这是妈妈. 这是爸爸.: an experiment in translation

Kezia Yap

To cite this contribution: Yap, Kezia. ‘这是妈妈. 这是爸爸.: an experiment in translation’. Currents Journal, Archipelagic Encounters (2021), https://currentsjournal.net/an-experiment-in-translation.

Download this article ︎︎︎PDF

Keywords:

Translation; Chinese identity; composition; biculturality; Asian-Australian; interdisciplinary practice

Abstract:

这是妈妈. 这是爸爸. is an interdisciplinary work and creative translation of two simple Chinese sentences to orchestral music of Western classical tradition. Stemming from broader explorations of Asian-Australian identity and its intersections with interdisciplinary practice, this paper interrogates the experimental strategy used to connect with my Chinese heritage and better understand my own bicultural identity as it mirrors the positioning of my practice as an interdisciplinary artist and composer.

Using frameworks of identity, translation, and Chinese diaspora theory, this paper proposes translation as a means through which to establish identity. The process of translation is outlined, elaborating on the methods developed to challenge my compositional practice, which included mapping linguistic characteristics to musical attributes, and using text as a spatial guide for structuring musical content.

Drawing on visual and interdisciplinary approaches to composition, the paper explores implications of the work when viewed through the lens of various forms. Critical discussion outlines the various and simultaneous success and failure of the work when considered as a translation and as a strategy for establishing identity, presenting 这是妈妈. 这是爸爸. as a unique articulation of the Asian-Australian experience.

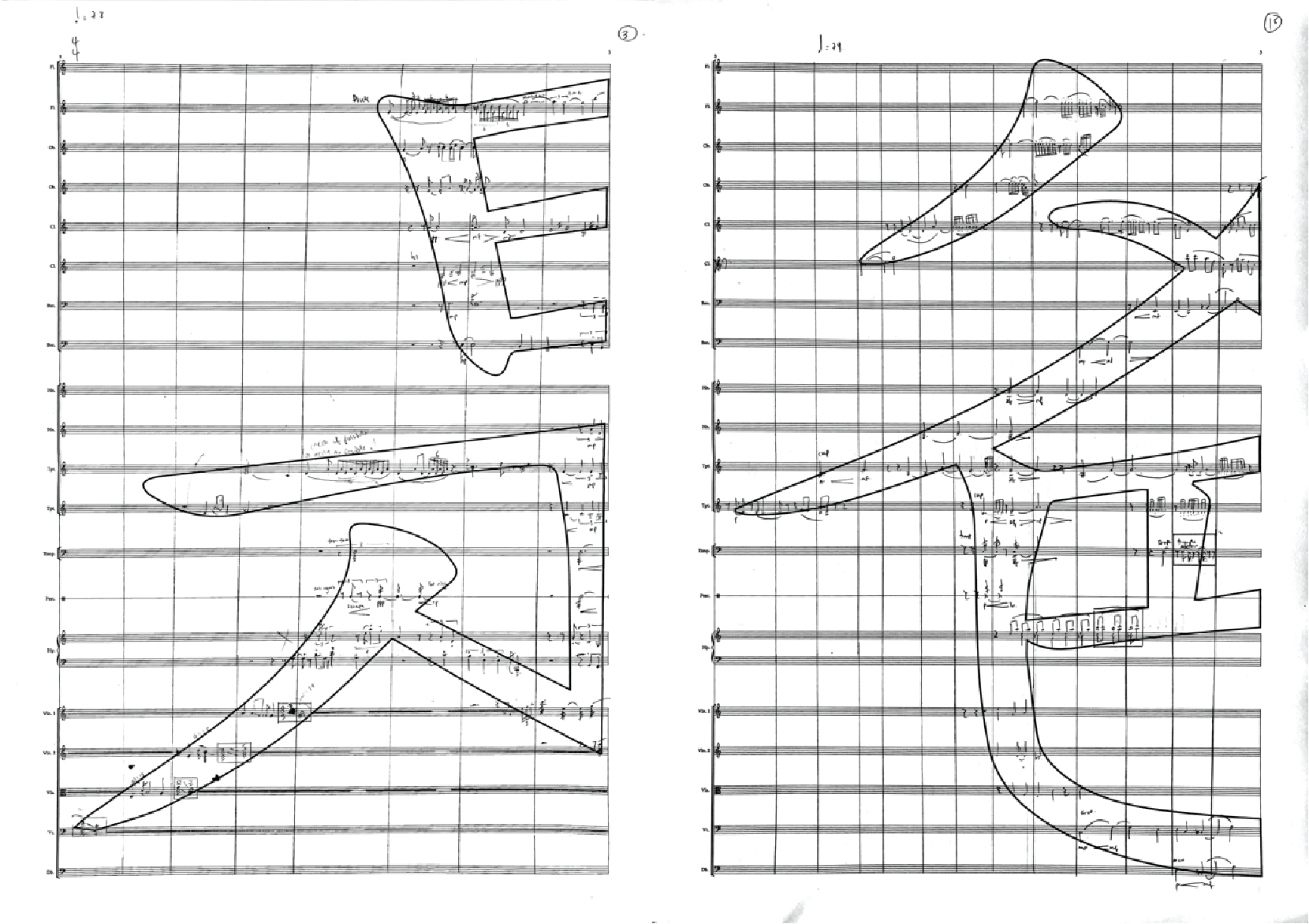

[Figure 4] Kezia Yap, image example of an

excerpt of handwritten score within the shape of overlaid text, with rhythms

generated through the transcription of the sound of writing this character

[Figure 4] Kezia Yap, image example of an

excerpt of handwritten score within the shape of overlaid text, with rhythms

generated through the transcription of the sound of writing this character [Figure 1] Kezia Yap, image of the draft

translation or musical score

[Figure 1] Kezia Yap, image of the draft

translation or musical score

这是妈妈. 这是爸爸. is a translation. More specifically,

it is an attempt to translate Chinese into music. If we consider Western

classical music abstractly as language with tones, phrases, syntax and a

written script in the form of notation, then as an artist and composer, I am

fluent in that language. Music is a practice that I have chosen to pursue and locate

myself within—I have undertaken years of lessons in

piano, composition and music theory, attended a music conservatorium for

tertiary education and I continue to practice music to this day. As the basis

of my artistic practice, music is second nature to me and I would consider it to

nearly be my native tongue. Conversely, Chinese is the intrinsic language of my

cultural heritage that I do not read, write or speak.

As an Asian-Australian with Chinese heritage, my lack of language is something that has distanced me from the culture of my family and created barriers that impede my search for connections to a culture that is expected of me. In On Not Speaking Chinese (2001), Ien Ang equates the lack of language of Chinese diasporic individuals (particularly in Western countries) with a lack of authenticity underlying their Chinese identity, from the perspective that “authenticity” is defined as an adherence to the stereotypical expectations of a person originating from China.1 Drawing on her own experiences, Ang writes ‘“not speaking Chinese”, therefore, has become a personal political issue to me, an existential condition which goes beyond the particularities of an arbitrary personal history. It is a condition that has been hegemonically constructed as a lack, a sign of loss of authenticity.’2

While the term ‘Asian-Australian’ may flatten the depth and breadth of diasporic experience, I use the term to express and emphasise the shared nature of experiences like my own. Like me, many Asian-Australians often cite an irretrievable distance between themselves and their respective cultures, especially after many years of trying to assimilate into Australia’s dominant Western culture. Eventually they find themselves oscillating between two or more cultures. However, from the context of my own experience, it is important to acknowledge the complex position of being Asian-Australian with a heritage traced from Australia, through South-East Asia (in particular, Malaysia) and back to China. While my heritage presents many political implications it also correlates with Ang’s notion that the idea of ‘Chineseness’ and the Chinese identity remains slippery and indeterminate. She proposes that ‘Chineseness is a category whose meanings are not fixed and pregiven, but constantly renegotiated and rearticulated, both inside and outside China.’3 With this in mind, and as I try to understand and locate my own identity within the scope of Chineseness, I must acknowledge that my Chinese identity is in a constant state of flux, and is thus full of latent potential that continues to provide interesting perspectives and insights.

In response to this personal lived experience of in-betweenness, or as Ang proposes, within the ‘creative tension of “where you’re from” and “where you’re at”’,4 my creative research is increasingly engaged with unlocking new ways that I might explore my own Asian-Australian experience. Consequently, this project represents part of an ongoing attempt to activate meaningful connections through the framework of my experiences as a both a bicultural and transnational individual.

Drawing on Stuart Hall’s conception of identity, which Ang rearticulates as ‘a strategy to open up avenues for new speaking trajectories, the articulation of new lines of theorising’,5 this research seeks to establish an identity as a framework that opens new trajectories for giving voice to the self. In addition, composer Tōru Takemitsu describes that for the composer: ‘self-realisation is the writing of words in sound.’6 Thus, the multiple potentials of my heritage-in-flux evokes an identity framework ‘for new speaking trajectories’, which viewed alongside Takemitsu’s understanding of the composer, motivates a process of music and language-based translation as a means to establish identity.

Translation is rich and generous in its potential to produce new perspectives and ideas—as Salman Rushdie has described: ‘it is normally supposed that something always gets lost in translation; I cling, obstinately, to the notion that something can also be gained.’7 Ang positions Rushdie’s quote in relation to the creative potentials that can be generated from the space in-between ‘where you’re from’ and ‘where you’re at’8 and also utilises translation as a device through which to understand the diasporic experience.9 In addition to this, other artists have engaged with notions of translation in their creative practices. Notably, and in relation to my own project and its use of music, Mia Salsjö’s Modes of Translation (2016)10 is significant as it deals with concepts of translation in a musical context. While Salsjö’s work translates space and architecture into sound through processes of rigorous linguistic code-based systems, my project engages with the translation of text into music. In particular, my project seeks to experiment with translation as a method through which to establish, enrich and make sense of a cultural identity that often feels ambiguous and contested. In The Translator’s Invisibility (2018),translation theorist Lawrence Venuti describes the slippery nature of meaning in text, stating that ‘meaning is a plural and contingent relation, not an unchanging unified essence, and therefore a translation cannot be judged according to mathematics-based concepts of semantic equivalence or one-to-one correspondence.’11 Translations are an interpretation, whose meanings are influenced by the social and cultural context of its translator and audience. With this in mind, and with myself positioned as the translator drawing on my own lived experience, my project seeks to offer a unique articulation of an aspect of the Asian-Australian experience.

Making and Composing

This project emerged from a place of personal experience and meaning. I used the two very basic sentences that I know how to say in Mandarin as a starting point, and as text to be translated:

这是妈妈. 这是爸爸.12

In seeking to produce a translation, but more importantly, to translate, a process needed to be established. This process expanded on my current practice in working with music (or composing) and thus necessitated experimentation with different creative approaches and methods. By breaking away from the ways of making with which I was already comfortable, I hoped to activate and speculate upon new possibilities.

I initially started working with the Mandarin dialect, hoping that its tonal nature13 would connect in some ways to music and lend to more instinctive methods that could be used for translation. Despite its initial appeal, my experiments in transcribing speech as music did not produce creatively fulfilling results, and my process turned towards more abstract methods of mapping and musical content generation. I used recognisable attributes of the language, such as linguistic tones and characters, and then emphasised abstract qualities, such as, the rhythms produced through the act of writing. Through this process I developed a palette of raw materials that I could map to musical parameters including pitch, rhythm, texture, timbre and dynamics. By mapping the words or characters to these musical parameters I was able to code the sentences with certain sounds and put limitations on the way that the translation was generated.

Generative music, or music created through generative processes, is an already existing practice that seeks to creatively interpret data in rich and meaningful ways. In fact, other composers have similarly sought to explore the potentials for generating music from Chinese language and calligraphy, such as Silvio Ferragina.14 While Ferragina’s practice establishes generative techniques based on calligraphic strokes and gestures,15 this project sought to combine a range of mappings or generative techniques with other, more visual or material-based approaches to form intricate layers of micro-translations that weave together and contribute to the work and translation as a whole.

![]() [Figure 2] Kezia Yap, image of a table

mapping characters to musical gestures, timbre and dynamics

[Figure 2] Kezia Yap, image of a table

mapping characters to musical gestures, timbre and dynamics

Another key method that was used in the translating process was considering text and music as visual and physical material (rather than alluding to musical or textual meaning) and transferring the physicality of the text to the score. By approaching the process in this way, I departed from my own established and conventional methods of musical composition and moved towards broader ways of composing and interdisciplinary approaches to process of translation. The process of this work moved into a somewhat ambiguous and intermedial space as I tried and tested alternative methods and approaches to making/composing. The text was transferred onto the score by overlaying digitally-rendered images of the text on an empty manuscript formatted for the orchestra (with each character spread over two A3-sized pages). Overlaying the text over the score was a means to create structured visual outlines that I could “colour-in” or populate with musical content, generating certain sonic textures or instrumental combinations. Put another way, the physical body of the text dictated what and when instruments would play (as the score is read from left to right across time), as well as a structure that determined where mappings could be applied. For example, I used the rhythms generated from the act of writing the 妈 character in the string parts in the following image, written inside the outlines of the 妈 character. Using this method of populating the score with musical content enabled the work to emerge in a more considered and structured way.

![]() [Figure 3] Images of

instrumental combinations with corresponding characters

[Figure 3] Images of

instrumental combinations with corresponding characters

When considering methods of making that use text and music as visual and physical material, it is perhaps important to acknowledge the insightful discussions surrounding notions of negative or empty space as it manifests across forms and disciplines. For example, comparisons could be drawn between kōng bái (空白literally translating from Chinese to ‘blank space’) in Chinese calligraphic art and paintings and the use of silence in music (notated through rests); and similarly, the Japanese concept of mā (間 literally translating from Japanese to time, pause, space, room)16 as understood through Takemitsu’s A Single Sound (1995) in which he equates mā to silence.17

As an Asian-Australian with Chinese heritage, my lack of language is something that has distanced me from the culture of my family and created barriers that impede my search for connections to a culture that is expected of me. In On Not Speaking Chinese (2001), Ien Ang equates the lack of language of Chinese diasporic individuals (particularly in Western countries) with a lack of authenticity underlying their Chinese identity, from the perspective that “authenticity” is defined as an adherence to the stereotypical expectations of a person originating from China.1 Drawing on her own experiences, Ang writes ‘“not speaking Chinese”, therefore, has become a personal political issue to me, an existential condition which goes beyond the particularities of an arbitrary personal history. It is a condition that has been hegemonically constructed as a lack, a sign of loss of authenticity.’2

While the term ‘Asian-Australian’ may flatten the depth and breadth of diasporic experience, I use the term to express and emphasise the shared nature of experiences like my own. Like me, many Asian-Australians often cite an irretrievable distance between themselves and their respective cultures, especially after many years of trying to assimilate into Australia’s dominant Western culture. Eventually they find themselves oscillating between two or more cultures. However, from the context of my own experience, it is important to acknowledge the complex position of being Asian-Australian with a heritage traced from Australia, through South-East Asia (in particular, Malaysia) and back to China. While my heritage presents many political implications it also correlates with Ang’s notion that the idea of ‘Chineseness’ and the Chinese identity remains slippery and indeterminate. She proposes that ‘Chineseness is a category whose meanings are not fixed and pregiven, but constantly renegotiated and rearticulated, both inside and outside China.’3 With this in mind, and as I try to understand and locate my own identity within the scope of Chineseness, I must acknowledge that my Chinese identity is in a constant state of flux, and is thus full of latent potential that continues to provide interesting perspectives and insights.

In response to this personal lived experience of in-betweenness, or as Ang proposes, within the ‘creative tension of “where you’re from” and “where you’re at”’,4 my creative research is increasingly engaged with unlocking new ways that I might explore my own Asian-Australian experience. Consequently, this project represents part of an ongoing attempt to activate meaningful connections through the framework of my experiences as a both a bicultural and transnational individual.

Drawing on Stuart Hall’s conception of identity, which Ang rearticulates as ‘a strategy to open up avenues for new speaking trajectories, the articulation of new lines of theorising’,5 this research seeks to establish an identity as a framework that opens new trajectories for giving voice to the self. In addition, composer Tōru Takemitsu describes that for the composer: ‘self-realisation is the writing of words in sound.’6 Thus, the multiple potentials of my heritage-in-flux evokes an identity framework ‘for new speaking trajectories’, which viewed alongside Takemitsu’s understanding of the composer, motivates a process of music and language-based translation as a means to establish identity.

Translation is rich and generous in its potential to produce new perspectives and ideas—as Salman Rushdie has described: ‘it is normally supposed that something always gets lost in translation; I cling, obstinately, to the notion that something can also be gained.’7 Ang positions Rushdie’s quote in relation to the creative potentials that can be generated from the space in-between ‘where you’re from’ and ‘where you’re at’8 and also utilises translation as a device through which to understand the diasporic experience.9 In addition to this, other artists have engaged with notions of translation in their creative practices. Notably, and in relation to my own project and its use of music, Mia Salsjö’s Modes of Translation (2016)10 is significant as it deals with concepts of translation in a musical context. While Salsjö’s work translates space and architecture into sound through processes of rigorous linguistic code-based systems, my project engages with the translation of text into music. In particular, my project seeks to experiment with translation as a method through which to establish, enrich and make sense of a cultural identity that often feels ambiguous and contested. In The Translator’s Invisibility (2018),translation theorist Lawrence Venuti describes the slippery nature of meaning in text, stating that ‘meaning is a plural and contingent relation, not an unchanging unified essence, and therefore a translation cannot be judged according to mathematics-based concepts of semantic equivalence or one-to-one correspondence.’11 Translations are an interpretation, whose meanings are influenced by the social and cultural context of its translator and audience. With this in mind, and with myself positioned as the translator drawing on my own lived experience, my project seeks to offer a unique articulation of an aspect of the Asian-Australian experience.

Making and Composing

This project emerged from a place of personal experience and meaning. I used the two very basic sentences that I know how to say in Mandarin as a starting point, and as text to be translated:

这是妈妈. 这是爸爸.12

In seeking to produce a translation, but more importantly, to translate, a process needed to be established. This process expanded on my current practice in working with music (or composing) and thus necessitated experimentation with different creative approaches and methods. By breaking away from the ways of making with which I was already comfortable, I hoped to activate and speculate upon new possibilities.

I initially started working with the Mandarin dialect, hoping that its tonal nature13 would connect in some ways to music and lend to more instinctive methods that could be used for translation. Despite its initial appeal, my experiments in transcribing speech as music did not produce creatively fulfilling results, and my process turned towards more abstract methods of mapping and musical content generation. I used recognisable attributes of the language, such as linguistic tones and characters, and then emphasised abstract qualities, such as, the rhythms produced through the act of writing. Through this process I developed a palette of raw materials that I could map to musical parameters including pitch, rhythm, texture, timbre and dynamics. By mapping the words or characters to these musical parameters I was able to code the sentences with certain sounds and put limitations on the way that the translation was generated.

Generative music, or music created through generative processes, is an already existing practice that seeks to creatively interpret data in rich and meaningful ways. In fact, other composers have similarly sought to explore the potentials for generating music from Chinese language and calligraphy, such as Silvio Ferragina.14 While Ferragina’s practice establishes generative techniques based on calligraphic strokes and gestures,15 this project sought to combine a range of mappings or generative techniques with other, more visual or material-based approaches to form intricate layers of micro-translations that weave together and contribute to the work and translation as a whole.

[Figure 2] Kezia Yap, image of a table

mapping characters to musical gestures, timbre and dynamics

[Figure 2] Kezia Yap, image of a table

mapping characters to musical gestures, timbre and dynamicsAnother key method that was used in the translating process was considering text and music as visual and physical material (rather than alluding to musical or textual meaning) and transferring the physicality of the text to the score. By approaching the process in this way, I departed from my own established and conventional methods of musical composition and moved towards broader ways of composing and interdisciplinary approaches to process of translation. The process of this work moved into a somewhat ambiguous and intermedial space as I tried and tested alternative methods and approaches to making/composing. The text was transferred onto the score by overlaying digitally-rendered images of the text on an empty manuscript formatted for the orchestra (with each character spread over two A3-sized pages). Overlaying the text over the score was a means to create structured visual outlines that I could “colour-in” or populate with musical content, generating certain sonic textures or instrumental combinations. Put another way, the physical body of the text dictated what and when instruments would play (as the score is read from left to right across time), as well as a structure that determined where mappings could be applied. For example, I used the rhythms generated from the act of writing the 妈 character in the string parts in the following image, written inside the outlines of the 妈 character. Using this method of populating the score with musical content enabled the work to emerge in a more considered and structured way.

[Figure 3] Images of

instrumental combinations with corresponding characters

[Figure 3] Images of

instrumental combinations with corresponding charactersWhen considering methods of making that use text and music as visual and physical material, it is perhaps important to acknowledge the insightful discussions surrounding notions of negative or empty space as it manifests across forms and disciplines. For example, comparisons could be drawn between kōng bái (空白literally translating from Chinese to ‘blank space’) in Chinese calligraphic art and paintings and the use of silence in music (notated through rests); and similarly, the Japanese concept of mā (間 literally translating from Japanese to time, pause, space, room)16 as understood through Takemitsu’s A Single Sound (1995) in which he equates mā to silence.17

In this essay, Takemitsu posits that richness in music is created through the

interactions and confrontations between silence and sound. He states ‘this mā, its powerful silence, is

that which gives life to the sound and removes it from its position of primacy.’18 Silence is understood as music

within the ontological sensorial experience of the orchestral context. It is

the strategic use of rests and the silence that allows us to hear and

consequently recognise orchestral music by creating delicate balances of sound that

contribute to a rich and diverse sonic experience. While this was not a

significant consideration during the time of making, it persists to be a

significant feature of the work, especially as connections between practice,

discipline and identity have begun to emerge.

Thus, in using this image-based approach, the outcome was not only a musical translation but also a visual and physical object. Hand-writing the first draft of the score allowed me to physically engage with the process, the text, and the score. The process also precipitated a negotiation of the way these methods could result in an outcome that made musical sense. The term musical sense can be understood to mean many things regarding how we read and interpret music, but here, I use the term to refer to idiomatic writing and playability. That is to say, musical sense here means the fluency of the music that allows the musician to understand and interpret it, both in terms of single lines (individual instrumental parts) and the score as a whole. This process had to engage with the practical consideration that as a score, it would be encountered and played by musicians in an orchestra.

Making sense was a key consideration throughout the process. As Venuti points out in The Translator’s Invisibility, what is seen as a successful translation is often contextualised within the values of the receiving culture or language.19 Taking this into account, as well as the influences of Australia’s majority English-speaking culture, fluency is valued over other methods of translation and thus determines the success of the translation. While the generative processes discussed above produced a seemingly rough translation (perhaps not in relation to the process, but rather to the initial translated result), it was important that the translation should make sense to the receiver (in this case, the musician). Music, specifically western classical music, and even more specifically, orchestral western classical music is substantially beholden to strict and deeply embedded rules and traditions. This necessitated changes that elasticised the limitations of the processes discussed, and in turn, enabled a greater sense of musical fluency. After all, considered within his framework of translation, Venuti has succinctly put, ‘translation is not an untroubled communication of a foreign text, but an interpretation that is always limited by its address to specific audiences and by the cultural or institutional situations where the translated text is intended to circulate and function.’20 Therefore, for the success of this translation, or for it to be viewed and understood as orchestral music (or deemed “well-written” according to musicians in regards to both technique and musical style), the score needed to be adjusted to be more idiomatically written for musicians and for the orchestra.

Discussion

There are many lines of enquiry that have emerged through the development and outcomes of this project, including parallel relations between the expectations that exist within the Asian-Australian experience and the assumed role of the composer in classical and art music traditions. The process of translation between textual language and music composition resulted in multiple layers of language in both visual and auditory form. On reflection, I find myself struggling to speak to the work, as I feel as though I cannot easily locate it or clearly identify the language of the form it takes. Each time I think I’ve located the crux of the work, it becomes slippery and the difficulty in grasping the effects of the translation constantly produces new ideas and alternate perspectives.

Developed as a result of mutual insufficiency between music (material) and language (concept), this project exists as a process, an act, an object, a text, an image, a score and as sound or a sounding musical work. Each of these framings potentially perform a different function, but can any one of them account for the aims and outcome of the project as a whole? Within the scope of this project, focus was brought to the process and its development, but where does that leave the creative outcome or the translation? The form or definition of the work is seemingly ambiguous as it focused on a process or action that happened to result in an outcome.

Keeping in mind the initial premise of translating Chinese to music, it is important to consider the work through a musical framework. A score was made, a piece was written, and there was a resultant sound, but how it sounded stylistically was not necessarily important. Does this devalue or invalidate it as a piece of music, or does the piece perform some other function? The work can also be considered through a more ocular-centric and material lens. Taking into account the materiality, visuality and physicality of the text and music with which the process dealt, the work becomes both text and object as the score is a physical transfer of the text, and simultaneously is the text. When considering the outcome as anything but music, how can we test the success of the translation?

As I reflect on the work, more questions emerge as the work inhabits a state of ambiguity and oscillation between functions, meanings, and forms. Will locating or defining the form of the work suddenly invalidate its existence as anything else? Or what are the potentials of it occupying these multifaceted and contested spaces simultaneously, or the space in-between them?

These questions have engaged a thread of discussion surrounding the space in-between and the creative potentials that exist with the hybridity that it breeds. In her book On Not Speaking Chinese, Ang speaks about positions of in-between-ness as a space of multi-perspectival productivity and hybridity,21 stating that ‘hybridity is a concept which confronts and problematises all these boundaries, although it does not erase them. As a concept, hybridity belongs to the space of the frontier, the border, the contact zone. As such, hybridity always implies a blurring or at least a problematising of boundaries, and as a result, an unsettling of identities.’22 While she refers to cultural identities within the context of her writing, particularly in relation to Chineseness, biculturality and diasporic experience, these notions of hybridity can be just as useful in considering the way in which this work can sit within the interstices of defined disciplines and fixed mediums, and resultingly, perhaps mirror the in-between-ness of the Asian-Australian experience in some ways.

Furthermore, we can consider the work through the lens of Venuti’s The Translator’s Invisibility, in which he draws upon Friedrich Schleiermacher’s notions of translation methods and to speculate on two key approaches—‘bringing the author back home’ or ‘sending the reader abroad.’23 He posits that translation can go one of two ways, the first, ‘bringing the author back home’ implies that the translation prioritises the reader and contextualises the text within the reader’s cultural setting. The second, ‘sending the reader abroad’ points towards a translation that prioritises the culture and context of the author. With this framework in mind, we might consider where this project can be positioned as a translation exercise, and I would propose that rather than sitting at either of the dichotomous ends, this translation instead occupies a space in-between the two methods proposed by both Schleiermacher and Venuti. The processes of making and translating, revolved around constant negotiations, reconfigurations and reinterpretations of the two languages, and it is through this positioning that the translation potentially offers us a mirroring of Ang’s notions of Chineseness in the way that it is never fixed or determined.24

Furthermore, without considering the work’s intended or potential audiences, or (in terms of translation) readers, I am unable to grasp the success of the work as a translation if we consider success through Venuti’s framework of fluency. If we think about the outcome as a musical work, we could potentially consider the orchestra musicians as the readers of the translation. However, depending on if the work sounds (that is, if it is played and heard by a listening audience), are the listeners the readers of the translation instead, or in addition to, the musicians? These considerations occur when the work is viewed through the lens of the discipline of music. What, or who then are the audiences, and how is the work consumed if considered through the lens of the other forms discussed above, such as text, image, or object? These questions are rich and open the research to more fertile lines of enquiry that require further critical exploration.

![]() [Figure 5] Kezia Yap, image example of an excerpt handwritten score

within the shape of the overlaid text

[Figure 5] Kezia Yap, image example of an excerpt handwritten score

within the shape of the overlaid text

My final line of thought questions how and to what extent this project has facilitated establishing an understanding of my own identity as an Asian-Australian artist, and how it has given meaning or some sort of authenticity to these labels. Earlier, I briefly discussed Hall’s notions surrounding identity as a device from which to speak as a motivating concept for this translation project. However in The Translator’s Invisibility, Venuti discusses a particular framework that implies, assuming that the success of a translation is measured in fluency above other methods, that a “good” or successful translation renders the translator invisible, stating that ‘the more fluent the translation, the more invisible the translator.’25 Then, if considered through this framework, a successful translation may compromise the establishment of identity by rendering it invisible, as my position in this project is also that of the translator. Therefore, it leaves the work, the translation, and the establishment of identity, in an interesting place of ambiguity where success may not be simultaneously possible through each of the discussed conceptual frameworks.

This project has both illuminated and set into motion a series of enquiries around translation, Chineseness, bicultural identity, musical reading and interpretation that revel in the potentials of the in-between spaces produced through culture and creative practice. This work has broadened the scope of research and expanded my artistic practice, whilst providing a framework to delve deeper into the initial questions that motivated it. The journey of this creative translation has challenged the disciplinary and formal boundaries within my own work, and consequently engaged with new perspectives of my positioning as both an Asian-Australian and an artist. As this project has deepened certain lines of enquiry, I will continue to explore and attempt to navigate the potentials that emerge from the fertile and productive in-between spaces that exist within both the Asian-Australian and interdisciplinary artistic contexts.

Thus, in using this image-based approach, the outcome was not only a musical translation but also a visual and physical object. Hand-writing the first draft of the score allowed me to physically engage with the process, the text, and the score. The process also precipitated a negotiation of the way these methods could result in an outcome that made musical sense. The term musical sense can be understood to mean many things regarding how we read and interpret music, but here, I use the term to refer to idiomatic writing and playability. That is to say, musical sense here means the fluency of the music that allows the musician to understand and interpret it, both in terms of single lines (individual instrumental parts) and the score as a whole. This process had to engage with the practical consideration that as a score, it would be encountered and played by musicians in an orchestra.

Making sense was a key consideration throughout the process. As Venuti points out in The Translator’s Invisibility, what is seen as a successful translation is often contextualised within the values of the receiving culture or language.19 Taking this into account, as well as the influences of Australia’s majority English-speaking culture, fluency is valued over other methods of translation and thus determines the success of the translation. While the generative processes discussed above produced a seemingly rough translation (perhaps not in relation to the process, but rather to the initial translated result), it was important that the translation should make sense to the receiver (in this case, the musician). Music, specifically western classical music, and even more specifically, orchestral western classical music is substantially beholden to strict and deeply embedded rules and traditions. This necessitated changes that elasticised the limitations of the processes discussed, and in turn, enabled a greater sense of musical fluency. After all, considered within his framework of translation, Venuti has succinctly put, ‘translation is not an untroubled communication of a foreign text, but an interpretation that is always limited by its address to specific audiences and by the cultural or institutional situations where the translated text is intended to circulate and function.’20 Therefore, for the success of this translation, or for it to be viewed and understood as orchestral music (or deemed “well-written” according to musicians in regards to both technique and musical style), the score needed to be adjusted to be more idiomatically written for musicians and for the orchestra.

Discussion

There are many lines of enquiry that have emerged through the development and outcomes of this project, including parallel relations between the expectations that exist within the Asian-Australian experience and the assumed role of the composer in classical and art music traditions. The process of translation between textual language and music composition resulted in multiple layers of language in both visual and auditory form. On reflection, I find myself struggling to speak to the work, as I feel as though I cannot easily locate it or clearly identify the language of the form it takes. Each time I think I’ve located the crux of the work, it becomes slippery and the difficulty in grasping the effects of the translation constantly produces new ideas and alternate perspectives.

Developed as a result of mutual insufficiency between music (material) and language (concept), this project exists as a process, an act, an object, a text, an image, a score and as sound or a sounding musical work. Each of these framings potentially perform a different function, but can any one of them account for the aims and outcome of the project as a whole? Within the scope of this project, focus was brought to the process and its development, but where does that leave the creative outcome or the translation? The form or definition of the work is seemingly ambiguous as it focused on a process or action that happened to result in an outcome.

Keeping in mind the initial premise of translating Chinese to music, it is important to consider the work through a musical framework. A score was made, a piece was written, and there was a resultant sound, but how it sounded stylistically was not necessarily important. Does this devalue or invalidate it as a piece of music, or does the piece perform some other function? The work can also be considered through a more ocular-centric and material lens. Taking into account the materiality, visuality and physicality of the text and music with which the process dealt, the work becomes both text and object as the score is a physical transfer of the text, and simultaneously is the text. When considering the outcome as anything but music, how can we test the success of the translation?

As I reflect on the work, more questions emerge as the work inhabits a state of ambiguity and oscillation between functions, meanings, and forms. Will locating or defining the form of the work suddenly invalidate its existence as anything else? Or what are the potentials of it occupying these multifaceted and contested spaces simultaneously, or the space in-between them?

These questions have engaged a thread of discussion surrounding the space in-between and the creative potentials that exist with the hybridity that it breeds. In her book On Not Speaking Chinese, Ang speaks about positions of in-between-ness as a space of multi-perspectival productivity and hybridity,21 stating that ‘hybridity is a concept which confronts and problematises all these boundaries, although it does not erase them. As a concept, hybridity belongs to the space of the frontier, the border, the contact zone. As such, hybridity always implies a blurring or at least a problematising of boundaries, and as a result, an unsettling of identities.’22 While she refers to cultural identities within the context of her writing, particularly in relation to Chineseness, biculturality and diasporic experience, these notions of hybridity can be just as useful in considering the way in which this work can sit within the interstices of defined disciplines and fixed mediums, and resultingly, perhaps mirror the in-between-ness of the Asian-Australian experience in some ways.

Furthermore, we can consider the work through the lens of Venuti’s The Translator’s Invisibility, in which he draws upon Friedrich Schleiermacher’s notions of translation methods and to speculate on two key approaches—‘bringing the author back home’ or ‘sending the reader abroad.’23 He posits that translation can go one of two ways, the first, ‘bringing the author back home’ implies that the translation prioritises the reader and contextualises the text within the reader’s cultural setting. The second, ‘sending the reader abroad’ points towards a translation that prioritises the culture and context of the author. With this framework in mind, we might consider where this project can be positioned as a translation exercise, and I would propose that rather than sitting at either of the dichotomous ends, this translation instead occupies a space in-between the two methods proposed by both Schleiermacher and Venuti. The processes of making and translating, revolved around constant negotiations, reconfigurations and reinterpretations of the two languages, and it is through this positioning that the translation potentially offers us a mirroring of Ang’s notions of Chineseness in the way that it is never fixed or determined.24

Furthermore, without considering the work’s intended or potential audiences, or (in terms of translation) readers, I am unable to grasp the success of the work as a translation if we consider success through Venuti’s framework of fluency. If we think about the outcome as a musical work, we could potentially consider the orchestra musicians as the readers of the translation. However, depending on if the work sounds (that is, if it is played and heard by a listening audience), are the listeners the readers of the translation instead, or in addition to, the musicians? These considerations occur when the work is viewed through the lens of the discipline of music. What, or who then are the audiences, and how is the work consumed if considered through the lens of the other forms discussed above, such as text, image, or object? These questions are rich and open the research to more fertile lines of enquiry that require further critical exploration.

[Figure 5] Kezia Yap, image example of an excerpt handwritten score

within the shape of the overlaid text

[Figure 5] Kezia Yap, image example of an excerpt handwritten score

within the shape of the overlaid textMy final line of thought questions how and to what extent this project has facilitated establishing an understanding of my own identity as an Asian-Australian artist, and how it has given meaning or some sort of authenticity to these labels. Earlier, I briefly discussed Hall’s notions surrounding identity as a device from which to speak as a motivating concept for this translation project. However in The Translator’s Invisibility, Venuti discusses a particular framework that implies, assuming that the success of a translation is measured in fluency above other methods, that a “good” or successful translation renders the translator invisible, stating that ‘the more fluent the translation, the more invisible the translator.’25 Then, if considered through this framework, a successful translation may compromise the establishment of identity by rendering it invisible, as my position in this project is also that of the translator. Therefore, it leaves the work, the translation, and the establishment of identity, in an interesting place of ambiguity where success may not be simultaneously possible through each of the discussed conceptual frameworks.

This project has both illuminated and set into motion a series of enquiries around translation, Chineseness, bicultural identity, musical reading and interpretation that revel in the potentials of the in-between spaces produced through culture and creative practice. This work has broadened the scope of research and expanded my artistic practice, whilst providing a framework to delve deeper into the initial questions that motivated it. The journey of this creative translation has challenged the disciplinary and formal boundaries within my own work, and consequently engaged with new perspectives of my positioning as both an Asian-Australian and an artist. As this project has deepened certain lines of enquiry, I will continue to explore and attempt to navigate the potentials that emerge from the fertile and productive in-between spaces that exist within both the Asian-Australian and interdisciplinary artistic contexts.

[Figure 6] Kezia Yap, image of the final score for workshop with

the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra

Notes:

1. Ien Ang, “On Not Speaking Chinese: Diasporic Identifications and Postmodern Ethnicity,” in On Not Speaking Chinese: Living between Asia and the West (London, UNITED KINGDOM: Routledge, 2001), 30.

2. Ibid. 30.

3. Ibid. 25.

4. Ibid. 35.

5. Ibid. 24.

6. Toru Takemitsu, “Conversation on Seeing,” in Confronting Silence: Selected Writings, trans. Yoshiko Kakudo and Glenn Glasow (Berkeley, California, United States of America: Fallen Leaf Press, 1995), 37.

7. Salman Rushdie, Imaginary Homelands: essays and criticisms, 1981-1991, Granta Books, 1991, quoted in Ien Ang, “On Not Speaking Chinese: Diasporic Identifications and Postmodern Ethnicity,” in On Not Speaking Chinese: Living between Asia and the West (London, UNITED KINGDOM: Routledge, 2001), 35.

8. Ien Ang, “On Not Speaking Chinese: Diasporic Identifications and Postmodern Ethnicity,” in On Not Speaking Chinese: Living between Asia and the West (London, UNITED KINGDOM: Routledge, 2001), 35.

9. Ibid. 4.

10. Mia Salsjö, Modes of Translation, present 2016, graphite, coloured pencil, ink, pen on felt, industrial fasteners. notebooks, performance, music, video installation, 2016-present.

11. Lawrence Venuti, “Chapter 1: Invisibility,” in The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation (New York, United States of America: Routledge, 2018), 13.

12. These sentences remain untranslated into English to bring more focus to the act of translation between Chinese and music.

13. Spoken Mandarin consists of four tones that will change the meaning of the word when applied to characters or syllables with the same sound.

14. Ferragina’s work presented at the 20th Generative Art Conference attempts to create a system that generates music (generating pitched or melodic content) using strokes and gestures in Chinese calligraphy. His process involved the collection of data surrounding measurement of strokes, direction, fundamental strokes, and time between strokes. These were then mapped to specific pitches and durations to compose a melody.

15. Silvio Ferragina, “The Music of Chinese Calligraphy,” in Proceedings of the XX Generative Art Conference, ed. Celestino Soddu and Enrica Colabella (20th Generative Art Conference, Ravenna, Italy, 2017), 395–412.

16. Here, it may be interesting to note that when translating this character from Chinese (jiān, literally translating to space in between, among, room), it produces a similar or related definition. It may also be important to note here that both Japanese and Korean languages utilise characters derived from the Chinese language (Kanji in Japanese and Hanja in Korean) in addition to their own phonetic characters, and so we can sometimes see overlap in the meanings of similar characters across these languages.

17. Toru Takemitsu, “A Single Sound,” in Confronting Silence: Selected Writings, trans. Yoshiko Kakudo and Glenn Glasow (Berkeley, California, United States of America: Fallen Leaf Press, 1995), 51.

18. Ibid. 51.

19. Lawrence Venuti, “Chapter 1: Invisibility,” in The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation (New York, United States of America: Routledge, 2018), 14.

20. Lawrence Venuti, “Chapter 1: Invisibility,” in The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation (New York, United States of America: Routledge, 2018), 14.

21. Ien Ang, “On Not Speaking Chinese: Diasporic Identifications and Postmodern Ethnicity,” in On Not Speaking Chinese: Living between Asia and the West (London, UNITED KINGDOM: Routledge, 2001), 35.

22. Ien Ang, “Introduction: Between Asia and the West (In Complicated Entanglement),” in On Not Speaking Chinese: Living between Asia and the West (London, UNITED KINGDOM: Routledge, 2001), 16.

23. Lawrence Venuti, “Chapter 1: Invisibility,” in The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation (New York, United States of America: Routledge, 2018), 15.

24. Ien Ang, “On Not Speaking Chinese: Diasporic Identifications and Postmodern Ethnicity,” in On Not Speaking Chinese: Living between Asia and the West (London, UNITED KINGDOM: Routledge, 2001), 30.

25. Lawrence Venuti, “Chapter 1: Invisibility,” in The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation (New York, United States of America: Routledge, 2018), 1.

1. Ien Ang, “On Not Speaking Chinese: Diasporic Identifications and Postmodern Ethnicity,” in On Not Speaking Chinese: Living between Asia and the West (London, UNITED KINGDOM: Routledge, 2001), 30.

2. Ibid. 30.

3. Ibid. 25.

4. Ibid. 35.

5. Ibid. 24.

6. Toru Takemitsu, “Conversation on Seeing,” in Confronting Silence: Selected Writings, trans. Yoshiko Kakudo and Glenn Glasow (Berkeley, California, United States of America: Fallen Leaf Press, 1995), 37.

7. Salman Rushdie, Imaginary Homelands: essays and criticisms, 1981-1991, Granta Books, 1991, quoted in Ien Ang, “On Not Speaking Chinese: Diasporic Identifications and Postmodern Ethnicity,” in On Not Speaking Chinese: Living between Asia and the West (London, UNITED KINGDOM: Routledge, 2001), 35.

8. Ien Ang, “On Not Speaking Chinese: Diasporic Identifications and Postmodern Ethnicity,” in On Not Speaking Chinese: Living between Asia and the West (London, UNITED KINGDOM: Routledge, 2001), 35.

9. Ibid. 4.

10. Mia Salsjö, Modes of Translation, present 2016, graphite, coloured pencil, ink, pen on felt, industrial fasteners. notebooks, performance, music, video installation, 2016-present.

11. Lawrence Venuti, “Chapter 1: Invisibility,” in The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation (New York, United States of America: Routledge, 2018), 13.

12. These sentences remain untranslated into English to bring more focus to the act of translation between Chinese and music.

13. Spoken Mandarin consists of four tones that will change the meaning of the word when applied to characters or syllables with the same sound.

14. Ferragina’s work presented at the 20th Generative Art Conference attempts to create a system that generates music (generating pitched or melodic content) using strokes and gestures in Chinese calligraphy. His process involved the collection of data surrounding measurement of strokes, direction, fundamental strokes, and time between strokes. These were then mapped to specific pitches and durations to compose a melody.

15. Silvio Ferragina, “The Music of Chinese Calligraphy,” in Proceedings of the XX Generative Art Conference, ed. Celestino Soddu and Enrica Colabella (20th Generative Art Conference, Ravenna, Italy, 2017), 395–412.

16. Here, it may be interesting to note that when translating this character from Chinese (jiān, literally translating to space in between, among, room), it produces a similar or related definition. It may also be important to note here that both Japanese and Korean languages utilise characters derived from the Chinese language (Kanji in Japanese and Hanja in Korean) in addition to their own phonetic characters, and so we can sometimes see overlap in the meanings of similar characters across these languages.

17. Toru Takemitsu, “A Single Sound,” in Confronting Silence: Selected Writings, trans. Yoshiko Kakudo and Glenn Glasow (Berkeley, California, United States of America: Fallen Leaf Press, 1995), 51.

18. Ibid. 51.

19. Lawrence Venuti, “Chapter 1: Invisibility,” in The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation (New York, United States of America: Routledge, 2018), 14.

20. Lawrence Venuti, “Chapter 1: Invisibility,” in The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation (New York, United States of America: Routledge, 2018), 14.

21. Ien Ang, “On Not Speaking Chinese: Diasporic Identifications and Postmodern Ethnicity,” in On Not Speaking Chinese: Living between Asia and the West (London, UNITED KINGDOM: Routledge, 2001), 35.

22. Ien Ang, “Introduction: Between Asia and the West (In Complicated Entanglement),” in On Not Speaking Chinese: Living between Asia and the West (London, UNITED KINGDOM: Routledge, 2001), 16.

23. Lawrence Venuti, “Chapter 1: Invisibility,” in The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation (New York, United States of America: Routledge, 2018), 15.

24. Ien Ang, “On Not Speaking Chinese: Diasporic Identifications and Postmodern Ethnicity,” in On Not Speaking Chinese: Living between Asia and the West (London, UNITED KINGDOM: Routledge, 2001), 30.

25. Lawrence Venuti, “Chapter 1: Invisibility,” in The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation (New York, United States of America: Routledge, 2018), 1.

About the contributor:

Kezia Yap is a Naarm

(Melbourne)-based artist and composer. She is a graduate of the Sydney

Conservatorium of Music and a current MFA candidate at the Victorian College of

the Arts. Working across sound, music, installation and performance, her

practice and research interrogates intersections of Asian-Australian cultural

identity and interdisciplinary practice through explorations of ambiguous and

in-between spaces.

Currents is a collaboration between the Centre of Visual Art (CoVA) at the University of Melbourne and the School of Design, University of Western Australia, and is funded through the Schenberg International Arts Collaboration Program. The Advisory Board and Editorial Committee are comprised of staff and graduate students from across the University of Melbourne and the University of Western Australia.

Currents acknowledges the traditional owners and ongoing custodians of the land on which this journal is produced—the Boonwurung and Wurundjeri people of the Eastern Kulin Nation and Whadjuk people. We pay our respects to land, ancestors and Elders, and know that education involves working with their guidance to improve the lives of all.

ISSN 2652-8207

![]()

![]()

Currents acknowledges the traditional owners and ongoing custodians of the land on which this journal is produced—the Boonwurung and Wurundjeri people of the Eastern Kulin Nation and Whadjuk people. We pay our respects to land, ancestors and Elders, and know that education involves working with their guidance to improve the lives of all.

ISSN 2652-8207