Archipelagic Encounters

Zoya Chaudhary

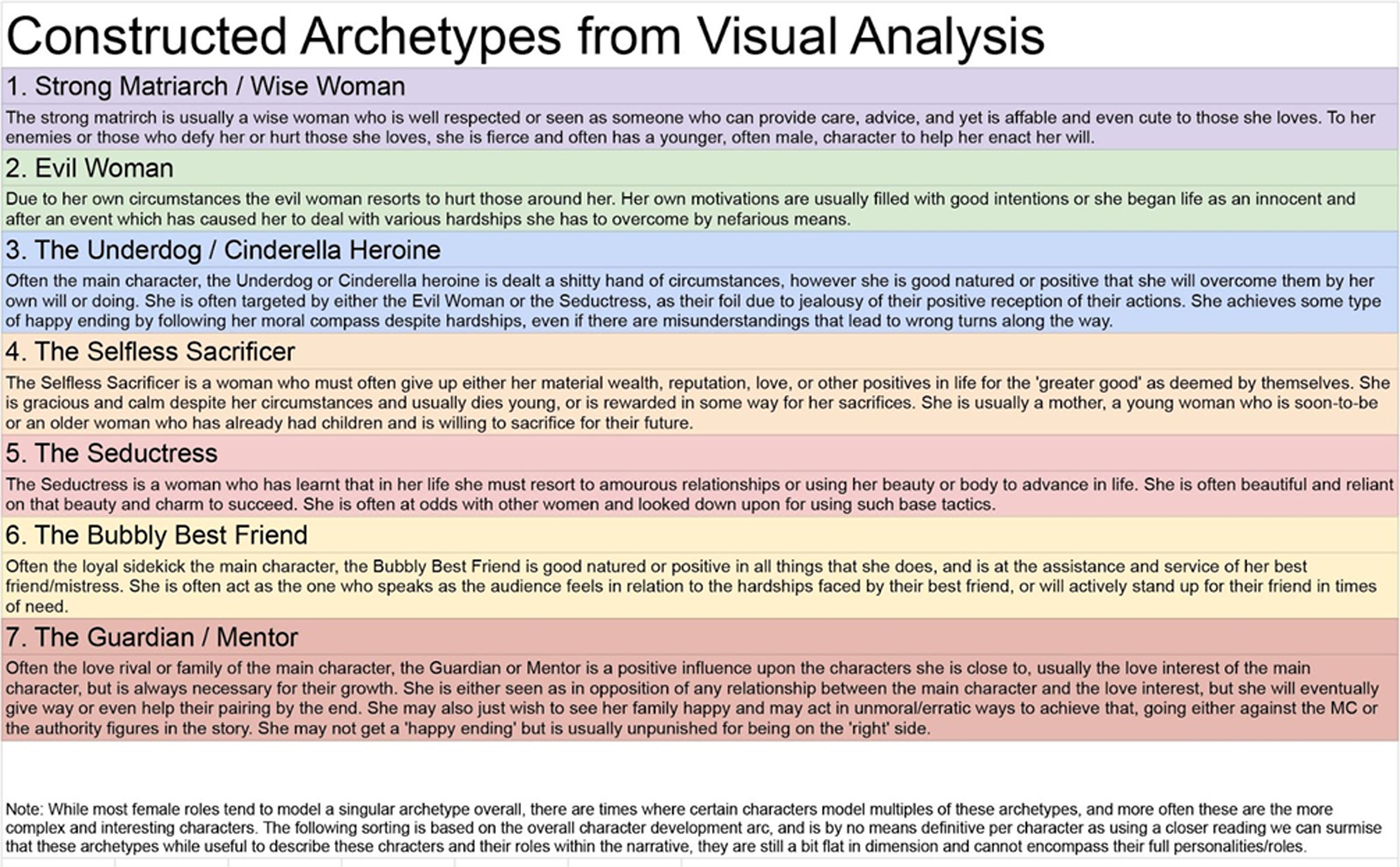

explores ‘media as material’ to demarcate the distance between lived experience and news media in a series of intricate artworks based on traditional Jali, Duncan Caillard explores the contemporary practice of Apichatpong Weerasethakul, analysing his installation SLEEPCINEMAHOTEL from 2018, Lizzie Wee

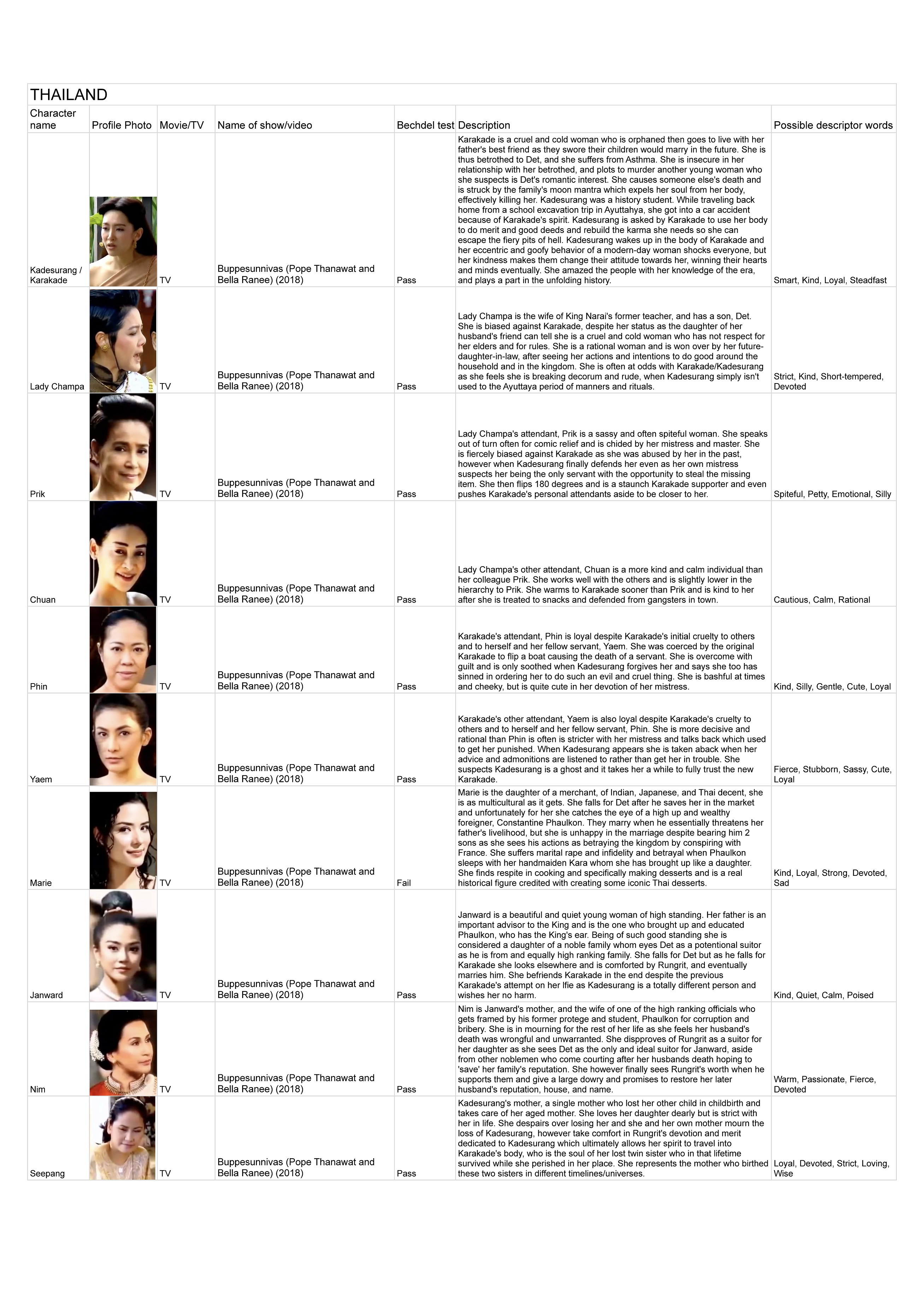

constructs a series of videos that map and perform archetypes of the ‘Southeast Asian female’ derived from televisual culture, Nurdiana Rahmat applies an intersectional feminist lens to Malay women artists contribution to Singapore’s art history, Kezia Yap retraces her cultural genealogy by translating Chinese scripts into music scores challenging conventions of Western music and assumptions of authentic ‘Chineseness’, Genevieve Trail analyses the spatial work of Choi Yan Chi prior to, and in the context of, increased political tensions in Hong Kong throughout the 1980s and Pratibha Nambiar employs spice-infused soap in labour intensive wall drawings to bring ritualistic domestic labour of the Indian household to the fore.

Contents

- Introduction — Elyssia Bugg, Jeremy Eaton and Chloe Ho

- Shaping Perception: Negotiating media as material, the fragility of time and fleeting emotions — Zoya Chaudhary

- Terms and Conditions: Re-examining Singapore Art History Through the Art Making Experiences of Early Malay Women Artists — Nurdiana Rahmat

- 这是妈妈. 这是爸爸.: an experiment in translation — Kezia Yap

- A Fugitive Subjectivity: Choi Yan Chi 蔡仞姿 and experimental art of Hong Kong, 1970-1989 — Genevieve Trail

- Performing the Domestic Ritualistic Mark — Pratibha Nambiar

Introduction –

Elyssia Bugg, Jeremy Eaton and Chloe Ho

To cite this contribution;

Bugg, Elyssia, Jeremy Eaton and Chloe Ho. ‘Archipelagic Encounters Introduction –’ Currents Journal, Archipelagic Encounters (2021), https://currentsjournal.net/archipelagic-encounters-introduction.

Download this article ︎︎︎PDF

Throughout the global south and across Southeast Asia the vast archipelagos of the Indian Ocean, the South China Sea and the Western Pacific, a region comprising over 25,000 islands, we see an array of distinct yet epistemically related cultural practices proliferate. It is a network constantly in a state of transformation, characterised by both a spatial and cultural mobility that has only intensified (up until quite recently) over the last decade. In his article Island Movements: Thinking with the Archipelago Jonathan Pugh considers how we might think with the ‘fluid island-island inter-relations’ to better understand how archipelagos as spatial networks, multiplicities and assemblages act as ‘generative and inter-connective spaces of metamorphosis, of material practices, culture and politics.’1 They are spaces defined by an unravelling set of cultural encounters that challenge western understandings of space, destablising centre and periphery dichotomies, as well as the perceived ‘territorial containers’ of political ideals and ethical categories.2 Thinking archipelagically from the Carribean, Édouard Glissant notes that ‘each island embodies openness. The dialectic between inside and outside is reflected in the relationship of land and sea.’3 Archipelagic Encounters, in-line with Pughes and Glissant, thinks with and through the archipelago, engaging early career researchers whose work reflects diverse networked relations between artistic practices and art histories that move across and within the Asia-Pacific.

This special issue was initiated by a symposium organised by the Centre of Visual Arts (CoVA), University of Melbourne and McNally School of Fine Arts, LASALLE College of the Arts of the same name in 2020. Set against the backdrop of the pandemic whereby national borders had closed and the international mobility that the region had become accustomed to suddenly ceased, we had to reconsider what it meant to be part of an archipelago and to encounter through an island geography. Boundaries that were once open, porous and frequently traversed, dissolved. There was no longer an inside and outside in the way described by Glissant, merely land masses that confined our existence and bodies of water that split and demarcated No Man’s Land. Pugh’s island-island relations, which assumed a physical migration of human bodies across islands, were cut. In Melbourne, mobility narrowed to a 5-km radius. The inside and outside of 2020 was the relationship between residential homes, public parks and the grocery store. A similar narrowing happened in the highly built-up Singapore. Residents were asked to stay within their own neighbourhoods and only go out for essential errands. The depth of our mobility narrowed to the smartphone: there was a boom in on-demand courier and food delivery services that bridged inhabited spaces.

This special issue was initiated by a symposium organised by the Centre of Visual Arts (CoVA), University of Melbourne and McNally School of Fine Arts, LASALLE College of the Arts of the same name in 2020. Set against the backdrop of the pandemic whereby national borders had closed and the international mobility that the region had become accustomed to suddenly ceased, we had to reconsider what it meant to be part of an archipelago and to encounter through an island geography. Boundaries that were once open, porous and frequently traversed, dissolved. There was no longer an inside and outside in the way described by Glissant, merely land masses that confined our existence and bodies of water that split and demarcated No Man’s Land. Pugh’s island-island relations, which assumed a physical migration of human bodies across islands, were cut. In Melbourne, mobility narrowed to a 5-km radius. The inside and outside of 2020 was the relationship between residential homes, public parks and the grocery store. A similar narrowing happened in the highly built-up Singapore. Residents were asked to stay within their own neighbourhoods and only go out for essential errands. The depth of our mobility narrowed to the smartphone: there was a boom in on-demand courier and food delivery services that bridged inhabited spaces.

Collectively, we experienced the isolation of the newly inaugurated Zoom world, where everyone was their own island decisively split into individual black rectangles. To hold a symposium titled Archipelagic Encounters on Zoom in 2020 was an experiment in island encounters of the digital turn, among people geographically separated by water and socially separated by their respective lockdown conditions.

Archipelagic Encounters is Currents first Special Issue and includes seven submissions that reflect the rich critical and diverse epistemic approaches to regional knowledge that defined the original day of presentations. The archipelagic described the wish or dreams of crossing seemingly insurmountable space, historically this was the oceans and the seas that arbitrarily divided people between island masses. The 2020 symposium and this special issue are an attempt to embody, recuperate and extend this openness between the inhabited and uninhabited spaces in a pandemic world, to be immersed in diverse cultural perspectives and histories. The issue draws together multiple threads that weave through art history, film, music and visual art. Whilst each is representative of a distinct research practice and methodology, there are undercurrents that seep between each contribution that are perhaps broadly endemic to the archipelagic regions of the Asia-Pacific.

A number of the articles and artworks talk of a desire to connect with cultural heritage from the position of a hybrid-self experienced through the diaspora, as researchers generate historic and embodied retracings of the material, aural and linguistic substratum of cultural subjectivity. Conceptually located in the Indian domestic household, Pratibha Nambiar’s practice explores the material and conceptual tensions produced by using spice imbued soap as a mark-making material. Through the use of materials associated with cooking and cleaning, Nambiar’s tools and labour intensive wall drawings make visible the often unseen, ritualistic processes of the domestic sphere—posing questions about the capacity for ritual, trace and the olfactory quality of her materials to imbue these tasks, and the spaces they allude to, with a sense of ownership. Turning to the materiality of language, Kezia Yap retraces her cultural genealogy through a complex process of translating Chinese scripts into music scores as a way to challenge both conventions of Western music production and assumptions about authentic ‘Chineseness’. Yap’s scores pose a new method for music notation as a conceptual process to explore heritage and language to startling effects.

As we have articulated in the introduction thus far there is little escape from the ever pervasive global pandemic as it populates our news feeds, and reorients the way we study, work and socialise. Lizzie Wee’s videos Homecoming and Forced Idleness engage with the all too familiar form of the Zoom conference call.

Archipelagic Encounters is Currents first Special Issue and includes seven submissions that reflect the rich critical and diverse epistemic approaches to regional knowledge that defined the original day of presentations. The archipelagic described the wish or dreams of crossing seemingly insurmountable space, historically this was the oceans and the seas that arbitrarily divided people between island masses. The 2020 symposium and this special issue are an attempt to embody, recuperate and extend this openness between the inhabited and uninhabited spaces in a pandemic world, to be immersed in diverse cultural perspectives and histories. The issue draws together multiple threads that weave through art history, film, music and visual art. Whilst each is representative of a distinct research practice and methodology, there are undercurrents that seep between each contribution that are perhaps broadly endemic to the archipelagic regions of the Asia-Pacific.

A number of the articles and artworks talk of a desire to connect with cultural heritage from the position of a hybrid-self experienced through the diaspora, as researchers generate historic and embodied retracings of the material, aural and linguistic substratum of cultural subjectivity. Conceptually located in the Indian domestic household, Pratibha Nambiar’s practice explores the material and conceptual tensions produced by using spice imbued soap as a mark-making material. Through the use of materials associated with cooking and cleaning, Nambiar’s tools and labour intensive wall drawings make visible the often unseen, ritualistic processes of the domestic sphere—posing questions about the capacity for ritual, trace and the olfactory quality of her materials to imbue these tasks, and the spaces they allude to, with a sense of ownership. Turning to the materiality of language, Kezia Yap retraces her cultural genealogy through a complex process of translating Chinese scripts into music scores as a way to challenge both conventions of Western music production and assumptions about authentic ‘Chineseness’. Yap’s scores pose a new method for music notation as a conceptual process to explore heritage and language to startling effects.

As we have articulated in the introduction thus far there is little escape from the ever pervasive global pandemic as it populates our news feeds, and reorients the way we study, work and socialise. Lizzie Wee’s videos Homecoming and Forced Idleness engage with the all too familiar form of the Zoom conference call.

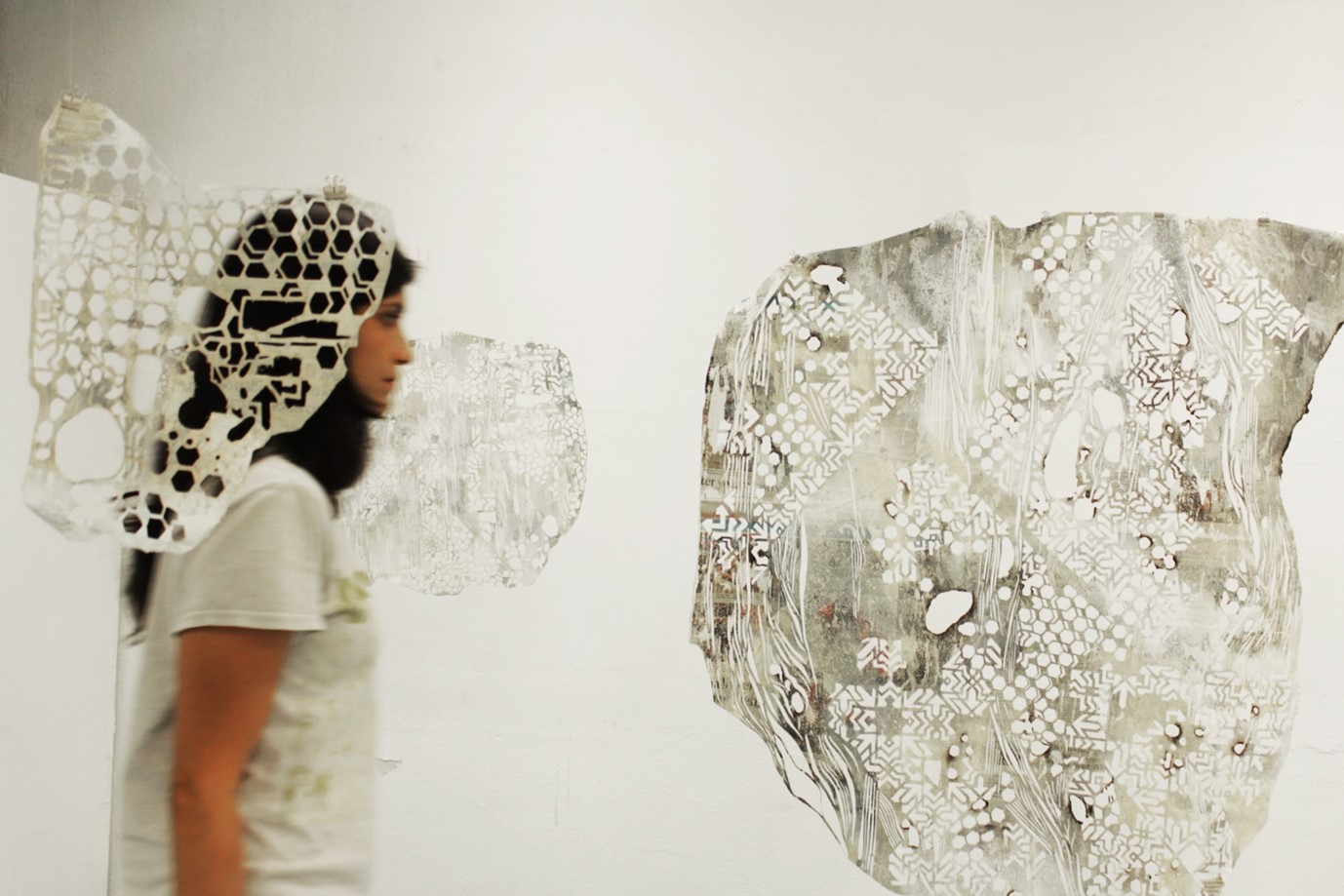

Wee performs a range of characters that she has developed based on broad stereotypes of the ‘Southeast Asian Female’. By mapping archetypes depicted repetitively through television programs, Wee has generated carefully crafted situations that create a mirroring effect between the self and televised cultural expectations. Zoya Chaudhary’s exploration of ‘media as material’ physically demarcates the distance between lived experience and news media in a series of intricate lattice-work pieces based on traditional Jali. The works crafted from newspapers replicate the filtered screens of the Jali, through which the perception of the real and recorded may be filtered or fragmented.

Chaudhary, like Wee, reflects on the impacts of COVID through her project as she describes the emotive negotiation of acts of erasure in relation to news articles of case numbers and death tolls.

The art historical explorations weaving through Archipelagic Encounters take to task overlooked art histories, western conceptions of cinematic spectatorship and the diverse cultural genealogies that have contributed to localised artistic developments in the twentieth century. Nurdiana Rahmat overlays the history of Malay women artists in Singapore connected with the Association of Artists of Various Resources (APAD) with an intersectional feminist framework that locates the artists and works in relation to a network of gendered politics, social dynamics, institutional hierarchies and cultural specificities that previously marginalised or invisibilised them. Genevieve Trail analyses the action and installation work of Choi Yan Chi prior to and in the context of the increased political tensions of Hong Kong in the late twentieth century. By exploring the experimental spatial and installation based works by Chi during the 1980s, Trail develops an important record of a period of Hong Kong’s cultural development that is often eclipsed by the politically charged, identity based work of the 1990s. Contrary to art histories that diminish the complexity and significance of cultural output in the region during this period, Trail’s text seeks to map the trend towards ‘the diffuse and networked uptake of collaborative experimentation’ that Choi’s practice exemplifies. Exploring the contemporary practice of Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s engagement with sleep, cinema and inattention, Duncan Caillard charts the poles of immersion and distraction that pervade his videos and installations. In particular Caillard hones in on Apichatpong’s SLEEPCINEMAHOTEL—a cinematic architecture where spectators could spend the night amidst a constantly streamed projection. Caillard contextualises Apichatpong’s work and the challenges it presents to contemporary cinematic spectatorship by introducing ideas of intimacy, inattention and ‘collective drift’ framed by the act of sleeping.

The artists and historians who have contributed their research to this issue exemplify a desire to form deeper cultural connections through their processes, research methods and materials.

The art historical explorations weaving through Archipelagic Encounters take to task overlooked art histories, western conceptions of cinematic spectatorship and the diverse cultural genealogies that have contributed to localised artistic developments in the twentieth century. Nurdiana Rahmat overlays the history of Malay women artists in Singapore connected with the Association of Artists of Various Resources (APAD) with an intersectional feminist framework that locates the artists and works in relation to a network of gendered politics, social dynamics, institutional hierarchies and cultural specificities that previously marginalised or invisibilised them. Genevieve Trail analyses the action and installation work of Choi Yan Chi prior to and in the context of the increased political tensions of Hong Kong in the late twentieth century. By exploring the experimental spatial and installation based works by Chi during the 1980s, Trail develops an important record of a period of Hong Kong’s cultural development that is often eclipsed by the politically charged, identity based work of the 1990s. Contrary to art histories that diminish the complexity and significance of cultural output in the region during this period, Trail’s text seeks to map the trend towards ‘the diffuse and networked uptake of collaborative experimentation’ that Choi’s practice exemplifies. Exploring the contemporary practice of Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s engagement with sleep, cinema and inattention, Duncan Caillard charts the poles of immersion and distraction that pervade his videos and installations. In particular Caillard hones in on Apichatpong’s SLEEPCINEMAHOTEL—a cinematic architecture where spectators could spend the night amidst a constantly streamed projection. Caillard contextualises Apichatpong’s work and the challenges it presents to contemporary cinematic spectatorship by introducing ideas of intimacy, inattention and ‘collective drift’ framed by the act of sleeping.

The artists and historians who have contributed their research to this issue exemplify a desire to form deeper cultural connections through their processes, research methods and materials.

Their powerful, ongoing contributions to regional discourse highlights the value of arts capacity to strengthen cultural ties and broaden our understanding of who we are. Drawn together, we hope Archipelagic Encounters captures the diverse relations that come to the fore as we move through and within the plural histories, heritage and cultural positions that network between the island-to-island relations of the archipelago.

These connections have been, to borrow from Trail’s observations on Choi’s practice in Hong Kong, an attempt to hold on to the insistently diffused mode of collaborative work between island-selves that have appeared and disappeared from the horizons over the past two years. Working together through this period on Archipelagic Encounters has been a way to find some footing, connecting researchers through their distinct practices.

We deeply thank all of the contributors for their startling level of commitment over this time, we thank the reviewers for their thoughts, encouragement and critical engagement with the submissions and finally we hope you the reader will encounter new knowledge, research approaches or overlooked histories that will connect you to the interrelated cultural multiplicities of our region.

Acknowledgements:Archieplagic Encounters has been supported by the School of Culture and Communications, University of Melbourne.

We would like to acknowledge the organising partners of the Archipelagic Encounters symposium: Elyssia Bugg, PhD Candidate (Art History) & Centre of Visual Arts Graduate Fellow, University of Melbourne, Australia. Dr. Danny Butt, Associate Director (Research), Victorian College of the Arts, University of Melbourne, Australia. Dr. S Chandrasekaran, Head, McNally School of Fine Arts, LASALLE College of the Arts, Singapore. Chloe Ho, PhD Candidate (Art History) & Centre of Visual Arts Graduate Fellow, University of Melbourne, Australia. Adeline Kueh, Senior Lecturer, MA Fine Arts, LASALLE College of the Arts, Singapore. Jeffrey Say, Programme Leader, MA Asian Art Histories LASALLE College of the Arts, Singapore. Ian Woo, Programme Leader, MA Fine Arts, LASALLE College of the Arts, Singapore. Clare Veal, Lecturer, MA Asian Art Histories, LASALLE College of the Arts, Singapore

Presenters at the Archipelagic Encounters Symposium:

Chelsea Coon, Chloe Ho, Chris Parkinson, Duncan Caillard, Elyssia Bugg, Erman Ashburn, Genevieve Trail, Kellie Wells, Kezia Yap, Krystina Lyon, Laurence Marvin Castillo, Lizzie Wee, Manu Sharma, Nurdiana Rahmat, Pratibha Nambiar, Shinjita Roy, Tianyue Wang, Victoria Hertel and Zoya Chaudhary.

We also like to acknowledge the contributions of the Centre of Visual Art, University of Melbourne in particular Vice Chancellor Su Baker Dr Suzie Fraser and Eleanor Simcoe. We would also like to thank the staff of McNally School of Fine Arts, LASALLE College of the Arts, Singapore.

Notes:

1. Pugh, Jonathan. ‘Island Movements: Thinking with the Archipelago’. Island Studies Journal. 8. 9-24. (2013). p. 10

2. Ibid. p. 13

3. Glissant, É. (1989) Caribbean discourse: selected essays. M. Dash (Trans.). Charlottesville: Caraf. P. 139

We deeply thank all of the contributors for their startling level of commitment over this time, we thank the reviewers for their thoughts, encouragement and critical engagement with the submissions and finally we hope you the reader will encounter new knowledge, research approaches or overlooked histories that will connect you to the interrelated cultural multiplicities of our region.

Acknowledgements:Archieplagic Encounters has been supported by the School of Culture and Communications, University of Melbourne.

We would like to acknowledge the organising partners of the Archipelagic Encounters symposium: Elyssia Bugg, PhD Candidate (Art History) & Centre of Visual Arts Graduate Fellow, University of Melbourne, Australia. Dr. Danny Butt, Associate Director (Research), Victorian College of the Arts, University of Melbourne, Australia. Dr. S Chandrasekaran, Head, McNally School of Fine Arts, LASALLE College of the Arts, Singapore. Chloe Ho, PhD Candidate (Art History) & Centre of Visual Arts Graduate Fellow, University of Melbourne, Australia. Adeline Kueh, Senior Lecturer, MA Fine Arts, LASALLE College of the Arts, Singapore. Jeffrey Say, Programme Leader, MA Asian Art Histories LASALLE College of the Arts, Singapore. Ian Woo, Programme Leader, MA Fine Arts, LASALLE College of the Arts, Singapore. Clare Veal, Lecturer, MA Asian Art Histories, LASALLE College of the Arts, Singapore

Presenters at the Archipelagic Encounters Symposium:

Chelsea Coon, Chloe Ho, Chris Parkinson, Duncan Caillard, Elyssia Bugg, Erman Ashburn, Genevieve Trail, Kellie Wells, Kezia Yap, Krystina Lyon, Laurence Marvin Castillo, Lizzie Wee, Manu Sharma, Nurdiana Rahmat, Pratibha Nambiar, Shinjita Roy, Tianyue Wang, Victoria Hertel and Zoya Chaudhary.

We also like to acknowledge the contributions of the Centre of Visual Art, University of Melbourne in particular Vice Chancellor Su Baker Dr Suzie Fraser and Eleanor Simcoe. We would also like to thank the staff of McNally School of Fine Arts, LASALLE College of the Arts, Singapore.

Notes:

1. Pugh, Jonathan. ‘Island Movements: Thinking with the Archipelago’. Island Studies Journal. 8. 9-24. (2013). p. 10

2. Ibid. p. 13

3. Glissant, É. (1989) Caribbean discourse: selected essays. M. Dash (Trans.). Charlottesville: Caraf. P. 139

About the editors:

Elyssia Bugg Elyssia Bugg is a PhD candidate in Art History at the University of Melbourne. Her research focuses on theories of performativity as they relate to early sculptural works from the Arte Povera movement. She is also the co-organiser of the inaugural Archipelagic Encounters Symposium, with LASALLE College of the Arts, Singapore, and is a member of the Centre of Visual Art Graduate Academy in Melbourne.

Jeremy Eaton is an artist and writer based in Narrm/Melbourne. He is the editorial coordinator of the Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art and a board member of un Magazine. Jeremy has exhibited throughout Australia participating in exhibitions at Sarah Scout Presents, Dominik Mersch Gallery, West Space, BUS Projects, CAVES, Margaret Lawrence Gallery and the Centre for Contemporary Photography. Jeremy has also written extensively for artists, galleries and publications including: the Ian Potter Museum of Art, Art + Australia, un Projects and Gertrude Contemporary.

Chloe Ho is a doctoral candidate in Art History at the University of Melbourne. Her interest is in twentieth and twenty-first century Singapore art, specifically in relation to performance and installation art and art historiography. She investigates the place of performance in the transmission of art and the art historical in the Singapore context, looking at artistic works, social phenomena and its relation to society. Her current research project attempts to account for the transmission of art critical and art historical knowledge in the Singapore context outside Western structures of knowledge with a special focus on the late 1980s to the present. More broadly, Chloe is interested in performance art forms in the Asian context, Southeast Asian art histories and artistic migration, particularly in relation to performance art and artists.

Elyssia Bugg Elyssia Bugg is a PhD candidate in Art History at the University of Melbourne. Her research focuses on theories of performativity as they relate to early sculptural works from the Arte Povera movement. She is also the co-organiser of the inaugural Archipelagic Encounters Symposium, with LASALLE College of the Arts, Singapore, and is a member of the Centre of Visual Art Graduate Academy in Melbourne.

Jeremy Eaton is an artist and writer based in Narrm/Melbourne. He is the editorial coordinator of the Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art and a board member of un Magazine. Jeremy has exhibited throughout Australia participating in exhibitions at Sarah Scout Presents, Dominik Mersch Gallery, West Space, BUS Projects, CAVES, Margaret Lawrence Gallery and the Centre for Contemporary Photography. Jeremy has also written extensively for artists, galleries and publications including: the Ian Potter Museum of Art, Art + Australia, un Projects and Gertrude Contemporary.

Chloe Ho is a doctoral candidate in Art History at the University of Melbourne. Her interest is in twentieth and twenty-first century Singapore art, specifically in relation to performance and installation art and art historiography. She investigates the place of performance in the transmission of art and the art historical in the Singapore context, looking at artistic works, social phenomena and its relation to society. Her current research project attempts to account for the transmission of art critical and art historical knowledge in the Singapore context outside Western structures of knowledge with a special focus on the late 1980s to the present. More broadly, Chloe is interested in performance art forms in the Asian context, Southeast Asian art histories and artistic migration, particularly in relation to performance art and artists.

Shaping Perception: Negotiating media as material, the fragility of time and fleeting emotions

Zoya Chaudhary

To cite this contribution: Chaudhary, Zoya. ‘Shaping Perception: Negotiating media as material, the fragility of time and fleeting emotions’. Currents Journal, Archipelagic Encounters (2021), https://currentsjournal.net/Shaping-Perception.

Download this article ︎︎︎PDF

Keywords: Jali, materiality, media, erasure, newspaper

Abstract:The essay, artwork and process imagery presented here, features hand cut-out newspaper works from my (Zoya Chaudhary) series Fragments & Echo that draw inspiration from Indo-Persian latticed Jali. The series negotiates news media reportage and materiality as a testament to the fragility of time, space and fleeting emotional responses. By cutting, burning and scratching patterned motifs into the surface of newspapers from particular dates, I explore the notion of ‘media as material’. This is to consider news media as a referent to past events that are under erasure in their representational form, drawing attention to their materiality.

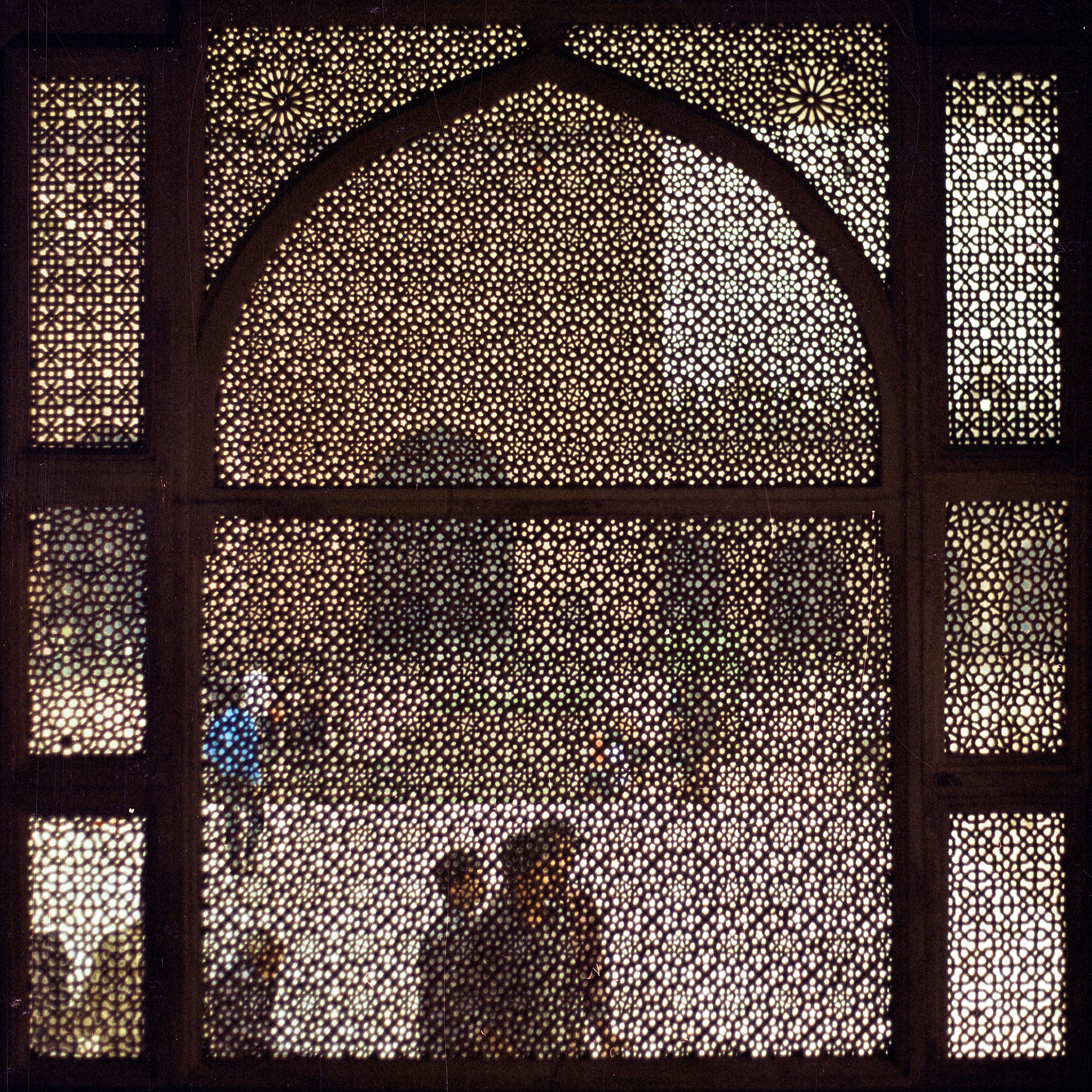

[Figure 1] Reference image of Jali marble carved windows from Fatehpur Sikri, India. https://www.flickr.com/photos/doctorcasino/7809341254/. Accessed 26th September 2021. Courtesy Addison Godel.

The dull white The Straits Times newspaper from May 15, 2021 that I had glued onto a thin canvas sheet had darkened and wrinkled in some places. I scratched and sanded the newspaper surface to even it out. I cut patterns by following lines I had previously traced on the glued newspaper. ‘Rare fungal infection hits COVID-19 patients in India’—a line I had read and cutover, kept ringing in my head alongside an image of two men, one of them unmasked, carrying another man into a rural looking clinic. I can not remember if the image was from the same article or was from another article on the same page, yet the image and text are vaguely connected in my memory. Residing in Singapore, I have not been able to visit my home country, India, since January 2020. My 92-year-old grandfather had just recovered from the COVID-19 virus and was back home from hospital, thankfully, I thought. But the lingering dread around the implications of the new ‘black fungus’ infection stayed. At least it stayed until the sound of water coming to full boil in the water heater distracted my thoughts. Sipping my coffee, I was back to rhythmic cutting, calm again as I cut, cut, and cut. At the corner where I had cut out a shape, a tiny little piece of the newspaper peeled out. Images, thoughts, and surrounding sounds seemed to have merged, forming a blur in my head.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Images

^^^

From

March18..., 2020, series ‘Fragments’ as displayed at Lasalle

Winstedt studio space, Singapore. Image

of the series ‘Echo’, as displayed at Lasalle Winstedt studio space, Singapore, 2020.

Close-up of overlapping surfaces

from the series Echo, 2020

Images

^^^

From

March18..., 2020, series ‘Fragments’ as displayed at Lasalle

Winstedt studio space, Singapore. Image

of the series ‘Echo’, as displayed at Lasalle Winstedt studio space, Singapore, 2020.

Close-up of overlapping surfaces

from the series Echo, 2020

Media in its various formats is perhaps the most ubiquitous and powerful force that is shaping perception and memory in current times. My practice-based research is focused on the formation of subjectivity and perception in relation to the information gleaned from media. Especially how subjective filters of perception are created from the cultural, physical, and temporal vantage point affected by notions of erasure. In this essay, I will discuss works from my series Fragments & Echo, works that I started making from March 2020 onwards. I was then in the first semester of my Master of Fine Arts degree at LASALLE College of Arts, Singapore, which also coincided with the break-out of the pandemic. In the following text, I will first discuss the cut-out mesh-like surfaces that I create and the historical and cultural significance of the Jali [Figure 1] inspired patterns in my works. I will then expand on the use of media, specifically the daily newspaper—as a representational form that communicates events on the one hand and the materiality of its surface on the other. I hope to be able to draw connections between the fragility of the material outcome of the works, which is a testament to the fragile interrelations of time, space, and fleeting emotions. Burning

The cut-out surfaces

I view my works from the series Fragments & Echo presented here as one of the many layers of filters that holds a trace or fragmented memories of a time and space. The traces of newsprint on the cut-out patterned surfaces in Fragments & Echo suggests a residual fragmented memory comprised of lost information and a perceptual shift between media and material. Formally these cut-out surfaces seek to open a space for the viewer to explore their own perceptual awareness of unique spatial and temporal conditions. Cut-out surfaces in my works act like filters of perception. The porosity of the surfaces is tied to John Berger’s idea evoked above, speaking to the enormous ‘gap’ between the narrative being offered to us through various apparatus, such as newspapers, and our experience of an internal ever-changing subjectivity. Each individual has built-in psychological filters that we use to focus or block out external information that are perceived and received in diverse ways. Exploring my personal filters, I drew inspiration from Jali patterns to cut-out geometric shapes that have a cultural significance for me.

Jali as a personal frame

Indo-Persian latticed Jali screens, an architectural feature, are patterned carvings of stone railings and screens that are found in older homes, temples, mosques, and monuments across the Indian subcontinent. The word Jali meaning ‘an iron net’ in Urdu and Sanskrit is employed to describe pierced screens.2 Historically, in Asia and the Mediterranean where the sun rays can be very strong, master artisans evolved this aesthetic language of light. In India, these perforated screens have been traced back to the mid-sixth century Chalukyan period.3 The carved-out lattice patterns on stone and other material shaped and filtered light into enclosed spaces lending a luminescent softness and providing a cooling effect. The Islamic influence brought in complex patterns built on tessellation, a simple geometric progression of a single form that was representative of the infinite nature of the divine. Living in Singapore, away from my home country, the Jali patterned surfaces conceptually and materially act as a cultural framing device. Personally, for me, these walls are nostalgic and remind me of places and experiences of my childhood. The craft of Jali within the Indian sub-continent can be traced to an origin that combines Hindu craftsmen’s indigenous skills with Islamic geometric designs.4 The lineage of Jali designs is pertinent to my relationship with the Jali and why I use it as a reference in my practice, as I come from a mixed Hindu and Muslim parentage. This unique cultural union, which is rare between people, even in present-day India due to religious polarisation, is visible in the architecture, food, poetry, and many other aspects of Indian cultural heritage including the Jali, hence making it a strong starting point for me.

![]() Image

^^^

Close up images of the making of From April10..., 2020, series ‘Fragments’.

Image

^^^

Close up images of the making of From April10..., 2020, series ‘Fragments’.

Media as a material trace

In this accompanying text, I will discuss the notion of ‘media as a material’ and how this idea functions within my series Fragments & Echo. My practice to date has led me to look at news media as a referent to past events but also how it has been materially presented. Jacques Derrida's writings on language as a ‘trace’ informed my way of looking at media as a material trace. Derrida refers to the trace as a ‘still-living mark on the substrate, a surface, a place of origin’.5 By referring to language as ‘trace’ instead of a sign, Derrida acknowledges the limitation of the written ‘word’, suggesting that it is neither present nor absent. Charles Merewether in his essay Fact Remains uses Derrida’s notion of ‘trace’ and applies it to photographic and video representations of events. He questions the acceptance of such representation as material evidence and calls it ‘trace’ to critique its dependability. Merewether explains,

This aspect, of a trace being neither past nor present, is particularly relevant to the subject of media information that is presented as truth. Merewether further argues that ‘[i]n allowing us to look back, the trace offers a connection to the world insofar as it operates as a memorial form tied to the past but, forever threatened by forgetfulness and erasure.’7

Media in its various formats is perhaps the most ubiquitous and powerful force that is shaping perception and memory in current times. My practice-based research is focused on the formation of subjectivity and perception in relation to the information gleaned from media. Especially how subjective filters of perception are created from the cultural, physical, and temporal vantage point affected by notions of erasure. In this essay, I will discuss works from my series Fragments & Echo, works that I started making from March 2020 onwards. I was then in the first semester of my Master of Fine Arts degree at LASALLE College of Arts, Singapore, which also coincided with the break-out of the pandemic. In the following text, I will first discuss the cut-out mesh-like surfaces that I create and the historical and cultural significance of the Jali [Figure 1] inspired patterns in my works. I will then expand on the use of media, specifically the daily newspaper—as a representational form that communicates events on the one hand and the materiality of its surface on the other. I hope to be able to draw connections between the fragility of the material outcome of the works, which is a testament to the fragile interrelations of time, space, and fleeting emotions. Burning

The cut-out surfaces

Between the experience of living a normal life at this moment on the planet and the public narratives being offered to give a sense of that life, the empty space, the gap, is enormous.1

-John Berger

I view my works from the series Fragments & Echo presented here as one of the many layers of filters that holds a trace or fragmented memories of a time and space. The traces of newsprint on the cut-out patterned surfaces in Fragments & Echo suggests a residual fragmented memory comprised of lost information and a perceptual shift between media and material. Formally these cut-out surfaces seek to open a space for the viewer to explore their own perceptual awareness of unique spatial and temporal conditions. Cut-out surfaces in my works act like filters of perception. The porosity of the surfaces is tied to John Berger’s idea evoked above, speaking to the enormous ‘gap’ between the narrative being offered to us through various apparatus, such as newspapers, and our experience of an internal ever-changing subjectivity. Each individual has built-in psychological filters that we use to focus or block out external information that are perceived and received in diverse ways. Exploring my personal filters, I drew inspiration from Jali patterns to cut-out geometric shapes that have a cultural significance for me.

Jali as a personal frame

Indo-Persian latticed Jali screens, an architectural feature, are patterned carvings of stone railings and screens that are found in older homes, temples, mosques, and monuments across the Indian subcontinent. The word Jali meaning ‘an iron net’ in Urdu and Sanskrit is employed to describe pierced screens.2 Historically, in Asia and the Mediterranean where the sun rays can be very strong, master artisans evolved this aesthetic language of light. In India, these perforated screens have been traced back to the mid-sixth century Chalukyan period.3 The carved-out lattice patterns on stone and other material shaped and filtered light into enclosed spaces lending a luminescent softness and providing a cooling effect. The Islamic influence brought in complex patterns built on tessellation, a simple geometric progression of a single form that was representative of the infinite nature of the divine. Living in Singapore, away from my home country, the Jali patterned surfaces conceptually and materially act as a cultural framing device. Personally, for me, these walls are nostalgic and remind me of places and experiences of my childhood. The craft of Jali within the Indian sub-continent can be traced to an origin that combines Hindu craftsmen’s indigenous skills with Islamic geometric designs.4 The lineage of Jali designs is pertinent to my relationship with the Jali and why I use it as a reference in my practice, as I come from a mixed Hindu and Muslim parentage. This unique cultural union, which is rare between people, even in present-day India due to religious polarisation, is visible in the architecture, food, poetry, and many other aspects of Indian cultural heritage including the Jali, hence making it a strong starting point for me.

Image

^^^

Close up images of the making of From April10..., 2020, series ‘Fragments’.

Image

^^^

Close up images of the making of From April10..., 2020, series ‘Fragments’.Media as a material trace

In this accompanying text, I will discuss the notion of ‘media as a material’ and how this idea functions within my series Fragments & Echo. My practice to date has led me to look at news media as a referent to past events but also how it has been materially presented. Jacques Derrida's writings on language as a ‘trace’ informed my way of looking at media as a material trace. Derrida refers to the trace as a ‘still-living mark on the substrate, a surface, a place of origin’.5 By referring to language as ‘trace’ instead of a sign, Derrida acknowledges the limitation of the written ‘word’, suggesting that it is neither present nor absent. Charles Merewether in his essay Fact Remains uses Derrida’s notion of ‘trace’ and applies it to photographic and video representations of events. He questions the acceptance of such representation as material evidence and calls it ‘trace’ to critique its dependability. Merewether explains,

‘… to view the event in such terms (material evidence) is to suggest that a material memory or trace to do with the past survives in the present, a materiality that can be identified. Is the trace therefore something residual: a remainder that survives, like a fragment? Or is the trace alternatively, something less, insofar as its appearance is not a matter of survival but, rather more like the hollowed-out imprint of an impression: a past that has never been present?’6

This aspect, of a trace being neither past nor present, is particularly relevant to the subject of media information that is presented as truth. Merewether further argues that ‘[i]n allowing us to look back, the trace offers a connection to the world insofar as it operates as a memorial form tied to the past but, forever threatened by forgetfulness and erasure.’7

This vulnerable presence of the trace of news media in material form is

very powerful to me since it directly critiques the idea of truth. In these

works, I aim to create a tension caused by the presence of the newspaper referring to the conditions of time in residual remains on the one hand, and the delicately cut-out material, on the other. How a news article, a representation of an event in the form of pictures

and words is materially presented relates directly to their social, economic,

political discourse and how it’s received and handled relates to the personal. The text, made unreadable or incoherent, suggests a

'distance', which could refer to the disappearance or fading away of the trauma

of news events. The tools and

actions that I have chosen to use to interact with the ‘media-material’ become

important, as they reflect my underlying motivations, intentions, and emotional

reactions to the particularities of the media material. I take the media material

and with the help of either physical or digital tools, edit the material by

scratching, cutting, burning, erasing, or blurring almost wrestling with it to transform

it into something delicate and almost beautiful.

Fragments & Echo

In the series of works called Fragments & Echo, I started with gluing sheets of newsprint paper on canvas. I then indeterminately scratched out portions of the surface. I had been occupied with the idea of filters (both perceptual and conceptual) and the correlation with screens as a type of filter or viewing device. The idea of the artwork taking on the characteristics of a filter seemed exciting. I started using repetitive shapes forming Jali-inspired patterns to cut-out sections from a sheet of newspaper stuck to a thin canvas, transforming into a mesh-like form. During this process I was trying to better understand the subjective filters I apply when viewing the mediated public narrative that is given to us through media. I thought about the juxtaposition of the rhythmic patterns of my presence, my breath, my daily routines with the media information I was working with. To visually present this feeling I traced a combination of two or three existing Jali pattern designs from architectural Jali drawings. Combining repetitive patterns, some determinate, some indeterminate, I would cut over the traced lines on the surface. The neatness of the cut-out forms varied with the state of mind I was in. By cutting the geometric forms and burning holes with incense sticks and a kitchen lighter, I transformed the surface into a mesh-like form. I started work on the first Jali work From March 18… from the series Fragments & Echo, around the time Singapore was in its lockdown due to the onset of the global COVID-19 pandemic. The local newspaper at that point was filled with virus-related news that depicted the anxiety and panic that could be felt across the globe. Taking newsprint paper from a single day, I used household tools to create a surface with suggestions of the news but transformed it into something that was not very definitive and open to interpretation. While cutting out patterns, I would get carried away by the repetitive actions, at times forgetting what I was cutting. The forms, images, and text became abstract material that I was shaping. But at other times I would stop and read or re-read the news article and take in the information. Sometimes, I would avoid cutting out an immigrant child's face, at other times I would want to cut-out a certain news piece with a statistical chart of a certain country’s virus death toll, rendering it invisible. News about jobless migrant workers from poor neighbouring countries desperate to get out of Thailand out of fear of the closing borders; news highlighting the rough conditions of the migrant workers working in Singapore in packed dormitories where cases were on a rise—were just some of the anxiety and dismay laden news that was collectively encountered on a daily or hourly basis. I saw my actions of erasure by cutting that I used over the news pieces as a coping mechanism. The final works only had a suggestion of the news articles or imagery. Each piece of the Jali cut-out work was named after the day, for example, From April 10th…, since it felt like a memorial for that particular day.

![]()

![]() Images

^^^

From

May15..., 2021, from the series ‘Echo’. Acrylic

paint, found newsprint paper on canvas 115 x 76 cm

Images

^^^

From

May15..., 2021, from the series ‘Echo’. Acrylic

paint, found newsprint paper on canvas 115 x 76 cm

These works could be seen as palimpsestic overwriting, yet I would say there is a fundamental difference between that process and using erasure as an artistic tool. I see my actions and erasure of sections of news media as its own powerplay employing reductive methods as an act of philosophical exigency. It could also be seen as unearthing new modes of framing, voicing, and thinking about a subject. The writers of historical manuscripts (palimpsests) were hardly ever bothered about the content of the text that had disappeared over time or had been consciously erased by them. This is rarely the case with an artist who paints over a word or a writer who cancels words on printed pages, or a collective that savagely annotates some objectionable document. It mattered to Robert Rauschenberg that it was a de Kooning drawing he was trying to erase (Erased de Kooning Drawing, 1953), just as it mattered to Marcel Broodthaer that he was blacking out Mallarmé’s famous poem (Un coup de dés jamais n'abolira le hasard (A throw of the dice will never abolish chance, 1969). In the same way, Derrida’s placement of a cross mark on a fundamental term of metaphysics was intentional.8 Similarly, in my cut-out surfaces of Fragments & Echo , by acknowledging the used news articles date, as the title of the works, the altered material presence of the news trace in my cut-out surfaces from the series seeks to open up new modes of thinking about that day, its trace and the gaps that are formed between media and perception.

Notes:

1. Berger, John. “A Man with Tousled Hair”, The Shape of a Pocket. Vintage international, 2003.

2. Abbas, Masooma. “Ornamental Jālīs of the Mughals and Their Precursors” International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 6, No. 3; March 2016

3. Smith (n.d.) the lattices at Belur are twenty-eight in number derived from the Early Chalukyan Style of Southern India; See Tadgell (1990, pp. 137-138) plates 98, 100b, 122 and 158c for lattices of pre-Islamic Hindu period.

4. Abbas, Masooma. “Ornamental Jālīs of the Mughals and Their Precursors” International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 6, No. 3; March 2016

5. Derrida, Jacques. Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, 97

6. Merewether, Charles. “The Fact Remains”. In ISSUE 08: Erase. Singapore: Lasalle College of the Arts, 2019. pp.51-52

7. Merewether, Charles. “The Fact Remains”. In ISSUE 08: Erase. Singapore: Lasalle College of the Arts, 2019. pp.51-52

8. Rubinstein, Raphael. “Missing: erasure | Must include: erasure”, Under Erasure website, 2018. Pierogi Gallery, https://www.under-erasure.com/essay-by-raphael-rubinstein/. Accessed 6th December 2020

About the contributor:

Zoya Chaudhary is an artist born in India and a resident of Singapore for the last nine years. Working across mediums including installation, video, cut-out collage & painting, Chaudhary’s practice focuses on perception and its fragmentation in today’s media informed world. She is interested in the idea of the origins of information being filtered through various apparatus as it passes through the ever-changing reality of human subjectivity. Her works begin with the personal, and then build to consider ways the personal interacts with larger public narrative.

Chaudhary graduated with MA in Fine Arts from LASALLE College of the Arts in partnership with Goldsmiths, University of London in 2021. She has worked as a graphic artist, illustrator and designer in India and Singapore, before she started a dedicated art practice in 2016. Since her parents were from a theatre background she spent her formative years watching, performing and designing for several theatre productions. Chaudhary has been invited to show her art in several group exhibitions and art fairs in Singapore and the Netherlands since 2012. Her first solo exhibition Lost and Found-Singapore was held in August 2018 at Utterly Art Gallery, Singapore. Her painting Thinking Tamil, Talking Singlish, Eating Chinese received the Art Gemini Award, 2019. Website: https://zoyachaudhary.com Instagram: @zoyachaudhary_studio

Fragments & Echo

In the series of works called Fragments & Echo, I started with gluing sheets of newsprint paper on canvas. I then indeterminately scratched out portions of the surface. I had been occupied with the idea of filters (both perceptual and conceptual) and the correlation with screens as a type of filter or viewing device. The idea of the artwork taking on the characteristics of a filter seemed exciting. I started using repetitive shapes forming Jali-inspired patterns to cut-out sections from a sheet of newspaper stuck to a thin canvas, transforming into a mesh-like form. During this process I was trying to better understand the subjective filters I apply when viewing the mediated public narrative that is given to us through media. I thought about the juxtaposition of the rhythmic patterns of my presence, my breath, my daily routines with the media information I was working with. To visually present this feeling I traced a combination of two or three existing Jali pattern designs from architectural Jali drawings. Combining repetitive patterns, some determinate, some indeterminate, I would cut over the traced lines on the surface. The neatness of the cut-out forms varied with the state of mind I was in. By cutting the geometric forms and burning holes with incense sticks and a kitchen lighter, I transformed the surface into a mesh-like form. I started work on the first Jali work From March 18… from the series Fragments & Echo, around the time Singapore was in its lockdown due to the onset of the global COVID-19 pandemic. The local newspaper at that point was filled with virus-related news that depicted the anxiety and panic that could be felt across the globe. Taking newsprint paper from a single day, I used household tools to create a surface with suggestions of the news but transformed it into something that was not very definitive and open to interpretation. While cutting out patterns, I would get carried away by the repetitive actions, at times forgetting what I was cutting. The forms, images, and text became abstract material that I was shaping. But at other times I would stop and read or re-read the news article and take in the information. Sometimes, I would avoid cutting out an immigrant child's face, at other times I would want to cut-out a certain news piece with a statistical chart of a certain country’s virus death toll, rendering it invisible. News about jobless migrant workers from poor neighbouring countries desperate to get out of Thailand out of fear of the closing borders; news highlighting the rough conditions of the migrant workers working in Singapore in packed dormitories where cases were on a rise—were just some of the anxiety and dismay laden news that was collectively encountered on a daily or hourly basis. I saw my actions of erasure by cutting that I used over the news pieces as a coping mechanism. The final works only had a suggestion of the news articles or imagery. Each piece of the Jali cut-out work was named after the day, for example, From April 10th…, since it felt like a memorial for that particular day.

These works could be seen as palimpsestic overwriting, yet I would say there is a fundamental difference between that process and using erasure as an artistic tool. I see my actions and erasure of sections of news media as its own powerplay employing reductive methods as an act of philosophical exigency. It could also be seen as unearthing new modes of framing, voicing, and thinking about a subject. The writers of historical manuscripts (palimpsests) were hardly ever bothered about the content of the text that had disappeared over time or had been consciously erased by them. This is rarely the case with an artist who paints over a word or a writer who cancels words on printed pages, or a collective that savagely annotates some objectionable document. It mattered to Robert Rauschenberg that it was a de Kooning drawing he was trying to erase (Erased de Kooning Drawing, 1953), just as it mattered to Marcel Broodthaer that he was blacking out Mallarmé’s famous poem (Un coup de dés jamais n'abolira le hasard (A throw of the dice will never abolish chance, 1969). In the same way, Derrida’s placement of a cross mark on a fundamental term of metaphysics was intentional.8 Similarly, in my cut-out surfaces of Fragments & Echo , by acknowledging the used news articles date, as the title of the works, the altered material presence of the news trace in my cut-out surfaces from the series seeks to open up new modes of thinking about that day, its trace and the gaps that are formed between media and perception.

Notes:

1. Berger, John. “A Man with Tousled Hair”, The Shape of a Pocket. Vintage international, 2003.

2. Abbas, Masooma. “Ornamental Jālīs of the Mughals and Their Precursors” International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 6, No. 3; March 2016

3. Smith (n.d.) the lattices at Belur are twenty-eight in number derived from the Early Chalukyan Style of Southern India; See Tadgell (1990, pp. 137-138) plates 98, 100b, 122 and 158c for lattices of pre-Islamic Hindu period.

4. Abbas, Masooma. “Ornamental Jālīs of the Mughals and Their Precursors” International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 6, No. 3; March 2016

5. Derrida, Jacques. Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, 97

6. Merewether, Charles. “The Fact Remains”. In ISSUE 08: Erase. Singapore: Lasalle College of the Arts, 2019. pp.51-52

7. Merewether, Charles. “The Fact Remains”. In ISSUE 08: Erase. Singapore: Lasalle College of the Arts, 2019. pp.51-52

8. Rubinstein, Raphael. “Missing: erasure | Must include: erasure”, Under Erasure website, 2018. Pierogi Gallery, https://www.under-erasure.com/essay-by-raphael-rubinstein/. Accessed 6th December 2020

About the contributor:

Zoya Chaudhary is an artist born in India and a resident of Singapore for the last nine years. Working across mediums including installation, video, cut-out collage & painting, Chaudhary’s practice focuses on perception and its fragmentation in today’s media informed world. She is interested in the idea of the origins of information being filtered through various apparatus as it passes through the ever-changing reality of human subjectivity. Her works begin with the personal, and then build to consider ways the personal interacts with larger public narrative.

Chaudhary graduated with MA in Fine Arts from LASALLE College of the Arts in partnership with Goldsmiths, University of London in 2021. She has worked as a graphic artist, illustrator and designer in India and Singapore, before she started a dedicated art practice in 2016. Since her parents were from a theatre background she spent her formative years watching, performing and designing for several theatre productions. Chaudhary has been invited to show her art in several group exhibitions and art fairs in Singapore and the Netherlands since 2012. Her first solo exhibition Lost and Found-Singapore was held in August 2018 at Utterly Art Gallery, Singapore. Her painting Thinking Tamil, Talking Singlish, Eating Chinese received the Art Gemini Award, 2019. Website: https://zoyachaudhary.com Instagram: @zoyachaudhary_studio

Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Sleep Cinema: Intimacy, Inattention, Surrealism

Duncan Caillard

To cite this contribution: Caillard, Duncan. ‘Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Sleep Cinema: Intimacy, Inattention, Surrealism’. Currents Journal, Archipelagic Encounters (2021), https://currentsjournal.net/Apichatpong-Weerasethakuls-Sleep-Cinema.

Download this article ︎︎︎PDF

Keywords:

Sleep; experimental cinema; Surrealism; art cinema; spectatorship; installation art; Apichatpong Weerasethakul; Andy Warhol; André Breton; Jean-Luc Nancy; Thai Cinema

Abstract:

This article investigates the role of sleep in Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s filmmaking. Throughout his career, Apichatpong has exhibited an idiosyncratic interest in sleep. In contrast to conventional narrative cinema, his narrative features typically follow associational dream logics, his characters are often shown sleeping or in states of partial consciousness, while the slow, purposeful rhythms of his film style often lull spectators to sleep. Yet beyond sleeps diegetic appearance in his films, it also informs Apichatpong’s unusual understanding of the architecture of cinematic spectatorship, guiding his belief that sleep and cinema are inextricably entwined. Within this article, I analyse Apichatpong’s installation SLEEPCINEMAHOTEL, a fusion of video installation with functioning hotel first staged at the International Film Festival Rotterdam in 2018, which I situate within the broader aesthetic traditions of surrealism, durational performance and contemporary Thai cinema, concentrating on the work of André Breton, Andy Warhol, Max Richter and Thai animistic cinema. Through this analysis, I argue that Apichatpong’s cinematic mediation of sleep marks a significant departure from conventional organisations of cinema, and creates space for inattentiveness, intimacy and political action among spectators.

[Figure 1] Apichatpong Weerasethakul, SLEEPCINEMAHOTEL, 2018, video installation and hotel, International Film Festival Rotterdam. Photo: Duncan Caillard

In January 2018, Apichatpong

Weerasethakul mounted his first SLEEPCINEMAHOTEL, a fusion of immersive video

installation with a functioning overnight hotel.1 Staged in an upper floor conference space at the Postillon Convention Centre in

downtown Rotterdam, the SLEEPCINEMAHOTEL allowed paying guests to stay

overnight in a communal sleeping space accompanied by a single-channel video

projection and a curated soundscape of running water and rustling leaves. Guests

were free to come and go at any time, and other festival attendees were invited

to watch from a viewing area positioned above the sleeping platforms,

allowing them to watch both the video projection and the sleeping bodies

beneath them.

SLEEPCINEMAHOTEL spatialised Apichatpong’s ongoing fascination with sleep, dreaming and inattention. A range of his feature films idiosyncratically included long takes of characters sleeping, opposing conventional narrative cinema’s focus on active, goal-oriented protagonists. Sleeping bodies recurred throughout Apichatpong’s narrative films, which devoted unusually long amounts of time to characters drifting between various states of consciousness. His second feature film, Blissfully Yours (2002), ended with a four-minute shot of one of his characters falling asleep, while the plot of Cemetery of Splendour (2015) circulated around a group of Thai soldiers paralysed by a mysterious sleeping sickness, depicting the soldiers bodies at rest in a hall filled with hypnotic shifting lights. Apichatpong’s fascination with sleep was even more pronounced in his short film and video installation work. In his short film Morakot (Emerald) (2007), the camera floated through an abandoned Bangkok hotel, looking out onto empty, unmade beds as a visual reminder of Thai urban decay. His silent, three-channel installation TEEM (2007) showed his then-boyfriend Chaisiri Jiwarangsan waking up in the morning—restaging Andy Warhol’s Sleep (1963)—while other exhibitions from Primitive (2009) to For Tomorrow and For Tonight (2011) included footage of sleeping bodies arranged throughout the gallery space.

Yet Apichatpong’s fascination with sleep extended beyond the diegetic contents of his film works and into his very understanding of the architecture of cinematic attention. He had often noted his comfort with spectators sleeping through his lethargic, dream-like feature films, stating in 2011 that ‘I am fine when people say that they fall asleep in my movies. They wake up and can patch things together in their own way.’2 He reiterated this disinterest in disciplined forms of spectatorship in 2018, stating his desire ‘to have a cinema specifically for sleeping. I feel because, for me, over the years I have become less and less interested in watching movies. Even [in] my own films, I sleep.’3

For Apichatpong, sleep and dreaming were indistinguishable from cinematic experience itself. He stated, ‘I always believe that we possess the best cinema. We don’t need other cinema, meaning that when we sleep, it’s our own image, our own experience that we edit at night and process.’4 By collapsing ontological distinctions between the collective experience of cinema and the personal experience of dreaming, Apichatpong proposed a cinema that was both a cinema of sleep (within which sleep is represented), and a cinema that was sleep (in which sleep was intimately and inextricably involved in the spectatorial process).

In this article, I investigate the issue of sleep within Apichatpong’s cinema and explore its implications for his reimagined architecture of cinematic attention. This analysis is derived from fieldwork completed in 2018 at the International Film Festival Rotterdam (IFFR) and incorporates elements of my own embodied experiences within the space. My focus here is not on a representational analysis of sleep within his filmmaking, but rather centres on sleep as an embodied spectatorial condition in-itself, a style of viewing in which the sleeping body of the spectator is not only permitted but encouraged by the film style itself. As Apichatpong’s work constantly strayed between feature film, short film and installation, at times integrating multiple artistic conventions in the process, my analysis is intentionally cross-media and interdisciplinary, and addresses the structural similarities between his modes of practice. By addressing the interdisciplinary yet structural resonances in Apichatpong’s practice, I argue that his relaxed and idiosyncratic understanding of spectatorship substantially reshaped our understanding of film experience and opened up new avenues for interpersonal intimacy and political resistance.

![]() [Figure

2] The projection screen at the front of the SLEEPCINEMAHOTEL,

(Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2018) video installation and hotel, International

Film Festival Rotterdam. Photo: Duncan Caillard

[Figure

2] The projection screen at the front of the SLEEPCINEMAHOTEL,

(Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2018) video installation and hotel, International

Film Festival Rotterdam. Photo: Duncan Caillard

Practicing Sleep Cinema: SLEEPCINEMAHOTEL

Apichatpong’s SLEEPCINEMAHOTEL was an outworking of Apichatpong’s long-term relationship with the International Film Festival Rotterdam, and was open to the public over five days in the January 2018 edition of the festival. Staged in a conference space on an upper floor of Rotterdam’s Postillon Convention Centre, the SLEEPCINEMAHOTEL cost between €75 and €150 per night. Guests stayed in a communal sleeping space segmented into individual ‘sleeping pods’ that were made from mesh screening and semi-transparent privacy curtains suspended by a grid of metal scaffolding at varying heights from the floor. From one of the rooms, a large window—which was covered at night by thick stage curtains that blocked out external light—looked out onto the city street a few levels below. A large, double-sided circular screen suspended by wires between the window and the sleeping structure was visible from both inside the installation space and from the street outside [figure 1]. A viewing platform was positioned on an upper floor on the opposite side of the room with seating freely available to hotel guests and the general public. A private bar and a set of temporary showers were installed in a foyer outside the main screening space, where a communal breakfast was served in the morning.

A video was continuously projected throughout the duration of the installation, with a short break between 2:00pm and 4:00pm each day to clean and reset the space for the next night’s guests. In contrast to Apichatpong’s usual work (which prior to 2018 was almost exclusively shot and set in Thailand), the footage projected onto the screen was sourced from the Dutch EYE Filmmuseum and the Netherlands Institute of Sound and Vision, featuring archival footage of boats, water, clouds, sleeping people and sleeping animals.5 There was no discernible narrative or signifying logic between the pieces of archival footage, which were edited through a process of association, cutting between shots of clocks, boats on rivers, churches in the European countryside and sleeping animals without any immediately obvious links between the sequence of images. This video projection was paired with a looped soundscape of wind, rustling leaves and ocean waves prepared by Apichatpong’s regular sound designer, Akritchalerm Kalayanamitr, reflecting the mood and contents of the found footage on screen. In concert, these sounds and images created a soothing spectatorial environment, and, as there was no evident logic governing the montage on-screen, spectators could fall asleep at any time without missing relevant information. Instead of demarcating narrative progression, the footage on-screen paired with the soundscape to create a frictionless space in which attention was optional and the spectatorial experience was not contingent on the actual contents on-screen.

Furthermore, the structure of the sleeping pods visually interfered with the spectators view of the screen [figure 2]. The sleeping pods were rudimentary: each platform contained a bed, side table and lamp, with a single geometric structure comprised of scaffolding that supported the pods at the centre of the room. Rather than face the same direction, the beds were positioned at a 45-degree angle to the screen, with views obscured by other parts of the structure. This meant that guests had a perpetually disrupted view of the screen. In addition to this structural obscurity, the walls of the installation space were made from a polished wood that curved as it connected with the double-height roof made from the same finish, resembling the interior inverted hull of a ship. The effect at night, when the screen became the dominant light source in the room, cast distorted reflections across the polished surfaces of the walls and roof that were visible from the beds. Although a small viewing space was set up at the front of the room with bean bags to allow guests to watch the screens directly, the primary form of participant engagement with the screen was from their beds via the indirect light of the reflections.

SLEEPCINEMAHOTEL played with transitions and permeable divisions between interior and exterior space. Guests were free to come and go at their leisure, meaning that there was regular traffic between the screening space, the bar area and the outside world. Although each bed was propped up on its own platform, the absence of walls and the thin metal struts of the scaffolding created a permeable boundary between each sleeping pod and other spectators in the rest of the space. Even while sleeping with privacy curtains, sleepers were always visible to others from an observation deck on a mezzanine, from which members of the public could attend the installation between 4:00pm and 10:00pm each day.

As the scaffolding intentionally obstructed my view of the screen from my bed, I found myself looking around the space at the other sleepers, listening as they whispered to one another. For visitors on the mezzanine level above, the scaffolding structure partially blocked their view of the screen, directing their attention down towards the metal structure and reclining bodies contained within it. Expanding the layers of observation of SLEEPCINEMAHOTEL, the circular screen was double sided and positioned in front of the window, meaning that the images were constantly visible to passers-by outside. These carefully orchestrated conditions exposed overnight guests from all directions: to the light of the projections, the looks of their fellow guests, the spectatorship of visitors in the upper level, and the attentions of pedestrians on the street.

I regard three features of Apichatpong’s sleep cinema to be particularly significant. First, by de-centring the screen within the space and implementing circumstances that allowed spectators to drift in and out of the space, and between states of consciousness and unconsciousness, Apichatpong decentred the spectating subject within his sleep cinema. This open structure and ‘drift’ contrasted with the conventional organisation of mono-directional spectatorship in Western cinema. Second, the SLEEPCINEMAHOTEL was arranged in such a way that guests were repeatedly exposed to other guests and viewers within the installation, producing a state of heightened vulnerability and intimacy between them. Whereas conventional cinema directed attention away from other spectators toward the screen, Apichatpong’s sleep cinema encouraged guests to spectate on each other. Finally, by using seemingly arbitrary footage and allowing spectators to make free associations between them, Apichatpong’s sleep cinema created a space of epistemic freedom for spectators, surrealistically opening them to new, disordered organisations of meaning in which they freely associated between the imagery, reflections and experiences within the space. Together, Apichatpong’s cinematic divergences radically reorganised the conventional architecture of cinematic attention and established new forms of spectatorial participation.

Inattentive Cinemas

Upon checking into the SLEEPCINEMAHOTEL, guests were provided a selection of hotel accoutrements: a towel, single use soaps and shampoos, bottled water, a bar menu and, interestingly, a blindfold. Although the inclusion of the blindfold was seemingly unremarkable given the hotel setting, it also signalled SLEEPCINEMAHOTEL’s opposition to the conventional structure of cinematic attention and subjectivity. Rather than demand constant attention, Apichatpong’s sleep cinema asked its guests to look away. By giving guests the means to block visual perception—an experience ordinarily at the heart of cinema itself—Apichatpong’s sleep cinema decentred active, attentive subjects within its apparatus and replaced them with a partial and distracted spectator, free to come and go at their own leisure. By relaxing the conventional demands of viewing by allowing spectators to drift between consciousness and unconsciousness, presence and absence, SLEEPCINEMAHOTEL modelled a form of cinema in which human subjects were either decentred or absent, and within which the spectator’s apprehension of the work will always be incomplete.

Over the past several decades, numerous artists associated with contemporary arts, performing arts and cinema have experimented with spectatorial attention through excessive duration. In 1963, John Cage staged a complete rendition of Erik Satie’s Vexations,a musical work organised around a short theme that was repeated 840 times in succession. The performance lasted from 6:00pm to 12:40pm the following day and was performed by twelve pianists, who rotated throughout the night.6 In his description of the event, Justin Remes noted that spectators came and went freely throughout the performance, or engaged in other activities such as ‘eating, drinking, whispering, reading, writing, and sleeping.’7 In 2015, composer Max Richter performed his eight-and-a-half-hour piece Sleep for the first time live over BBC Radio 3, a performance he has since restaged to overnight audiences across the world. Composed in conversation with neuroscientific research, Richter’s Sleep was designed to create the ideal auditory conditions for its listeners to sleep, through slow pacing, rhythmic repetitions and low auditory frequencies. Richter’s performance inverted the conventional organisation of attention within Western art music, turning away from disciplined expectations of attention toward more relaxed and sensuous forms of spectatorial participation.

In its unprecedented experimentation with duration, Warhol’s Sleep (1963) initiated a movement of extreme durational filmmaking and launched an aesthetic fascination with sleeping bodies. As Adam Sitney argued in his history of American experimental filmmaking, Warhol ‘was the first film-maker to try to make films which would outlast a viewer’s initial state of perception’, producing a work completely incompatible with the hyperattentive conditions of contemporary spectatorship.8 For Sitney, Warhol’s Sleep’s slow pace and absence of visual action served as a profound reorienting purpose for spectators and allowed ‘the persistent viewer [to] alter his experience before the sameness of the cinematic image.’9

We can see similar structural resemblances between SLEEPCINEMAHOTEL and Christian Marclay’s The Clock (2010), a 24-hour montage of clocks appropriated from film history edited together to present the clock-time of the place in which it was exhibited (for example, an on-screen clock will read 11:46 at 11:46pm). Like SLEEPCINEMAHOTEL, The Clock’s excessive runtime exceeded the attention spans of its spectators and could never be full appreciated in one sitting. Unlike The Clock, which presented a play of recognition for attentive spectators that Julie Levinson described as both ‘a riveting game of “name that movie”’ for cinephiles, the images of SLEEPCINEMAHOTEL was not organised with any obvious narrative, formal or logical connections between them and as such did not offer the same pleasures for cinephiles, encouraging instead a relaxed indifference to the contents on-screen.10

We can further situate the inattentive form of spectatorship of sleep cinema within the histories of Thai cinema, which decentralised the position of the disciplined spectating subject within the cinematic apparatus. Apichatpong’s filmmaking was intimately entangled with this Thai cinematic tradition alongside animistic traditions of the Isaan region in northeast Thailand—with apparitions, reincarnations and monstrous spirits serving as key motifs across his oeuvre. Also, Apichatpong’s relationship with animism inflected the spatial and spectatorial conditions of his films.11 Within northeast Thailand, there was a practice of conducting film projections as offerings to spirits at local shrines, which in contrast to commercial cinemas that charge for (human) admission, were paid for by petitioners as part of a transaction with local spirits in return for supernatural intervention in personal problems (such as help conceiving a child, assistance with an exam, or winning lottery numbers).12 As Richard Lowell MacDonald observed, ‘the film show is itself a medium of exchange and ritual action… a vehicle through which a ritual transaction is conducted with a powerful supernatural being linked to a specific sacred place where the screening occurring.’ As a result the sponsor of each screening rarely requested specific screenings and they frequently do not attend them in person.13 Rather, these screenings were exhibited primarily ‘for’ spirits. Human spectators were decentred as the viewing subjects within the apparatus of Thai animistic cinema. MacDonald further observed that the human spectators of these screenings were usually itinerant workers found on the street at night—motorcycle taxi drivers, hawkers, laborers and the homeless—who would only stay for part of the screening.14 These screenings were commonplace in Isaan and often took place at a shrine adjacent to Khon Kaen University (Apichatpong’s alma mater), placing this comfortably within his sphere of experience.

Similar to these animistic screenings, Apichatpong’s SLEEPCINEMAHOTEL structurally decentred spectating subjects, making it impossible for them to apprehend the entirety of the projected video work. The video projection was non-repeating and featured 120 hours of archival footage such that no two moments within SLEEPCINEMAHOTEL were identical. Echoing Nancy’s metaphor of a boat gently leaving its moorings, marketing material for the installation emphasised the impossibility of fully experiencing the video, stating that ‘[j]ust like one can never step into the same river twice, any instant in the SLEEPCINEMAHOTEL [was] as unique as it [was] ephemeral.’15