x 92cm. Image credit: Nurdiana Rahmat.

[Figure 7] Hamidah Jalil. Hampatong #5.

1997. Acrylic on canvas. 51 x 66cm. Image credit: Moving On: An Art Exhibition

of Small Works by members of APAD, published by Angkatan Pelukis Aneka Daya

(Association of Artists of Various Resources, APAD), 2013, Pg. 20.

[Figure 6] Hamidah Jalil. Hampatong #1. 1995.

Acrylic on canvas. 76 x 92cm. Image credit: Nurdiana Rahmat.

[Figure 7] Hamidah Jalil. Hampatong #5.

1997. Acrylic on canvas. 51 x 66cm. Image credit: Moving On: An Art Exhibition

of Small Works by members of APAD, published by Angkatan Pelukis Aneka Daya

(Association of Artists of Various Resources, APAD), 2013, Pg. 20.

While Islam discouraged the depictions of figurative forms in works of art, Hamidah was adept at separating this prohibition from her art making practices. She worked around these boundaries by incorporating an audience-specific strategy into her practice and in the way she presented or promoted her work. That strategy included ‘not selling these (figurative forms) for the Malay or Muslim market).’40 This did not hamper her artistic creativity as she believed, ‘for me, to draw Hampatong is also.... whatever movement you draw from the colour to the canvas is from the work of Allah ta'allah. He gave you the movement. He gave you the thing... to think... to color to.... match whatever color to put on the canvas, and it's from amanah... it's from yourself. So, it's a rezeki (blessing).’41

Hamidah became a member of APAD shortly after she took up painting and exhibited in the society’s annual exhibitions from 1995 through 2014. In 2003, with the support of then-president of APAD, Rahman Rais, Hamidah collaborated with eight other female members of APAD—Fazelah Supaat Abas, Irda Haeryati Tomin, Juliana Yasin, Nuradiah Ali, Rauzanah Saini, Siti Zurianah Sanwari, Surina Mohamed Sani and Ye Ruoshi—to organise the society’s first all-female exhibition; an unprecedented landmark for the society. There are no records of a follow-up, all-female exhibition in the years after 2003.42

Nochlin suggested the usefulness of exploring the roles that the more prominent male artists played in the professional development of women artists. By understanding the creative dynamics between Hamidah and her late husband, one could begin to understand why her focus has changed towards the selling and promotion of his work after his passing in 2007. Through her husband’s network of support, she exhibited in group shows organised by various artist collectives and societies. In 1995, she exhibited with her husband, Mohammad Din Mohammad, who was one of the members of the organising art group, Culture Colour Connections, at the Fremantle Arts Centre in Perth, Australia [Figure 8].43 She maintains in close contact with one of the members of Culture Colour Connections, Abu Jalal Sarimon, today. Jalal continues to reach out to her with exhibition opportunities in Singapore and overseas. From this example, it becomes clear that Hamidah Jalil’s collaborations with her husband were key factors in her artistic development.

Hamidah shared with me in an interview that while she still made art, she was no longer as active as before due to her full-time job as a healing practitioner. With the support of her family, she was shifting her focus toward materialising her dream of organising a solo exhibition of her late husband’s artworks at a national institution in Singapore. With an unwavering spiritual and mental balance that she has achieved for herself, Hamidah was able to negotiate and co-exist around the invisible lines and boundaries that marked her position as an artist, a wife and mother.

![]() [Figure 8] Hamidah Jalil. Hampatong #2.

1995. Acrylic on canvas. 76 x 92cm. Image credit: Culture Colour Connection

exhibition catalogue, published by Culture Colour Connection and Fremantle Arts

Centre, 1998, Pg. 14.

[Figure 8] Hamidah Jalil. Hampatong #2.

1995. Acrylic on canvas. 76 x 92cm. Image credit: Culture Colour Connection

exhibition catalogue, published by Culture Colour Connection and Fremantle Arts

Centre, 1998, Pg. 14.

Conclusion

Women artists, regardless of where they come from, shared the experience of having to navigate the multiplicities of their identities as women, artists, self-promoters, wives, mothers and so on, especially in the second half of the twentieth century.

By tracing the artistic development and practices of Rohani Ismail, Hamidah Suhaimi, Rosma Mahyuddin Guha, Maisara (Sara) Dariat and Hamidah Jalil, this study has provided an understanding of the challenges and barriers that Singapore Malay women artists faced in their artistic practices and how they affected their positions in the Singapore art ecosystem.

Probing into the history of Angkatan Pelukis Aneka Daya (Association of Artists of Various Resources, APAD), this article followed the development of these artists and their contributions to Singapore’s art history. Their collective experiences revealed that their conditions of making art had contributed to the decline of their artistic activities.

Religion, ethnic and cultural identities influenced the way that Singapore Malay women developed and presented their work in the modern and contemporary period. Hamidah Jalil is continuing her artistic approach as a Muslim woman, and dedicate her time and efforts to promote her husband late Mohammad Din Mohammad to museums and arts institutions. Her balance in managing between her identities as a Muslim, a mother, a wife and an artist, had allowed her to come to terms with her own expectations as a professional artist.

In the case of Rosma Guha, her artistic contributions remained overlooked by the institutions of art history despite having been active in the exhibition circuit for most of her artistic career. By conducting an analysis of her work through Roszika Parker and Griselda Pollock’s strategy of feminist interventions, this study has argued that the hegemonic masculinity in the institutions of art history has cultivated the inability to read her work through a more critical lens.

Rohani Ismail, Hamidah Suhaimi and Sara Dariat’s contributions in the formative years of Angkatan Pelukis Aneka Daya (Association of Artists of Various Resources, APAD), as well as records of Malay female students in Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts during the period of the 1960s through 1980s, revealed Malay women artists participated and were involved in art production throughout the course of Singapore’s modern art history.

When art history was institutionalised during the 1990s, particularly after museums such as Singapore Art Museum were established, records of Malay women artists’ contributions seemed to have been completely erased. Given the shift towards exhibition making in the local art historical landscape at the turn of the twenty-first century, it is therefore important for curators to study closely and question existing narratives circulated by arts institutions and widely consumed by the public. By re-examining their research biases, there can be great collective efforts done to recover contributions made by artists whose voices may have been forgotten or overlooked.

The paucity in critical research and writing on Singapore Malay women artists have contributed to the consistent exclusion of their contributions to significant “canon-making” projects. Given the extremely small representation of Singapore Malay women artists in both the communities of Malay and women artists in Singapore, I have real concerns on whether these consistent exclusions have contributed to the complete erasure of their contributions in the widely consumed art historical narratives in Singapore. As members of the local art ecosystem, art historians, curators and art educators should be ready to reject systems of evaluation implicated by structural racism and gender biases, especially when these systems are used to inform their own selection criteria to their exhibition or publication projects.

Inserting a Malay woman artist (or two) into a publication or exhibition project may not reflect an intersectional approach to curatorial research. In an interview with Salleh Japar, artist-curator and APAD member, he shared the importance for Singapore curators today to shed their bias and apply a grassroots approach to their curatorial practice by supporting and mentoring art graduates or underrepresented artists.44

This article has highlighted key artistic contributions by Malay women artists who have been rendered invisible in Singapore’s art historical economy. Adopting the approach of intersectional feminist intervention to the study of women artists in Singapore, I have provided a more diverse and richer account of artistic contributions and their impact in the local art landscape. I have also offered a more inclusive approach to the current scholarship of women artists in Singapore and provided broader research directions for the study of the artistic practices of Singapore Malay artists.

By exploring art making experiences of three significant artists and some of the key challenges they have faced, I have argued that Singapore Malay women artists successfully developed their own terms and conditions in their artistic practices through working around the challenges encountered in their art making experiences. Even if this means coming to terms with the fact that their artistic practice were perceived as nothing more than a hobby in view of personal commitments.

Notes:

1. National Arts Council, “A Note on the Publication,” in Singapore’s Visual Artists (Singapore: National Arts Council, 2016), 1.

2. Further comparisons shows this number to comprise less than three percent of women artists featured (Chinese artists at almost eighty percent).

3. Rosihan Dahim, “Malay women artists left out,” The Straits Times, 2 July 2011, 6.

4. Bridget Tracy Tan, Women Artists in Singapore (Singapore: Select Publishing, 2011), 108-109. When the book was published, it was written that Neng “does not draw much anymore” and instead, was focused in managing her own design company. There were no indications whether her work was “collected by national institutions”. However, Neng’s artistic practice which involved negotiation with materials, forms and spaces categorises her with other artists whom Tan clustered this chapter of her book.

5. Bridget Tracy Tan, Women Artists in Singapore(Singapore: Select Books, 2011), 9.

6. Tan, Women Artists in Singapore (Singapore: Select Books, 2011), 7.

7. Kimberle Crenshaw, "Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics," University of Chicago Legal Forum 1989, no. 1 (December 2015): 167, https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8.

8. For this study, “Malay” will be referred to as an ethnicity instead of a racial profile, as it emphasises the multiplicities of Malay identities that can be applied from post-independent Singapore to the present time. Hence, “Singapore Malay women artists” will refer to artists who identify as women and have established an artistic practice, as well as produced artistic work in the visual arts of painting, photography, sculpture, performance and the multi-disciplinary forms of art installation work in Singapore, and who significantly connect with both their ethnic Malay and Singaporean identities through the practice of language and cultural traditions. Artists mentioned in this study will be referred to by their first, full or preferred professional names. Unless otherwise stated, surnames are not applicable to Malay names.

9. Linda Nochlin, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” ARTnews 69, no. 9 (January 1971): 22–39, 67–71.

10. Yvonne Low, “Becoming professional artists in postwar Singapore and Malaya: Developments in art during a time of political transition,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 46, no. 3 (October 2015): 470, http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S002246341500034X.

11. Yvonne Low, “A “Forgotten” Art World: The Singapore Art Club and its Colonial Women Artists” in Charting Thoughts: Essays on Art in Southeast Asia, ed. Low Sze Wee and Patrick D. Flores (Singapore: National Gallery Singapore, 2017), 106. The Singapore Art Club started as a private club and flourished into an open club from 1883. Its activities continued for 60 years before it ceased operation during the Japanese Occupation.

12. Abdul Rahman Rais, “Foreword,” in Our Pioneer Artists: Malay Visual Art Practice from Post-War Period (Singapore: Angkatan Pelukis Aneka Daya, 2013), 2.

13. “Anggota wanita pertama Apad,” Berita Harian, March 3, 2013, 11. All texts from Berita Harianare in Malay and translated by the author.

14. Abdul Ghani Hamid, An Artist’s Note (Singapore: Angkatan Pelukis Aneka Daya, APAD, 1991), 13.

15. Sulaiman Jeem, “Angkatan Pelukis Aneka Daya…,” Berita Minggu, August 12, 1962, 6.

16. “Malay artists encouraged,” The Straits Times, December 27, 1963, 4.

17. Abdul Ghani Hamid, “Pameran 1963,” in Pameran (Singapore: APAD, 1992), 10. All original texts in this book are in Malay and translated by the author.

18. “Sa-bagai Pinang Di-belah Dua,” Berita Harian,May 22, 1963, 7.

19. Mei-Lin Chew, “Women artists show their colours,” The Straits Times, June 24, 1975, 10.

20. “Puan Hamidah Suhaimi dengan portret2-nya,” Berita Harian, August 31, 1965, 14.

21. Linda Boersma and Patrick Van Rossem, “Rewriting or Reaffirming the Canon? Critical Readings of Exhibition History – Editorial,” Stedelijk Studies Issue #2 (Spring 2015), accessed on March 29, 2020. https://stedelijkstudies.com/journal/rewriting-or-reaffirming-the-canon-criticalreadings-of-exhibition-history.

22. Seng Yiu Jin, “Framing Contemporary Art in Southeast Asia through Exhibitionary Discourse,” in Southeast Asia: Spaces of the Curatorial, eds. Ute Meta Bauer and Brigitte Oetker (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2016), 66.

23. National Arts Council, “A Note on the Publication,” in Singapore’s Visual Artists(Singapore: National Arts Council, 2016), 1.

24. Helvi L. Sipilä, “Women’s lib; 30 years of progress,” The UNESCO Courier(March 1975): 4, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000074836.

25. Mei-Lin Chew, “Women artists show their colours,” The Straits Times, June 24, 1975, 10.

26. Zawiyah Salleh, “Dari seorang pemberita kepada pelukis,” Berita Harian, November 19, 1974, 4. This article writes about Sara’s development from a journalist to a batik painter. While she shared that she learned batik from “veteran artists”, it was unclear who these artists were.

27. Gene Teo, “Wide range of works by 23 artists to go on display,” New Nation, December 15, 1973, 11.

28. Abdul Ghani Hamid, “Sara kemukakan ‘percubaan’ sulungnya yg berpotensi,” Berita Harian, November 10, 1974, 13. Original text in Malay and translated by the author.

29. Zawiyah Salleh, “Dari seorang pemberita kepada pelukis,” Berita Harian, November 19, 1974, 4. Original text in Malay and translated by the author.

30. It was reported in Berita Harian (3 March 2013) that she has Parkinsons. The author made contact with the artist on 11 March 2020, and understands that she has stopped painting as her condition has gotten severe.

31. Koh Siew Tin, “Family patterns,” The Straits Times, October 5, 1989, 3.

32. Other art educational institutions, such as Baharuddin Vocational Institute and LASALLE College of the Arts, only started in 1965 and 1986, respectively.

33. T. Sasitharan, “On the path to Discovery,” The Straits Times, December 3, 1988, 5.

34. “Flowers and dragon dance hold sway over Mrs Choonhavan,” The Straits Times, July 26, 1975, 6.

35. Refer to Janet Chew’s articles, “Watercolours made easy” and “Painting a portrait”, dated 9 May 1989 and 31 October 1989, respectively. Chew referred to Rosma Guha as a “freelance artist” in her introductions.

36. The Grand Discovery: Art Exhibition, (Singapore: Shell Art Exhibition, 1991), Exhibition catalogue.

37. Griselda Pollock, Vision and Difference (New York: Routledge, 1988), 15. Pollock has described art history as a series of “representational practices which actively produce definitions of sexual difference and contribute to the configuration of sexual politics and power relations”.

38. Linda Nochlin, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” ARTnews 69, no. 9 (January 1971): 22–39, 67–71.

39. Hamidah Jalil (artist), in discussion with Nurdiana Rahmat at artist’s residence, March 12, 2020.

40. Interview with Hamidah Jalil (artist) at artist’s residence, March 12, 2020.

41. Interview with Hamidah Jalil (artist) at artist’s residence, March 12, 2020.

42. Interview with Hamidah Jalil (artist) at artist’s residence, March 12, 2020. See Appendix 1, Pg 95. In this interview, Hamidah shared that the idea of this exhibition was mooted by Rahman Rais. The female members organised the exhibition while the Executive Committee secures a venue. Hamidah also shared the dynamics of the society changed after the succession of a new generation of artists. Her activity with APAD slowed down after 2013, and she was unable to share more details of her experiences with the society after this period.

43. Culture Colour Connection, (Perth: Culture Colour Connection, 1995), Exhibition catalogue.

44. Interview with Salleh Japar (artist and art educator at LASALLE College of the Arts) at LASALLE College of the Arts, February 24, 2020.

About the contributor: Nurdiana Rahmat has more than ten years of experience in developing and implementing public programmes for museums. As an independent researcher, her research and exhibition projects include Yukiharu Furuno: Inspirations from the Blue (2017) and inVISIBLE: Exploring and Redefining Femininity Through Batik (2018). She is currently an arts manager at National Gallery Singapore where she develops interactive art installations for children. Her latest projects include Gallery Children’s Biennale (2019) and Small Big Dreamers (2018; 2020). She received an MA in Asian Art Histories from LASALLE College of the Arts with her thesis titled, Terms and Conditions: Singapore Malay Women Artists and Their Art Making Experiences. Her research interests includes women artists and intersectional feminist art histories.Rosma Guha’s last public appearance as a visual artist was in APAD’s exhibition, Our Pioneer Artists: Malay Visual Art Practices from Post-War Period in 2013. Despite her contributions to the local art scene and meeting the selection criteria which informed both Bridget Tracy Tan’s Women Artists in Singapore (2011) and National Arts Council’s Singapore’s Visual Artist (2016), Rosma Guha was still excluded from these projects.

Apart from local newspaper reports, there has been little research and writing conducted on Rosma Guha’s work and practice despite her prolific work from the 1980s to the 2010s. Was it also possible that Rosma Guha’s exclusion was abetted by the very system that supported her artistic endeavours? This perception was drawn from the fact that the institutions of art themselves, including in Singapore, were deeply gendered.37 In contemporary art, works that addressed critical socio-political events or engaged critically with historical references appear to be at the foreground of the art historical writings and discourse. Therefore, it may also be possible that Rosma Guha’s work was overlooked based on the subject matter of her paintings alone.

Two of Rosma Guha’s works did feature in the canonical catalogue Singapore Fine Arts Index 1998 by Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts: Array of Orchids and Pak Tani. In Array of Orchids [Figure 4], she demonstrated her adept abilities as a colourist, through her use of selection of colours that created a visual harmony, balancing the purple and white orchids against the shades of green foliage. Her arrangement of these colours was intentional, as they provided a natural frame for the white orchids to stand out in this work. She executed a smooth variegated wash to set the background and showcased a remarkable glazing technique in the floral petals. Her proficient use of colour washes created meaningful depths and shadows to the scene, demonstrating proficient control in one of fine art’s most unforgiving mediums.

In a rare portraiture work, Pak Tani [Figure 5], Rosma Guha demonstrated the range of her techniques as a skilled watercolour artist. Her expert control of the brush to apply the technique of negative painting gave a natural sense of light and environment. The different contours of colour shading created a clever composition of positive and negative spaces to give a sense of three-dimensional depth in this watercolour painting. Similar to An Array of Orchids, she played with lines to add realistic details to her subject’s facial expression, adding a nuanced sense of time to this static painting. She also applied just the right amount of cooler purple tones to give an otherwise neutral painting a subtle pop of colour to attract one’s eyes.

In watercolour paintings, varying depictions of Singapore’s landscapes such as the ubiquitous Singapore River or streets scenes with shophouses by her male contemporaries were highly lauded and recognized in Singapore’s art historical canon. It must be recognised that Rosma Guha’s focus on flowers further demonstrated her negotiations of space in the watercolour medium to create her own distinct subject matter and therefore, highlighted her unique standing as a talented watercolour artist.

Exploring the Intersections in Hamidah Jalil’s Hampatong series

Nochlin pointed out that one of the most common observations of women artist in the later part of the nineteenth and into the twentieth century was that most of them have or have had close connections to a more prominent male artistic personality.38 By applying this observation to Singapore Malay women artists, this article has highlighted the shared connections that some of these artists have as ‘artists’ wives’ or members of an art collective or society. While they may receive support to present their work, it was challenging for them to consistently participate in exhibitions and remain active in the local art ecosystem.

Hamidah Jalil is a self-taught artist who primarily works in the medium of painting. She started her artistic practice in the early 1990s, prompted by an unconventional dare made by her late husband, artist Mohammad Din Mohammad, after she gave a critique of his work.39 Working mostly with acrylic, Hamidah’s close connections with her Javanese roots, and Java’s position within the larger context of the shared traditions and cultures of the Nusantara, or the Malay Archipelago, informed the way she applied colours, patterns and styles in her painted works. She recalled that when she created her first painting, she had an image of a favourite batik print pattern in mind, and then started to develop that image further on canvas.

Hamidah’s earlier abstract style changed to more figurative forms when she created the first work from her Hampatong series in 1995 [Figure 6]. This series of eight paintings was created between 1995 and 1998 and the name Hampatong, was a play on the words ‘Hamidah’s patong (dolls)’. In this series, she created a central figure, or two characters, in the case of Hampatong V (1997) [Figure 7], framed by an assembly of patterns, which she drew from several indigenous cultures. She maintained a balance of earthy and vibrant tones by employing strong lines to accentuate and control the composition of colours. This balance of varying visual elements reflected her own negotiations between her artistic practice and the expectations of her religious faith.