Currents ‘Issue Two’ begins with Donna Lyon’s reflexive, epistolary reflection on the production of a practice-led digital archive research project, for pedagogical, research and engagement purposes. Rina Angela Corpus narrates the complex linguistic, somatic and artistic influences of her dance piece Still One. Artist Jen Valender conducts an interview with the artist Gabriella Hirst, discussing her recent commission Darling Darling, which captures the hypocrisy, absurdity and discrepencies between ecological care and its representation. Kelly Fliedner reviews ‘Olga Cironis: This Space Between Us’ and its important contribution to local art historical knowledge. Driven by another year of border closures, lockdowns and academic disconnect Currents editors Jeremy Eaton and Kelly Fliedner have interspersed ‘Issue Two’ with a series of conversations with Ashley Perry, Therese Keogh, Elham Eshraghian-Haakansson and Sacha Barker.

Contents

- Producing the Self: an epistolary reflection of a PhD research journey — Dr Donna Lyon

- Galaw-nilay: Articulating Interiority in Meditative Movement —Rina Angela Corpus

- The link, the limits between: performance and capture in the moving image — Jen Valender in Conversation with Gabriella Hirst

- A review of ‘Olga Cironis: This Space Between Us’ — Kelly Fliedner

- Currents Conversations —Elham Eshraghian-Haakansson

Producing the Self: an epistolary reflection of a PhD

research journey

Dr Donna Lyon

To cite this contribution:

Lyon, Donna. ‘Producing the Self: an epistolary reflection of a PhD

research journey’. Currents Journal Issue Two (2021), https://currentsjournal.net/Dear Researcher

Download this article ︎︎︎PDF

Course of study:

Doctor of Philosophy, Faculty of Fine Arts and Music (Film), University of Melbourne

Keywords:

digital archive, auto/biography, reflexivity, producing, epistolary, epistemology, ontology.

Abstract:In this letter to research graduates, author Donna Lyon embarks on a reflexive account of her PhD research journey. She explores the methodological challenges of producing a practice-led digital archive research project, for pedagogical, research and engagement purposes. Alongside this, is a reflective discussion on the personal and professional discoveries that she made along the way. The author shifts from the pragmatism of being an effective industry producer to one who introduces broader reflections of her processes and their implications on the practice, enhancing the action-based nature of the exploration. This precipitated a broader reflective practice, combining the authors personal experiences of publicly claiming her experiences as a survivor of childhood sexual abuse and how it informed her working methods and relationship to the research and films in the archive. As the films in the archive were transformed from old media into new media, so too was the researcher’s personal and professional identity as she began to express and re-claim self.

digital archive, auto/biography, reflexivity, producing, epistolary, epistemology, ontology.

Abstract:In this letter to research graduates, author Donna Lyon embarks on a reflexive account of her PhD research journey. She explores the methodological challenges of producing a practice-led digital archive research project, for pedagogical, research and engagement purposes. Alongside this, is a reflective discussion on the personal and professional discoveries that she made along the way. The author shifts from the pragmatism of being an effective industry producer to one who introduces broader reflections of her processes and their implications on the practice, enhancing the action-based nature of the exploration. This precipitated a broader reflective practice, combining the authors personal experiences of publicly claiming her experiences as a survivor of childhood sexual abuse and how it informed her working methods and relationship to the research and films in the archive. As the films in the archive were transformed from old media into new media, so too was the researcher’s personal and professional identity as she began to express and re-claim self.

Dear Graduate Researcher,

I did it! I am a Dr. The first in my family history! I write to tell you the news but more than that, to share some of my scholarly journey. But why write a letter you ask? Well, I must declare upfront that I do have an attraction to the epistolary form as a mode of self-expression. It was sparked by mother, a submissive type, who I watched as a child write cursive letters to her acquaintances on Sunday evenings. As I grew and we drifted, she would write to me over the years. It was her way of connecting, although I must say that her letters were never deep. They were hard to read and focused on the mundane, yet I sensed her desire to express herself. Her letters frustrated me, but there was something about the form that I was drawn to. Perhaps I longed to be able to communicate with her and for her to write the truth.

Did you know that the narrative form of letter writing became popularised by women during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries? Letters were seen as an acceptable form of communication back then, in which women could express themselves easily, offering little to no challenge to the chronicles of man.1 Do not worry, my letter to you will be more than an attempt at self-expression. At times I will include academic interludes, and most certainly you will get some potted personal history. I hope to at least achieve some of the characteristics of letter writing that Hallett describes as heartfelt, truthful, idealistic, moody, anxiety-ridden, manipulative, temporal, yet ‘of the moment.’2 By choosing this form my dear researcher, I am attempting to reflexively recount an auto/biographic experience of my PhD research journey. Yet, by making the choice to go with this genre, I am acutely aware of the ethical and epistemological implications of my decision:

What I can only admit to as a slow, somewhat uneasy research process, ‘I’4 not only produced a multi-platform digital archive project, ‘I’ produced a multi-faceted version of self. I write this letter to you then as an experiential and contextual analysis of how I constructed and became a knowledge-producer of my research enquiry (into that of my practice and existential self). My hope is that as practice-researchers, you might be inspired to consider what is your construction of self and how it has influenced your research. For the non-practice researchers reading this, may this letter serve to advance your knowledge about how one’s practice can influence and support new knowledge.

But of course, as I write this, the anxiety that Hallett warned as evident to this form has begun to reveal itself; ‘(Will I achieve the right tone?’5 The obsession has begun. What happens when I send it? Will my words be dismissed as self-reflexive drivel? Will it be peer-reviewed? Will you reject me? Will I remain misunderstood? My attempt to connect with you may indeed fall flat. For how you receive my words is outside of my control, yet here I go…

When I entered the world of research, I had little depth and understanding of the actual term ‘research’. You see, I was more of a practitioner type back then and my modus operandi was to find out the information, decide on a course of action and move on. I was pragmatic, logical, and decisive (it was, and remains a rather efficient way to live my life).I struggled to make sense of why one would spend so much time investigating things without a clear result. Worse, was the idea that you could spend so much time researching something that may be disproved or eventuate to nothing. How mortifying!

Allow me to retrace my steps for you… I began working at the University of Melbourne, Victorian College of the Arts (VCA) Film and Television department in 2013 in a professional role. Here, I oversaw the administration and compliance of the student short films produced in the film department. I was known by staff as a ‘fixer’, a problem solver (dare I say, a woman of action?). I took on the responsibility for distribution deals related to the student films attracting the last vestiges of broadcast support. By the end of that year, Apple had stopped making its MacBook pro computers with DVD drives, and Blockbuster announced it was closing its DVD stores. Technology was killing the video store, and the need for VCA Film and Television to embrace online distribution and the digital access of its films, was fast becoming a pressing issue.

Students wanted to screen their films online and share their work easily amongst peers, beyond the traditional pathway of the film festival circuit. I became inspired by a staff member, who casually remarked one day that our department could solve these problems if it set up its very own YouTube channel. I decided to take on the project and swiftly enrolled into my masters, where some of you who are reading this letter will be situated. Within a year I converted to a doctoral degree, recalling the MFA supervisor stating that I was creating a lifetime job for myself at the institution. Little did I know that his words would begin to ring true, as seven years later the project continues to evolve.

Initially I chose to investigate the practicalities and challenges of designing and strategising a YouTube style internet channel for the VCA Film School—aptly titled VCATube. VCA held in its archive room, over 1,750 student films dating back to 1966, acknowledging its early lineage from Swinburne Technical College (now Swinburne University), marking it as Australia’s inaugural film school.6 I hope you don’t mind, but I feel I need to give you some further background knowledge to the institutional home of this project for this story to make more sense. In 1992, Swinburne amalgamated into VCA, before merging into the University of Melbourne and settling into the Faculty of Fine Arts and Music, where it currently resides. At the time of the consolidation, the audiovisual holdings were transferred to VCA, along with the ethos of the film school; practice-based filmmaking (learning by doing). Founder, Brian Robinson, had been inspired by the practice-based framework he observed whilst visiting the University of California in the 1960s.7 In the 1960s and 1970s, experimental modes of practice were common to arts making and became a popular form of filmmaking by students at the film school.8

In 2006, I had completed my postgraduate study in producing at VCA, and gained a deeper understanding of the blood, sweat and tears required to make student short films. Coupled with my industry experience, taking on a large-scale multi-platform project did not phase me, yet the academic research felt like an uncomfortable fit. You see, I was a producer and I produced content with an audience in mind. In case you do not know about the role of the film producer, Eve Honthaner, describes the job remit quite well:

To achieve a film, my goal has always been to bring together skilled players with their various expertise to realise the writer/director’s vision. So, when I heard of practice-led research, it made sense to me as a framework; the practice of filmmaking driving the research enquiry process. Yet I must confess, I did not understand why I needed to provide an argument for how I did things. Why should I lay claim to how I arrived at knowledge, particularly if it worked? Why over analyse and complicate things?

Over time, I discovered that the process of ‘doing’ was a legitimate form of research, so it was not surprising then that after making some headway in the ‘doing’ of the project, that I happened upon ‘action research’. You might be aware that there are many modes of action research (I will simplify from here as AR), and that it is a term coined by the social scientist Kurt Lewin in the 1950s. AR is used most often in the field of educational research, but can be very effective in participatory and arts based research (if you want to know more, I suggest hunting down Dick 1993; Zuber-Skerrit 1996; Whitehead and McNiff 2006; Greenwood and Levin 2011; Kemmis, McTaggart and Nixon 2014). Simply my friend, if it is okay to call you such, AR is a cyclical process that follows four steps; plan, act, observe, reflect.10 However, this redaction is defended by researchers such as McTaggart, who see AR as ‘…a series of commitments to observe and problematise through practice of a series of principles for conducting social enquiry.’11 Zuber-Skerritt asserts the objective of AR is ‘to bring about practical improvement, innovation, change or development of social practice, and the practitioners’ better understanding of their practices.’12

As I had come to the research from a practitioner’s perspective, I felt responsive to the idea of bringing about organisational change to better processes and practice. When I arrived at VCA, I had discovered a systematic problem—a situation that demanded responsiveness. Simply, no one could easily access the past films made by film students, unless they had a library card and DVD player. DVD was dying and the threat of format obsolescence ever pressing. Discovering this problem soon led to more than setting up a YouTube channel for the film school. Rather, it became an exploration of the challenges and stages of developing and producing a wide scale digitisation, preservation, and access digital archive research project for teaching, learning, research and engagement.

Allow me to digress to offer up a definition of the archive. The word archive derives from the Greek word ‘arkheion’ meaning a house; a domicile.13 Steedman says that inside its domicile ‘The Archive is made from selected and consciously chosen documentation from the past and also from the mad fragmentations that no one intended to preserve and that just ended up there.’14 Don’t you love this idea of mad fragmentations? It provokes in me the need to make some semblance of order. In the VCA Film and Television archive there were 16mm films, magnetic media (Digital Betacam, Betacam SP, HDCAM and Umatic magnetic tapes, a large collection of stills, catalogues and production paperwork associated with the making of the films). I am not sure how much you know about digitisation and the like, but to digitise a film means more than creating a digital version. It means producing multiple digital versions and formats that then need to be further archived in a digital repository with their associated metadata (data about data), to ensure their long-term value and accessibility.

The technical intricacies of an archive project are not dissimilar from the complexities of a film project. For filmmaking is made up of many parts and is inherently collaborative and interdisciplinary. Archives also need to connect with various disciplines, such as records management, library and computer science, through to new media and digital and cultural heritage preservation. As a producer on independent projects, I might wear several hats, and so too in the digital archive project, I found myself becoming a multiple operator. I played the role of pseudo archivist, record keeper and information management expert. Yet metadata muddled me, and the granular thinking required in these disciplines turned my stomach. I know, I know! I hear you thinking… the process of organisational change is slow and difficult! You are right. Research proves that it is conditional upon achieving several factors, which Zuber-Skerrit defines as:

I’ll be honest, I found it difficult to achieve any of these things within VCA Film and Television and the wider university. Lack of resourcing, time and conflicting schedules impeded on my ideal of setting up a collaborative and participatory based digital archive project.

Outside of the practical project, I felt overwhelmed and confused by the theory surrounding the practice. I was a big picture thinker (admittedly prone to internal flights of fancy). I struggled to give expression to complex thoughts and ideas. You might describe this my friend, as a form of imposter syndrome, but really, I was battling daily with negative self-talk and low self-esteem.

As I moved through the many action steps required to research and plan the project, new revelations dawned on me. AR, as a process of social enquiry and an attempt to gain a better understanding of one’s practice,16 meant that I was naturally inquiring into the way I was going about things. I discovered that I had been taking action to keep me from myself! Sure, I liked to plan, observe and share, but I struggled to reflect. The idea of being in my body and head long enough to notice what was going on, seemed foreign, incomprehensible and frankly, rather unpleasant (l will come back to this later, I promise…).

Firstly though, I want to give you a bit more context of this research to show you the breadth of the project and to assure you that the research was situated within a larger discourse of film preservation in Australia and internationally (the challenges I faced were not just about my inner world, they were also about audiovisual preservation). Lack of time, resourcing, equipment, and funding were the key problems cited in ensuring the large numbers of film and analogue material could be sufficiently digitised.17 There were issues of software and hardware progression, commerciality, cultural heritage, economic sustainability and risk management, among others. Add to this, the enormity of digital data and complex databases, plus the inability of local storage devices to accommodate these things,18 the digital archive project was formidable.

Don’t worry my friend, I achieved small wins along the way. As I moved pragmatically through the research journey, I discovered that I had been operating professionally as a screen producer with a tacit knowledge of my practice, what Donald Schon would describe as ‘knowing-in-practice.’19 My implicit understanding of my practice was in many ways a form of research, not yet made explicit. I reflected in action—through the act of asking questions, engaging with stakeholders, meetings, emails, notes. These simple acts informed each moment and became how I constructed knowledge and made meaning.

Let us pause momentarily here my dear researcher, as this is an important point. You see, I was beginning to realise that my ability to construct knowledge was indeed legitimate (you might already know this as a constructivist approach!).20 The process of research forced me to stop and reflect on my practice—how I operated and discovered knowledge for its translation.

As I began to tie together my methodology, combining action and filmmaking research, I saw that my process fitted in with Denzin’s method of interpretive interactionism. ‘The biographical, interpretive method rests on the collection, analysis, and performance of stories, accounts, and narratives that speak to turning-point moments in people's lives.’21 My inward reflexive process started to become unapologetically subjective as you are about to read.

As I began to articulate my research journey and explain meaning, my epistemic discoveries opened into a broader ontological discovery. I began to see that from an early age, I had been (re)constructing a sense of self, motivated by a desperate need to (re)build a fragmented identity borne out of being a survivor of extreme sexual and mental abuse. In the early years of my research, the process of ‘doing’ was so natural and easy to me. I produced task lists, milestones, project plans and funding applications. I took the project beyond a theoretical investigation and practically produced it. I led the digitisation, preservation and curation of over 1,750 student films, ensuring their accessibility on a university supported digital platform.

Yet, it wasn’t until years into the research, after the doing of the project, that I began to observe that I had not valued the practice of screen producing enough to consider it as a legitimate and justifiable mode of research. So, I drew on many forms of action research, all of which helped drive my line of inquiry, but the truth was, I kept falling back into my skills of producing, and the processes by which I would make and conceive screen work. I simply could not have done this project without my background and practice as a producer.

I did it! I am a Dr. The first in my family history! I write to tell you the news but more than that, to share some of my scholarly journey. But why write a letter you ask? Well, I must declare upfront that I do have an attraction to the epistolary form as a mode of self-expression. It was sparked by mother, a submissive type, who I watched as a child write cursive letters to her acquaintances on Sunday evenings. As I grew and we drifted, she would write to me over the years. It was her way of connecting, although I must say that her letters were never deep. They were hard to read and focused on the mundane, yet I sensed her desire to express herself. Her letters frustrated me, but there was something about the form that I was drawn to. Perhaps I longed to be able to communicate with her and for her to write the truth.

Did you know that the narrative form of letter writing became popularised by women during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries? Letters were seen as an acceptable form of communication back then, in which women could express themselves easily, offering little to no challenge to the chronicles of man.1 Do not worry, my letter to you will be more than an attempt at self-expression. At times I will include academic interludes, and most certainly you will get some potted personal history. I hope to at least achieve some of the characteristics of letter writing that Hallett describes as heartfelt, truthful, idealistic, moody, anxiety-ridden, manipulative, temporal, yet ‘of the moment.’2 By choosing this form my dear researcher, I am attempting to reflexively recount an auto/biographic experience of my PhD research journey. Yet, by making the choice to go with this genre, I am acutely aware of the ethical and epistemological implications of my decision:

The notion of auto/biography is linked to that of the ‘autobiographical I’. The auto/biographical I is an inquiring, analytic, sociological – here feminist sociological – agent who is concerned with constructing, rather than ‘discovering’ social reality and sociological knowledge. The use of ‘I’ explicitly recognizes that such knowledge is contextual, situational and specific, and that it will differ systematically according to the social location (as a gendered, raced, classed, sexualised, person) of the particular knowledge-producer.3

What I can only admit to as a slow, somewhat uneasy research process, ‘I’4 not only produced a multi-platform digital archive project, ‘I’ produced a multi-faceted version of self. I write this letter to you then as an experiential and contextual analysis of how I constructed and became a knowledge-producer of my research enquiry (into that of my practice and existential self). My hope is that as practice-researchers, you might be inspired to consider what is your construction of self and how it has influenced your research. For the non-practice researchers reading this, may this letter serve to advance your knowledge about how one’s practice can influence and support new knowledge.

But of course, as I write this, the anxiety that Hallett warned as evident to this form has begun to reveal itself; ‘(Will I achieve the right tone?’5 The obsession has begun. What happens when I send it? Will my words be dismissed as self-reflexive drivel? Will it be peer-reviewed? Will you reject me? Will I remain misunderstood? My attempt to connect with you may indeed fall flat. For how you receive my words is outside of my control, yet here I go…

When I entered the world of research, I had little depth and understanding of the actual term ‘research’. You see, I was more of a practitioner type back then and my modus operandi was to find out the information, decide on a course of action and move on. I was pragmatic, logical, and decisive (it was, and remains a rather efficient way to live my life).I struggled to make sense of why one would spend so much time investigating things without a clear result. Worse, was the idea that you could spend so much time researching something that may be disproved or eventuate to nothing. How mortifying!

Allow me to retrace my steps for you… I began working at the University of Melbourne, Victorian College of the Arts (VCA) Film and Television department in 2013 in a professional role. Here, I oversaw the administration and compliance of the student short films produced in the film department. I was known by staff as a ‘fixer’, a problem solver (dare I say, a woman of action?). I took on the responsibility for distribution deals related to the student films attracting the last vestiges of broadcast support. By the end of that year, Apple had stopped making its MacBook pro computers with DVD drives, and Blockbuster announced it was closing its DVD stores. Technology was killing the video store, and the need for VCA Film and Television to embrace online distribution and the digital access of its films, was fast becoming a pressing issue.

Students wanted to screen their films online and share their work easily amongst peers, beyond the traditional pathway of the film festival circuit. I became inspired by a staff member, who casually remarked one day that our department could solve these problems if it set up its very own YouTube channel. I decided to take on the project and swiftly enrolled into my masters, where some of you who are reading this letter will be situated. Within a year I converted to a doctoral degree, recalling the MFA supervisor stating that I was creating a lifetime job for myself at the institution. Little did I know that his words would begin to ring true, as seven years later the project continues to evolve.

Initially I chose to investigate the practicalities and challenges of designing and strategising a YouTube style internet channel for the VCA Film School—aptly titled VCATube. VCA held in its archive room, over 1,750 student films dating back to 1966, acknowledging its early lineage from Swinburne Technical College (now Swinburne University), marking it as Australia’s inaugural film school.6 I hope you don’t mind, but I feel I need to give you some further background knowledge to the institutional home of this project for this story to make more sense. In 1992, Swinburne amalgamated into VCA, before merging into the University of Melbourne and settling into the Faculty of Fine Arts and Music, where it currently resides. At the time of the consolidation, the audiovisual holdings were transferred to VCA, along with the ethos of the film school; practice-based filmmaking (learning by doing). Founder, Brian Robinson, had been inspired by the practice-based framework he observed whilst visiting the University of California in the 1960s.7 In the 1960s and 1970s, experimental modes of practice were common to arts making and became a popular form of filmmaking by students at the film school.8

In 2006, I had completed my postgraduate study in producing at VCA, and gained a deeper understanding of the blood, sweat and tears required to make student short films. Coupled with my industry experience, taking on a large-scale multi-platform project did not phase me, yet the academic research felt like an uncomfortable fit. You see, I was a producer and I produced content with an audience in mind. In case you do not know about the role of the film producer, Eve Honthaner, describes the job remit quite well:

A producer is basically the one who initiates, coordinates, supervises and controls all creative, financial, technological and administrative aspects of a motion picture and/or television show throughout all phases from inception to completion.9

To achieve a film, my goal has always been to bring together skilled players with their various expertise to realise the writer/director’s vision. So, when I heard of practice-led research, it made sense to me as a framework; the practice of filmmaking driving the research enquiry process. Yet I must confess, I did not understand why I needed to provide an argument for how I did things. Why should I lay claim to how I arrived at knowledge, particularly if it worked? Why over analyse and complicate things?

Over time, I discovered that the process of ‘doing’ was a legitimate form of research, so it was not surprising then that after making some headway in the ‘doing’ of the project, that I happened upon ‘action research’. You might be aware that there are many modes of action research (I will simplify from here as AR), and that it is a term coined by the social scientist Kurt Lewin in the 1950s. AR is used most often in the field of educational research, but can be very effective in participatory and arts based research (if you want to know more, I suggest hunting down Dick 1993; Zuber-Skerrit 1996; Whitehead and McNiff 2006; Greenwood and Levin 2011; Kemmis, McTaggart and Nixon 2014). Simply my friend, if it is okay to call you such, AR is a cyclical process that follows four steps; plan, act, observe, reflect.10 However, this redaction is defended by researchers such as McTaggart, who see AR as ‘…a series of commitments to observe and problematise through practice of a series of principles for conducting social enquiry.’11 Zuber-Skerritt asserts the objective of AR is ‘to bring about practical improvement, innovation, change or development of social practice, and the practitioners’ better understanding of their practices.’12

As I had come to the research from a practitioner’s perspective, I felt responsive to the idea of bringing about organisational change to better processes and practice. When I arrived at VCA, I had discovered a systematic problem—a situation that demanded responsiveness. Simply, no one could easily access the past films made by film students, unless they had a library card and DVD player. DVD was dying and the threat of format obsolescence ever pressing. Discovering this problem soon led to more than setting up a YouTube channel for the film school. Rather, it became an exploration of the challenges and stages of developing and producing a wide scale digitisation, preservation, and access digital archive research project for teaching, learning, research and engagement.

Allow me to digress to offer up a definition of the archive. The word archive derives from the Greek word ‘arkheion’ meaning a house; a domicile.13 Steedman says that inside its domicile ‘The Archive is made from selected and consciously chosen documentation from the past and also from the mad fragmentations that no one intended to preserve and that just ended up there.’14 Don’t you love this idea of mad fragmentations? It provokes in me the need to make some semblance of order. In the VCA Film and Television archive there were 16mm films, magnetic media (Digital Betacam, Betacam SP, HDCAM and Umatic magnetic tapes, a large collection of stills, catalogues and production paperwork associated with the making of the films). I am not sure how much you know about digitisation and the like, but to digitise a film means more than creating a digital version. It means producing multiple digital versions and formats that then need to be further archived in a digital repository with their associated metadata (data about data), to ensure their long-term value and accessibility.

The technical intricacies of an archive project are not dissimilar from the complexities of a film project. For filmmaking is made up of many parts and is inherently collaborative and interdisciplinary. Archives also need to connect with various disciplines, such as records management, library and computer science, through to new media and digital and cultural heritage preservation. As a producer on independent projects, I might wear several hats, and so too in the digital archive project, I found myself becoming a multiple operator. I played the role of pseudo archivist, record keeper and information management expert. Yet metadata muddled me, and the granular thinking required in these disciplines turned my stomach. I know, I know! I hear you thinking… the process of organisational change is slow and difficult! You are right. Research proves that it is conditional upon achieving several factors, which Zuber-Skerrit defines as:

… based on team collaboration, coordination, commitment and competence; and it needs to foster critical, double-loop learning in order to effect real change and emancipation, not only for the participants themselves, but also for the organization as a whole.15

I’ll be honest, I found it difficult to achieve any of these things within VCA Film and Television and the wider university. Lack of resourcing, time and conflicting schedules impeded on my ideal of setting up a collaborative and participatory based digital archive project.

Outside of the practical project, I felt overwhelmed and confused by the theory surrounding the practice. I was a big picture thinker (admittedly prone to internal flights of fancy). I struggled to give expression to complex thoughts and ideas. You might describe this my friend, as a form of imposter syndrome, but really, I was battling daily with negative self-talk and low self-esteem.

As I moved through the many action steps required to research and plan the project, new revelations dawned on me. AR, as a process of social enquiry and an attempt to gain a better understanding of one’s practice,16 meant that I was naturally inquiring into the way I was going about things. I discovered that I had been taking action to keep me from myself! Sure, I liked to plan, observe and share, but I struggled to reflect. The idea of being in my body and head long enough to notice what was going on, seemed foreign, incomprehensible and frankly, rather unpleasant (l will come back to this later, I promise…).

Firstly though, I want to give you a bit more context of this research to show you the breadth of the project and to assure you that the research was situated within a larger discourse of film preservation in Australia and internationally (the challenges I faced were not just about my inner world, they were also about audiovisual preservation). Lack of time, resourcing, equipment, and funding were the key problems cited in ensuring the large numbers of film and analogue material could be sufficiently digitised.17 There were issues of software and hardware progression, commerciality, cultural heritage, economic sustainability and risk management, among others. Add to this, the enormity of digital data and complex databases, plus the inability of local storage devices to accommodate these things,18 the digital archive project was formidable.

Don’t worry my friend, I achieved small wins along the way. As I moved pragmatically through the research journey, I discovered that I had been operating professionally as a screen producer with a tacit knowledge of my practice, what Donald Schon would describe as ‘knowing-in-practice.’19 My implicit understanding of my practice was in many ways a form of research, not yet made explicit. I reflected in action—through the act of asking questions, engaging with stakeholders, meetings, emails, notes. These simple acts informed each moment and became how I constructed knowledge and made meaning.

Let us pause momentarily here my dear researcher, as this is an important point. You see, I was beginning to realise that my ability to construct knowledge was indeed legitimate (you might already know this as a constructivist approach!).20 The process of research forced me to stop and reflect on my practice—how I operated and discovered knowledge for its translation.

As I began to tie together my methodology, combining action and filmmaking research, I saw that my process fitted in with Denzin’s method of interpretive interactionism. ‘The biographical, interpretive method rests on the collection, analysis, and performance of stories, accounts, and narratives that speak to turning-point moments in people's lives.’21 My inward reflexive process started to become unapologetically subjective as you are about to read.

As I began to articulate my research journey and explain meaning, my epistemic discoveries opened into a broader ontological discovery. I began to see that from an early age, I had been (re)constructing a sense of self, motivated by a desperate need to (re)build a fragmented identity borne out of being a survivor of extreme sexual and mental abuse. In the early years of my research, the process of ‘doing’ was so natural and easy to me. I produced task lists, milestones, project plans and funding applications. I took the project beyond a theoretical investigation and practically produced it. I led the digitisation, preservation and curation of over 1,750 student films, ensuring their accessibility on a university supported digital platform.

Yet, it wasn’t until years into the research, after the doing of the project, that I began to observe that I had not valued the practice of screen producing enough to consider it as a legitimate and justifiable mode of research. So, I drew on many forms of action research, all of which helped drive my line of inquiry, but the truth was, I kept falling back into my skills of producing, and the processes by which I would make and conceive screen work. I simply could not have done this project without my background and practice as a producer.

And this is what I hope you take

away from my letter. It was in the writing of my dissertation and reflecting on

the actions that I took, that I began to develop a greater awareness of my

ontological and epistemological stance to understand how I arrived at this

project and how I created new knowledge. I did this intuitively and creatively,

as I began to insert pieces of myself (documents of my personal history) into

the larger story of digitising and preserving an historic and culturally

significant audiovisual film school archive.

My first foray into inserting myself into the project came in 2015, after I published a short piece about the digital archive project in the University of Melbourne’s Cultural Collections Magazine. With the aid of the Film School, we had formalised the VCA Film and Television archive as a University Cultural Collection in 2014, due to its cultural, research, historical and aesthetic significance. In case you are not aware, the Cultural Collections Unit contains over thirty diverse collections from academic disciplines such as botany, dentistry, medicine, law, zoology and more and are made up of specimens, maps, medical and dental implants, paintings and rare books… but no moving image archives. Our collection proved to be unique and worth alerting the wider university about.

I then received a phone call from the editor at the online news publication, The Conversation. The news had broken that VHS players were no longer going to be manufactured. They asked me to write a response. I jumped at the opportunity and began to think about my history with VHS and realised that I had had a significant relationship with the format in my late teens. I had produced and directed my first film on VHS tape! Can you guess what I wrote as a response? A letter of course! I wrote a love letter to VHS:

I went home and dusted off my old VHS tapes and had them digitised. I laughed as I watched my early work, remembering the passion and zeal in which I had rallied my friends from my local church and school over a weekend to make my first poorly written horror short film, Reigning Terror. I was 16 and knew nothing about filmmaking, yet there I was again, constructing knowledge and developing my practice as I learnt through the process of doing and making mistakes. Those moments of watching and observing past actions allowed me to reflect on the process of my making:

Soon after, I wrote a narrative reflection about the project for the Australian Society of Archivists newsletter. This time, I turned to third person prose to express elements of my research journey:

I am telling you all this because as I began to insert myself into the narration of the digital archive project, each time I started to share a little more of myself. At a public event held at ACMI in 2017, titled Film and Data EXPOSED, the project team presented the first iteration of the digital archive portal to a research and industry audience. Here, I unashamedly admitted that I hated growing up. It pained me, even as a child, to know that one day when I was older, I would finally accept myself. I loathed having to endure the endless years of gritting through my early life, only to be bestowed some sort of relief that people over 35 assured me would come. With this impatience driving me, you can see that I was hardly nostalgic. I was unashamedly modern and fickle. I migrated from one thing—one medium to the next—making, mastering, moving on. Yet, psychologists purport that nostalgia contributes to positive social and personal development.25 So as the digital archive evolved, so too did my understanding of nostalgia. Of course, I had moved beyond remembering the first name of the first street I lived on and pairing it with my first pet’s name to work out my porn star identity (Tiger Uralla, in case you were wondering…). Instead, I began to see nostalgia more like what Gabriel describes as ‘a source of meaning in life’26 and as developing a sense of continuity between one’s past and present self.27 As I learned to recognise and give honour to my past self, it enabled me to connect to my present and future self—establishing the ontological awareness and epistemological framework in which to contain my research. I hope you are beginning to understand as I cannot help but wonder where you are at with this in your own research journey.

I can now see that I was in a process of coming out publicly as a survivor of childhood sexual abuse. I was writing my past into the present. Through the digitisation of the short films in the archive, I realised the memories from my childhood, fractured and full of terror, were also coming into light. My process of understanding self was not so dissimilar to the students whose films I was archiving. These early filmmakers were also revealing stories held within themselves and beginning to enter a world of political, cultural, religious or social discourse. Their work and identities, like mine, were unpolished, unformed, uncontextualised, unrefined. Yet within all our rawness, lay a sense of authenticity. The lack of polish refreshing in a world where everything is so well crafted to manipulate audiences in how they should think or feel. I think that students who make films are still finding, defining and creating their voice and unbeknownst to them, are often capturing the zeitgeist of the times.

Over time, my relationship and understanding of student film archives evolved. I realised our archive was much more than a showcase of the famous works of filmmakers who had gone on to contribute to the national and international filmmaking scene. Instead, it lay claim to a rich audiovisual social and cultural history of films by students who were exploring their identity and raising questions and concerns about their place in society. More than the filmmaker's curiosity, the films in our archive were a time capsule of its people, places and things rooted in the past. Locations had changed, suburbs had become gentrified. The cultural milieu of Melbourne transformed over decades, becoming more diverse and fascinating over time.

But alas, I am going on my friend, and I must begin to close this letter. Thank you for hanging in there. What has come of all this, you might be wondering? You will be pleased to know that the practical component of my research has culminated in the creation of a bespoke digital platform, which features over 2,000 student short films, dating back to 1966. Each film comes with rich filmographic metadata and is searchable through film-based keywords and nomenclature. The digital archive is a retrospective digital archive and a pipeline for all the current and future born-digital film works. This enables students, for the first time in the VCA Film and TV’s history to digitally store, archive, present and curate all the films they make whilst at film school. Films can be curated into collections for personal or public screening use. Students enter their own metadata, which means the collection is continually enlivened and activated through the submission of information to contextualise their work. This adds to the richness of the collection and builds on its cultural and historical significance. The short films are no longer static, they are truly digital moving images, which can be put into new contexts and transformed. The archive is more than a heritage site. It brings together past, present and future.

There are so many things I could have talked to you about my dear researcher. In this letter to you, I have attempted to convey some of the dynamic and evolving space of the archive. As we are in networked age characterised by flux and connection, I must admit that I am worried about the future of the collection. To ensure the collection grows and thrives, VCA must continue to migrate, back up and digitally housekeep. If this doesn’t happen, then the files and interface will become redundant, just like what was happening to the magnetic tapes and film reels. My concerns as to how you will interpret this letter have at least evolved to something larger than myself. For now, the digital archive project remains a complete research project, but one that is very much ongoing. It is a site of transformation, whereby a large, short film collection was transformed from old technology into new. It is a platform where knowledge is housed and translated by, with and for film students and the research community. My research offers insight into how these transformations took place. Now that the collection is digitally available, my hope is that its users can evolve its usage in ways that I cannot predict.

As for me? Well, in (re)creating and producing the digital archive, ‘I’28 (re)created and produced myself—moving from an identity rooted in shame and the toxic effects of childhood sexual abuse, to one of post-traumatic growth. This letter to you is another part of the archive’s holdings. In many ways, the digital archive is a collection of ‘mad fragments’29 of my life. It has traced aspects of my childhood, my early filmmaking career and educational pursuits. Through the process of action, reflection and subjective interpretation, it has opened my understanding of, and situated various, epistemological methods and beliefs. This has had implications for developing a deeper understanding of my ontological self. Through my journey, I have become aware of how I came to (re)assemble a sense of self, constructing fragments of my identity, through my practice and in co-creating myself in relationship with others. This has led to the legitimisation and authentication of my scholarly identity. I can assure you it has also positively impacted my professional, artistic and personal pursuits, which I hope will be the same for you. Articulating and explicating my knowledge journey has been transformative, profound, and emancipatory, just like all good action research projects should be. Kemmis says the tell-tale signs of whether something or someone has been emancipated yet, is answering the question ‘are things better than they were?’, not, ‘Are we emancipated yet?’.30

I tell you my friend, yes! VCA Film and Television has changed because of this project. Institutional and student film practice has changed. I have changed. My practice has changed, my understanding of my practice has changed. Derrida and Prenowitz ask; ‘As much as and more than a thing of the past, before such a thing, the archive should call into question the coming of the future.’31 So, I am curious then, who you will be as you continue in your research journey. Who were you? Who are you now? Where will you go? Who will you become?

Yours Sincerely,

Dr. Donna Lyon

ps. Don’t forget to do your RIOT training asap.

pps. Learn how to reference properly from the start.

ppps. Do try and locate your ontological position and epistemological beliefs as a first action step.

pppps. And remember to check out the digital archive. https://finearts-music.unimelb.edu.au/digital-archive

Notes:

1. Katherine Carroll, ‘Representing Ethnographic Data Through the Epistolary Form,’ Qualitative Inquiry, 21, no. 8 (2015), https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800414566691,https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1077800414566691, 686.

2. Nicky Hallett in SAGE Biographical Research. 4 vols. ed. John Goodwin (London; SAGE Publications, 2012, https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446268537,https://methods.sagepub.com/book/sage-biographical-research, 3.

3. Liz Stanley in SAGE Biographical Research. 4 vols. ed. John Goodwin (London; SAGE Publications, 2012, https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446268537,https://methods.sagepub.com/book/sage-biographical-research, 10.

4. In this early phase of the research, ‘I’ refers to me as a white, able-bodied, middle class cis-gender bisexual feminist. ‘I’ as film producer and practitioner. ‘I’ as adult child estranged from her parents.

5. Hallett, ‘SAGE Biographical Research,’ 2.

6. To give you some further context here, VCA Film and Television has launched the careers of numerous acclaimed filmmakers, including Robert Luketic (Legally Blonde), David Michod (Animal Kingdom), Michael Henry (Blame),Justin Kurzel (Snowtown, MacBeth), Jonathan Auf der Heide (Van Diemen's Land),Richard Gray (Summer Coda), Gillian Armstrong (Love, Lust and Lies) and Oscar Winner, Adam Elliot (Harvey Krumpet, Mary and Max) and more recently, Ariel Kleiman (Partisan), Kitty Green (Ukraine is Not a Brothel, Casting Jon Benet), Alethea Jones (Fun, Mom, Dinner), Polly Staniford (Berlin Syndrome, Lion).

7. Barbara Paterson, Renegades: Australia's First Film School from Swinburne to VCA (Victoria, Australia: The Helicon Press, 1996), 47.

8. Paterson, Renegades: Australia's First Film School from Swinburne to VCA, 49.

9. Eve Light Honthaner, The Complete Film Production Handbook, 4th ed. (USA: Elsevier Inc., 2010), 2.

10. Bob Dick, ‘You want to do an action research thesis? — How to conduct and report action research. (Including a beginner’s guide to the literature),’ action research theses (Resource), 1993, http://www.aral.com.au/resources/arthesis.html#a_art_whatisar.

11. Robyn McTaggart, in New Directions in Action Research, ed. Ortrun Zuber-Skerritt (London; Washington, D.C.: Falmer Press, 1996), 248.

12. Ortrun Zuber-Skerritt, New Directions in Action Research, 1st ed. (London; Washington, D.C.: Falmer Press, 1996), 83.

13. Jacques Derrida and Eric Prenowitz, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, (Baltimore, Maryland:The Johns Hopkins University Press 25, no. 2 1995), http://www.jstor.org/stable/465144, 9.

14. Carolyn Steedman, Dust(Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2001), 68.

15. Zuber-Skerritt, New Directions in Action Research, 95.

16. Stephen Kemmis, Robin McTaggart, and Rhonda Nixon, The Action Research Planner, (Singapore; Heidelberg; New York; Dordrecht; London.: Springer Publishing, 2014), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-4560-67-2.

17. Jon Wengstrom, ‘Access to film heritage in the digital era – Challenges and opportunities,’ HÖGSKOLAN I BORÅS, NORDISK KULTURPOLITISK TIDSKRIFT 16, no. 1 (2013), www.idunn.no.

18. Ray Edmondson, Audiovisual Archiving, 3 ed. (Paris: The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation, 2016). https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000243973_tha.

19. Donald A. Schon, The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action (England: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 1991, 1983).

20. Liane V. Davis, ‘Feminism and Constructivism,’ Journal of Teaching in Social Work 8, no. 1-2 (2008), https://doi.org/https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1300/J067v08n01_08.

21. Denzin, Norman K. "Securing Biographical Experience." In Interpretive Interactionism, 2nd ed., ,57-69. , Applied Social Research Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc., 2001. http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781412984591.

22. Donna Lyon, ‘Magnetic memoir: a love letter to VHS from the archives,’ The Conversation, 2016, https://theconversation.com/magnetic-memoir-a-love-letter-to-vhs-from-the-archives-63759.

23. Lyon, ‘Magnetic memoir: a love letter to VHS from the archives.’

24. Donna Lyon, ‘A short story about magnetic memories; caverns of celluloid; and making meaning,’ Australian Society of Archivists (Online Newsletter), 2018, https://www.archivists.org.au/documents/item/1304.

25. Constantine Sedikides and Tim Wildschut, ‘Finding Meaning in Nostalgia,’ Review of General Psychology 22, 48–61. (2018) doi:10.1037/gpr0000109.

26. Gabriel (1993, 137) in Constantine Sedikides and Tim Wildschut, ‘Finding Meaning in Nostalgia,’ Review of General Psychology 22, 48–61. (2018) doi:10.1037/gpr0000109, 50.

27. Sedikides and Wildschut, ‘Finding Meaning in Nostalgia.’

28. In this final phase of the research, ‘I’ now refers to me as a white, middle class cis-gender bisexual feminist. ‘I’ as adult child estranged from her parents. ‘I’ as survivor of childhood sexual abuse, ‘I’ as film producer, ‘cultural agent’ and pracademic, situated on the lands of the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin nation.

29. Carolyn Steedman, Dust (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2001).

30. Kemmis, McTaggart, and Nixon, ‘The Action Research Planner,’ 245.

31. Derrida and Prenowitz, ‘Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression,’ 26.

About the author:

Donna Lyon is a screen educator, PhD practice-led researcher and producer, who has recently produced the independent feature film Disclosure. Her research has been focused on the digitisation, preservation, and dissemination of the historic and culturally significant VCA student film archive. Alongside ‘doing’ the project, she inserted herself into the digitization of the ‘works’, to create a holistic, personal, engaged, and reflexive strategy to expand existing notions of archives and to examine the practice of producing the archive. You can request access to the digital archive HERE.

My first foray into inserting myself into the project came in 2015, after I published a short piece about the digital archive project in the University of Melbourne’s Cultural Collections Magazine. With the aid of the Film School, we had formalised the VCA Film and Television archive as a University Cultural Collection in 2014, due to its cultural, research, historical and aesthetic significance. In case you are not aware, the Cultural Collections Unit contains over thirty diverse collections from academic disciplines such as botany, dentistry, medicine, law, zoology and more and are made up of specimens, maps, medical and dental implants, paintings and rare books… but no moving image archives. Our collection proved to be unique and worth alerting the wider university about.

I then received a phone call from the editor at the online news publication, The Conversation. The news had broken that VHS players were no longer going to be manufactured. They asked me to write a response. I jumped at the opportunity and began to think about my history with VHS and realised that I had had a significant relationship with the format in my late teens. I had produced and directed my first film on VHS tape! Can you guess what I wrote as a response? A letter of course! I wrote a love letter to VHS:

I stayed late after school editing you all together. You captured my vision; you finished my vision – you were my master… tape. You were solid, real and fun to carry and put in the machine. I understood you. I made other movies with you too before I graduated and moved on to more mature models, like Super VHS and Betacam. But I never forgot you. You were my first.22

I went home and dusted off my old VHS tapes and had them digitised. I laughed as I watched my early work, remembering the passion and zeal in which I had rallied my friends from my local church and school over a weekend to make my first poorly written horror short film, Reigning Terror. I was 16 and knew nothing about filmmaking, yet there I was again, constructing knowledge and developing my practice as I learnt through the process of doing and making mistakes. Those moments of watching and observing past actions allowed me to reflect on the process of my making:

I sat watching my work from 16 to 19 years old – a true blast from the past. It had been years since I had seen you. The images spoke of an unconscious grappling with the trauma I was now working on in therapy. I was using you as an early recovery tool; a healing tool.23

Soon after, I wrote a narrative reflection about the project for the Australian Society of Archivists newsletter. This time, I turned to third person prose to express elements of my research journey:

One afternoon, two archivists stopped by. She showed them the archive room and watched with curiosity as their eyes lit up and tongues began to salivate. With their noses in the air, they said, matter of fact: ‘this room smells like vinegar’. The woman had encountered her first problem. Later, she mused that the archivists were a strange breed, but they had her thinking. She began to reflect ever so slightly on audiovisual heritage and cultural memory. Nostalgia had crept in.24

I am telling you all this because as I began to insert myself into the narration of the digital archive project, each time I started to share a little more of myself. At a public event held at ACMI in 2017, titled Film and Data EXPOSED, the project team presented the first iteration of the digital archive portal to a research and industry audience. Here, I unashamedly admitted that I hated growing up. It pained me, even as a child, to know that one day when I was older, I would finally accept myself. I loathed having to endure the endless years of gritting through my early life, only to be bestowed some sort of relief that people over 35 assured me would come. With this impatience driving me, you can see that I was hardly nostalgic. I was unashamedly modern and fickle. I migrated from one thing—one medium to the next—making, mastering, moving on. Yet, psychologists purport that nostalgia contributes to positive social and personal development.25 So as the digital archive evolved, so too did my understanding of nostalgia. Of course, I had moved beyond remembering the first name of the first street I lived on and pairing it with my first pet’s name to work out my porn star identity (Tiger Uralla, in case you were wondering…). Instead, I began to see nostalgia more like what Gabriel describes as ‘a source of meaning in life’26 and as developing a sense of continuity between one’s past and present self.27 As I learned to recognise and give honour to my past self, it enabled me to connect to my present and future self—establishing the ontological awareness and epistemological framework in which to contain my research. I hope you are beginning to understand as I cannot help but wonder where you are at with this in your own research journey.

I can now see that I was in a process of coming out publicly as a survivor of childhood sexual abuse. I was writing my past into the present. Through the digitisation of the short films in the archive, I realised the memories from my childhood, fractured and full of terror, were also coming into light. My process of understanding self was not so dissimilar to the students whose films I was archiving. These early filmmakers were also revealing stories held within themselves and beginning to enter a world of political, cultural, religious or social discourse. Their work and identities, like mine, were unpolished, unformed, uncontextualised, unrefined. Yet within all our rawness, lay a sense of authenticity. The lack of polish refreshing in a world where everything is so well crafted to manipulate audiences in how they should think or feel. I think that students who make films are still finding, defining and creating their voice and unbeknownst to them, are often capturing the zeitgeist of the times.

Over time, my relationship and understanding of student film archives evolved. I realised our archive was much more than a showcase of the famous works of filmmakers who had gone on to contribute to the national and international filmmaking scene. Instead, it lay claim to a rich audiovisual social and cultural history of films by students who were exploring their identity and raising questions and concerns about their place in society. More than the filmmaker's curiosity, the films in our archive were a time capsule of its people, places and things rooted in the past. Locations had changed, suburbs had become gentrified. The cultural milieu of Melbourne transformed over decades, becoming more diverse and fascinating over time.

But alas, I am going on my friend, and I must begin to close this letter. Thank you for hanging in there. What has come of all this, you might be wondering? You will be pleased to know that the practical component of my research has culminated in the creation of a bespoke digital platform, which features over 2,000 student short films, dating back to 1966. Each film comes with rich filmographic metadata and is searchable through film-based keywords and nomenclature. The digital archive is a retrospective digital archive and a pipeline for all the current and future born-digital film works. This enables students, for the first time in the VCA Film and TV’s history to digitally store, archive, present and curate all the films they make whilst at film school. Films can be curated into collections for personal or public screening use. Students enter their own metadata, which means the collection is continually enlivened and activated through the submission of information to contextualise their work. This adds to the richness of the collection and builds on its cultural and historical significance. The short films are no longer static, they are truly digital moving images, which can be put into new contexts and transformed. The archive is more than a heritage site. It brings together past, present and future.

There are so many things I could have talked to you about my dear researcher. In this letter to you, I have attempted to convey some of the dynamic and evolving space of the archive. As we are in networked age characterised by flux and connection, I must admit that I am worried about the future of the collection. To ensure the collection grows and thrives, VCA must continue to migrate, back up and digitally housekeep. If this doesn’t happen, then the files and interface will become redundant, just like what was happening to the magnetic tapes and film reels. My concerns as to how you will interpret this letter have at least evolved to something larger than myself. For now, the digital archive project remains a complete research project, but one that is very much ongoing. It is a site of transformation, whereby a large, short film collection was transformed from old technology into new. It is a platform where knowledge is housed and translated by, with and for film students and the research community. My research offers insight into how these transformations took place. Now that the collection is digitally available, my hope is that its users can evolve its usage in ways that I cannot predict.

As for me? Well, in (re)creating and producing the digital archive, ‘I’28 (re)created and produced myself—moving from an identity rooted in shame and the toxic effects of childhood sexual abuse, to one of post-traumatic growth. This letter to you is another part of the archive’s holdings. In many ways, the digital archive is a collection of ‘mad fragments’29 of my life. It has traced aspects of my childhood, my early filmmaking career and educational pursuits. Through the process of action, reflection and subjective interpretation, it has opened my understanding of, and situated various, epistemological methods and beliefs. This has had implications for developing a deeper understanding of my ontological self. Through my journey, I have become aware of how I came to (re)assemble a sense of self, constructing fragments of my identity, through my practice and in co-creating myself in relationship with others. This has led to the legitimisation and authentication of my scholarly identity. I can assure you it has also positively impacted my professional, artistic and personal pursuits, which I hope will be the same for you. Articulating and explicating my knowledge journey has been transformative, profound, and emancipatory, just like all good action research projects should be. Kemmis says the tell-tale signs of whether something or someone has been emancipated yet, is answering the question ‘are things better than they were?’, not, ‘Are we emancipated yet?’.30

I tell you my friend, yes! VCA Film and Television has changed because of this project. Institutional and student film practice has changed. I have changed. My practice has changed, my understanding of my practice has changed. Derrida and Prenowitz ask; ‘As much as and more than a thing of the past, before such a thing, the archive should call into question the coming of the future.’31 So, I am curious then, who you will be as you continue in your research journey. Who were you? Who are you now? Where will you go? Who will you become?

Yours Sincerely,

Dr. Donna Lyon

ps. Don’t forget to do your RIOT training asap.

pps. Learn how to reference properly from the start.

ppps. Do try and locate your ontological position and epistemological beliefs as a first action step.

pppps. And remember to check out the digital archive. https://finearts-music.unimelb.edu.au/digital-archive

Notes:

1. Katherine Carroll, ‘Representing Ethnographic Data Through the Epistolary Form,’ Qualitative Inquiry, 21, no. 8 (2015), https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800414566691,https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1077800414566691, 686.

2. Nicky Hallett in SAGE Biographical Research. 4 vols. ed. John Goodwin (London; SAGE Publications, 2012, https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446268537,https://methods.sagepub.com/book/sage-biographical-research, 3.

3. Liz Stanley in SAGE Biographical Research. 4 vols. ed. John Goodwin (London; SAGE Publications, 2012, https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446268537,https://methods.sagepub.com/book/sage-biographical-research, 10.

4. In this early phase of the research, ‘I’ refers to me as a white, able-bodied, middle class cis-gender bisexual feminist. ‘I’ as film producer and practitioner. ‘I’ as adult child estranged from her parents.

5. Hallett, ‘SAGE Biographical Research,’ 2.

6. To give you some further context here, VCA Film and Television has launched the careers of numerous acclaimed filmmakers, including Robert Luketic (Legally Blonde), David Michod (Animal Kingdom), Michael Henry (Blame),Justin Kurzel (Snowtown, MacBeth), Jonathan Auf der Heide (Van Diemen's Land),Richard Gray (Summer Coda), Gillian Armstrong (Love, Lust and Lies) and Oscar Winner, Adam Elliot (Harvey Krumpet, Mary and Max) and more recently, Ariel Kleiman (Partisan), Kitty Green (Ukraine is Not a Brothel, Casting Jon Benet), Alethea Jones (Fun, Mom, Dinner), Polly Staniford (Berlin Syndrome, Lion).

7. Barbara Paterson, Renegades: Australia's First Film School from Swinburne to VCA (Victoria, Australia: The Helicon Press, 1996), 47.

8. Paterson, Renegades: Australia's First Film School from Swinburne to VCA, 49.

9. Eve Light Honthaner, The Complete Film Production Handbook, 4th ed. (USA: Elsevier Inc., 2010), 2.

10. Bob Dick, ‘You want to do an action research thesis? — How to conduct and report action research. (Including a beginner’s guide to the literature),’ action research theses (Resource), 1993, http://www.aral.com.au/resources/arthesis.html#a_art_whatisar.

11. Robyn McTaggart, in New Directions in Action Research, ed. Ortrun Zuber-Skerritt (London; Washington, D.C.: Falmer Press, 1996), 248.

12. Ortrun Zuber-Skerritt, New Directions in Action Research, 1st ed. (London; Washington, D.C.: Falmer Press, 1996), 83.

13. Jacques Derrida and Eric Prenowitz, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, (Baltimore, Maryland:The Johns Hopkins University Press 25, no. 2 1995), http://www.jstor.org/stable/465144, 9.

14. Carolyn Steedman, Dust(Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2001), 68.

15. Zuber-Skerritt, New Directions in Action Research, 95.

16. Stephen Kemmis, Robin McTaggart, and Rhonda Nixon, The Action Research Planner, (Singapore; Heidelberg; New York; Dordrecht; London.: Springer Publishing, 2014), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-4560-67-2.

17. Jon Wengstrom, ‘Access to film heritage in the digital era – Challenges and opportunities,’ HÖGSKOLAN I BORÅS, NORDISK KULTURPOLITISK TIDSKRIFT 16, no. 1 (2013), www.idunn.no.

18. Ray Edmondson, Audiovisual Archiving, 3 ed. (Paris: The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation, 2016). https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000243973_tha.

19. Donald A. Schon, The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action (England: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 1991, 1983).

20. Liane V. Davis, ‘Feminism and Constructivism,’ Journal of Teaching in Social Work 8, no. 1-2 (2008), https://doi.org/https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1300/J067v08n01_08.

21. Denzin, Norman K. "Securing Biographical Experience." In Interpretive Interactionism, 2nd ed., ,57-69. , Applied Social Research Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc., 2001. http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781412984591.

22. Donna Lyon, ‘Magnetic memoir: a love letter to VHS from the archives,’ The Conversation, 2016, https://theconversation.com/magnetic-memoir-a-love-letter-to-vhs-from-the-archives-63759.

23. Lyon, ‘Magnetic memoir: a love letter to VHS from the archives.’

24. Donna Lyon, ‘A short story about magnetic memories; caverns of celluloid; and making meaning,’ Australian Society of Archivists (Online Newsletter), 2018, https://www.archivists.org.au/documents/item/1304.

25. Constantine Sedikides and Tim Wildschut, ‘Finding Meaning in Nostalgia,’ Review of General Psychology 22, 48–61. (2018) doi:10.1037/gpr0000109.

26. Gabriel (1993, 137) in Constantine Sedikides and Tim Wildschut, ‘Finding Meaning in Nostalgia,’ Review of General Psychology 22, 48–61. (2018) doi:10.1037/gpr0000109, 50.

27. Sedikides and Wildschut, ‘Finding Meaning in Nostalgia.’

28. In this final phase of the research, ‘I’ now refers to me as a white, middle class cis-gender bisexual feminist. ‘I’ as adult child estranged from her parents. ‘I’ as survivor of childhood sexual abuse, ‘I’ as film producer, ‘cultural agent’ and pracademic, situated on the lands of the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin nation.

29. Carolyn Steedman, Dust (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2001).

30. Kemmis, McTaggart, and Nixon, ‘The Action Research Planner,’ 245.

31. Derrida and Prenowitz, ‘Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression,’ 26.

About the author:

Donna Lyon is a screen educator, PhD practice-led researcher and producer, who has recently produced the independent feature film Disclosure. Her research has been focused on the digitisation, preservation, and dissemination of the historic and culturally significant VCA student film archive. Alongside ‘doing’ the project, she inserted herself into the digitization of the ‘works’, to create a holistic, personal, engaged, and reflexive strategy to expand existing notions of archives and to examine the practice of producing the archive. You can request access to the digital archive HERE.

Galaw-nilay: Articulating

Interiority in Meditative Movement

Rina Angela Corpus

To cite this contribution:

Corpus, Rina. ‘Galaw-nilay: Articulating Interiority in Meditative Movement’. Currents Journal Issue Two (2021), https://currentsjournal.net/Galaw-nilay-Articulating Interiority-in-Meditative-Movement.

Download this article ︎︎︎PDF

Course of study:

Doctor of Philosophy, Faculty of Fine Arts and Music (Dance), University of Melbourne

Keywords:

interiority, meditative movement, baybayin, galaw-nilay, somatics, screendance, Kristin Jackson, Philippine dance

Abstract: This article is dedicated to narrating the artistic process and intentions behind the creation of the short dance film, Still One, which is part of my performance portfolio for my PhD in Dance. It is based on my PhD research, which investigates interiority as a key element in meditative movement practice—mining its potential not just as a source of movement-material but as a locus of experience and creative expression. I call it galaw-nilay, an iteration of meditative movement through Philippine language. Galaw is Filipino for ‘movement’ and nilay means ‘to meditate or contemplate’. Galaw-nilay is a somatic proposition which refers to a practice of self-attunement and awareness to access interiority as a means for dance preparation and movement generation. In my broader research, I define the somatic-affective experience of galaw-nilay, exploring the affective qualities of the term drawn from local language through my corporeal and experiential archive. I use the solos of Filipina-American choreographer Kristin Jackson as a case study for my iteration of the interior in meditative movement, and I also define my own creative practice and dance in film

interiority, meditative movement, baybayin, galaw-nilay, somatics, screendance, Kristin Jackson, Philippine dance

Abstract: This article is dedicated to narrating the artistic process and intentions behind the creation of the short dance film, Still One, which is part of my performance portfolio for my PhD in Dance. It is based on my PhD research, which investigates interiority as a key element in meditative movement practice—mining its potential not just as a source of movement-material but as a locus of experience and creative expression. I call it galaw-nilay, an iteration of meditative movement through Philippine language. Galaw is Filipino for ‘movement’ and nilay means ‘to meditate or contemplate’. Galaw-nilay is a somatic proposition which refers to a practice of self-attunement and awareness to access interiority as a means for dance preparation and movement generation. In my broader research, I define the somatic-affective experience of galaw-nilay, exploring the affective qualities of the term drawn from local language through my corporeal and experiential archive. I use the solos of Filipina-American choreographer Kristin Jackson as a case study for my iteration of the interior in meditative movement, and I also define my own creative practice and dance in film

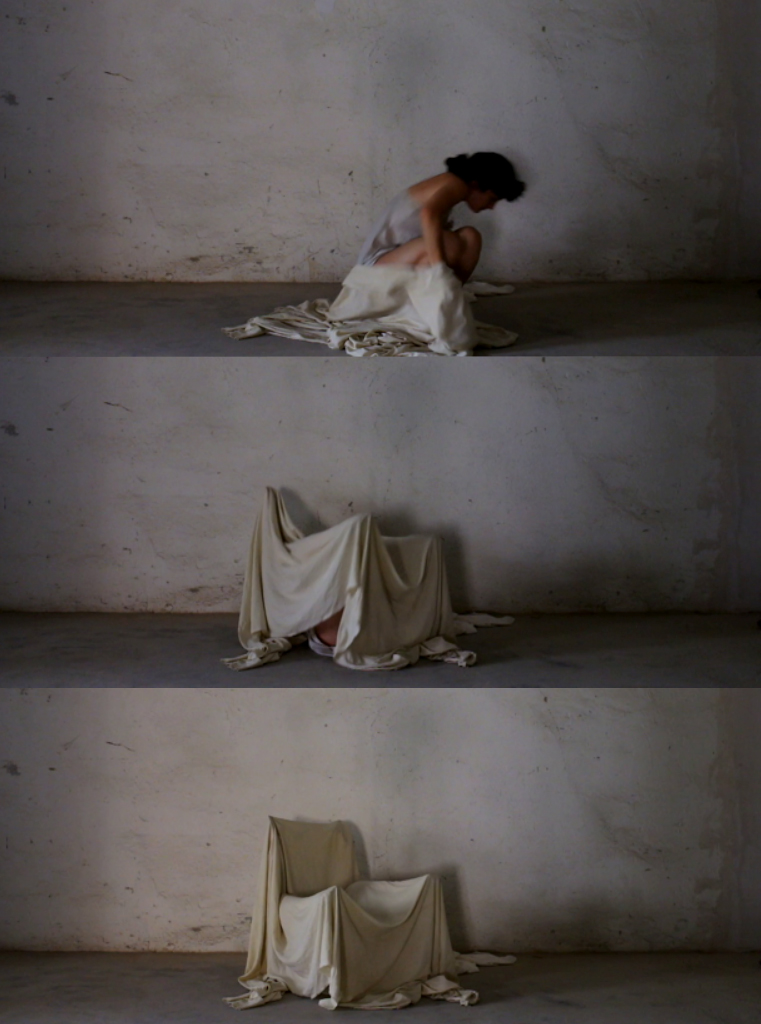

Image ^^^ Tracing letters from the baybayin with my arms and hands. Video still from, Still One (2020), Rina Angela Corpus co-directed with Antonne Santiago.

She begins the day

centered

In a space behind her thoughts

A silent witness to herself.

She wears a raiment of white

Navigating soundlessly to

A world beyond this one,

A place she has always known.

Sa ibayo, kung saan walang

kawayan, hangin,

dagat, ulap.1

She graces a world

beyond the dancing elements

of her earth. Her mind

relocating into a subtle skyscape

where a constellation of wonder

conspires to speak only one

blessed language:

Silence.

Infinitesimal star

she becomes

a mirror of light

from an eternal source,

incandescent.

Taking her fill

she emerges

sweetened in awareness

mind luminescent

Returning from her secret

voyage, she steps on terra firma

once more,

Brightened

by that silent, still one.2

This article narrates the artistic process and intentions behind the creation of the short dance film, Still One (2020). The essay is part of a broader research project that investigates interiority as a key element in meditative movement practice, considering its potential not just as a source of movement-material but as a locus of experience and creative expression. I define ‘interiority’ in dance as communing with the silent and still spaces of one’s inner life, drawing from my meditative practices of Raja yoga and Qigong. Raja yoga is a seated form of meditation while Qigong is an ancient Chinese movement art; both are attentional practices that articulate a sense of communion and attunement between body-mind-spirit.3 They also use and draw from an interior life, using concepts of silence and still moments to access one’s internal, physical, creative and psychic resources.

I call my specific practice of interiority in dance galaw-nilay, an iteration of meditative movement through Philippine language. Galaw is Filipino for ‘movement’ and nilay means ‘to meditate or contemplate’. Galaw-nilay is a somatic proposition that encompasses a practice of self-attunement and awareness, to access interiority as a means for dance preparation and movement generation. The words explored in this article give a sample of how local Philippine cultural wordings can be expressed and resonate through somatic experiences of movement and self-attunement. The terms I offer here are from my own language usage/coinage, following my native use of Filipino in conjunction with consulting Philippine academic colleagues who have offered me other possible terms.4 I know that there are some movement terms that still exist, especially in the regions outside the Philippine capital of Manila, but a wider understanding of such terms would require an additional movement-linguistic project beyond the scope of this current research. The Philippines has more than 170 languages, which makes the task of finding local wordings a challenge because of the linguistic diversity of the culture. Furthermore, many of the dance terms used in the Philippines have been acculturated from colonial, particularly Spanish-American, sources. There are few movement practitioners who use Filipino words in teaching movement, or they have not been extensively documented.5 This research is an initial attempt to incorporate local Philippine linguistic and cultural understandings into the field of meditative movement and dance.